OTKHODNICHESTVO – temporary departure of peasants from their places of residence to work in the cities and for agricultural work in other areas. In Russia it has become widespread since the end. 17th century due to the strengthening of the feudal lords. exploitation and increasing the role of money. . It was also noted earlier among the quitrent peasants (burlachestvo, cabbies), and among the Chuvash. peasants have been known since the middle. 18th century (work at copper and iron ore enterprises in the Urals). In the 1st half. 19th century expanded due to ship and barge work. Significant became widespread after the abolition of fortress. rights. In 1897–98 in Alatyr., Buin., Kurmysh., Kozmodemyan., Tetyush., Civil., Cheboksary., Yadrin. In the districts there were, respectively, 4022, 1622, 29, 2064, 975, 1639, 1365, 2213 otkhodniks, which accounted for 8.1% of the working-age men. population of these counties. The main directions of O. were the Urals and Siberia (factories and mines), Simbir., Samar. province (agricultural work), as well as the construction of railways. roads (Kazan-Ryazan, Ural, etc.), enterprises of Kazan and Nizhny Novgorod, Baku oil fields, Donbass mines, salt and fishing. crafts of Astrakhan. Chuvash, who did not speak Russian. language, they were more often hired by the Tatars. Earnings ranged from 30–40 rubles. per season up to 150 rubles. in year. The development of O. contributed to the spread of literacy and knowledge of Russian. language, broadened the horizons of peasants, contributed to the introduction of commodity money. relations in Chuvash. village, increased the standard of living and changed the peasants. everyday life

O. acquired a massive scale during the period of industrialization of the country and collectivization of villages. farms. On June 30, 1931, the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR adopted a resolution “On otkhodnichestvo,” which provided benefits to peasants who left under industrial contracts. construction. In 1933–34, in order to strengthen collective and state farms, a number of decrees were issued prohibiting unauthorized farming. In the post-war period. O. period gradually developed into mass migration of villages. population (especially young people) to cities. After 1965, when enterprises were given the opportunity to create wage funds. boards, the so-called covening. Due to the high density of villages. population, seasonality of labor and relatively low earnings, collective farmers of Chuvashia went to work in the cereals. cities and the Lower Volga region (collecting tomatoes, watermelons, sunflowers). Collective farms hired brigades of “shabashniks” to build farms and other villages. structures. O. in this form the official. authorities regarded it as negative. phenomenon (resolution of the Council of Ministers of the USSR of June 19, 1973 “On regulating the labor of collective farmers for seasonal work”). In the end 20 – beginning 21st centuries times care. from places of residence to work in other areas acquired a significant amount. scale.

The roads of peasants who temporarily left their native village to earn money on the side crossed Russia in all directions.

They went to close, long and very long distances, from north to south and from west to east. They left to return on time, and brought from foreign places not only money or purchased things, but many impressions, new knowledge and observations, new approaches to life. The village of Suganovo, Kaluga district, is the central part of European Russia, what is called indigenous Rus'. At the end of the 19th century, people left it to earn money in Moscow, Odessa, Nikolaev, Ekaterinoslavl and other cities. Mostly young men, even teenagers, before military service, went on retreat here. It is a rare man in this village who has not gone to work. Sometimes girls also left: as nannies, cooks in the workers' artels of fellow countrymen. But in other places, women's work was generally frowned upon. Here is information from the same time from the Dorogobuzh district of the Smolensk region. Mostly young guys, but also soldiers returning from service, also go to work here. “Almost everyone” engaged in withdrawal on their own accord. This “almost” apparently refers to those cases when the guy was sent to work by his family or by the highway. The deceased certainly sends money to the family. Women, with rare exceptions, never go to work.

And the volosts adjacent to Onega “are distinguished by their skillful and fearless navigators.” If the farm of a peasant family was small and there were more workers in the family than needed, then the “extra” were spent on everyday earnings for a long time, sometimes even three years, leaving the family. But most otkhodniks left their families and households only for that part of the year when there was no field work. In the central region, the most common period of otkhodnichestvo was from the Filippov ritual (November 14/27) to the Annunciation (March 25/April 7). The period was counted according to these milestones, since they were permanent (they did not belong to the movable part of the church calendar). In some seasonal jobs, such as construction, the hiring deadlines could be different. Waste trades were very different - both in types of occupations and in their social essence. A peasant otkhodnik could be a temporary hired worker in a factory or a farm laborer on the farm of a wealthy peasant, or he could also be an independent artisan, contractor, or Gorgov worker. Okhodnichestvo reached a particularly large scale in the Moscow, Vladimir, Tver, Yaroslavl, Kostroma and Kaluga provinces. In them, leaving to earn money outside was already widespread in the last quarter of the 18th century and further increased.

For the entire central region, the main place of attraction for otkhodniks was Moscow. Before the reform, the predominant part of otkhodniks in the central industrial region were landowner peasants. This circumstance deserves special attention when clarifying the possibilities for the interests and real activities of the serf peasant to go beyond the boundaries of his volost. Those who like to speculate about the passivity and attachment to one place of the majority of the population of pre-revolutionary Russia do not seem to notice this phenomenon. The Vladimir province has long been famous for the skills of carpenters and masons, stonemasons and plasterers, roofers and painters. In the 50s of the 19th century, 30 thousand carpenters and 15 thousand masons went to Moscow from this province to work. We went to Belokamennaya in large teams. Usually the head of the artel (contractor) became a peasant “more prosperous and resourceful” than others. He himself selected members of the artel from 165 fellow villagers or residents of nearby villages. Some peasant artel workers took on large contracts in Moscow and assembled artels of several hundred people. Such large artels of builders were divided into parts, under the supervision of foremen, who, in turn, eventually became contractors.

Among the specialties for which the Vladimir peasants on retreat were famous, the peculiar occupation of the ofeni occupied a prominent place. Ofeni are traders of small goods peddling or delivering. They served mainly villages and small towns. They traded mainly in books, icons, paper, popular prints in combination with silk, needles, earrings, rings, etc. Among the Ofeni, their “Ofenian language” had long been in use, in which peddlers of goods spoke among themselves during trade. Otkhodnichestvo for the Ofensky fishery was especially widespread in the Kovrovsky and Vyaznikovsky districts of the Vladimir province. In a description received by the Geographical Society in 1866 from the Vyaznikovsky district, it was reported that many peasants from large families from Uspenye (August 15/28) set off with ophens. They usually “left” for one winter. Others left “even young wives.” By November 21 (December 4), many of them were in a hurry to get to the Vvedenskaya Fair in the Kholui settlement. Vyaznikovsky ofeni went with goods to the “lower” provinces (that is, along the lower Volga), Little Russia (Ukraine) and Siberia. At the end of Lent, many ofeni returned home “with gifts to the family and money as rent.” After Easter, everyone returned from the Ofen fishery and took part in agricultural work. Ofeni-Vyaznikovites were also known outside of Russia. A source from the mid-18th century reported that they had long “traveled with holy icons to distant countries” - to Poland, Greece, “to Slavenia, the Serbs, the Bulgarians” and other places. In the 80s of the 19th century, the people of the Vladimir province bought images in Mstera and Kholuy and sent them in convoys to fairs “from Eastern Siberia to Turkey.”

At the same time, in remote places they accepted orders for the next delivery. The scale of the trade in Vladimir icons in Bulgaria in the last quarter of the 19th century is evidenced by the following curious fact. In the village of Goryachevo (Vladimir province), which specialized in the manufacture of various types of carriages, the Ofeni ordered in the spring of 1881 120 carts of a special design, specially adapted for transporting icons. The carts were intended to transport Palekh, Kholuy and Mstera icons throughout Bulgaria. The Yaroslavl peasants showed great ingenuity in making money in Moscow. They became, in particular, the initiators of setting up vegetable gardens in the wastelands of a big city. The fact is that the Yaroslavl province had rich experience in the development of vegetable gardening. The peasantry of the Rostov district was especially famous in this regard. At the end of the 18th - beginning of the 19th centuries, Rostov peasants already had many vegetable gardens in Moscow and its environs. Only according to annual passports, about 7,000 peasants left the Yaroslavl province in 1853 for gardening. 90 percent of them went to Moscow and St. Petersburg. Ogorodniks (like other otkhodniks) varied greatly in the nature and size of their income. Some Rostov peasants had their own vegetable gardens in Moscow on purchased or leased land. Others were hired as workers by their fellow villagers. Thus, in the 30-50s of the 19th century, in the Sushchevskaya and Basmannaya parts of Moscow, as well as in the Tverskaya-Yamskaya Sloboda, there were extensive vegetable gardens of rich peasants from the village of Porechye, Rostov district.

They made extensive use of hiring their fellow countrymen. Renting out plots to peasant gardeners brought significant income to Moscow land owners. If they were landowners, they sometimes rented out their Moscow land for vegetable gardens to their own serfs. S. M. Golitsyn, for example, rented a large plot of land from his Yaroslavl serf Fyodor Gusev. Often the tenant, in turn, subleased such a plot in small parts to fellow villagers. Yaroslavl peasants in Moscow were engaged in more than just gardening. Frequent among them were also the professions of peddler, shopkeeper, hairdresser, tailor, and especially innkeeper. “The innkeeper is not a Yaroslavl resident - a strange phenomenon, a suspicious creature,” pisa; I. T. Kokorev about Moscow in the forties of the last century. The specialization in waste industries of entire regions or individual villages was noticeably influenced by their geographical location. Thus, in the Ryazan province, in villages close to the Oka, the main latrine industry was barge hauling. Along the Oka and Prona rivers they were also engaged in grain trade. Wealthier peasants participated in the supply of grain to merchants, and poorer peasants, as small trusted merchants (shmyrei), bought small reserves of grain from small landowners and peasants.

Others made money from the carriage industry associated with the grain trade: they delivered grain to the pier. Others worked on the piers, stuffing sculls, loading and unloading ships. In the steppe part of the Ryazan province, the latrine fishery of shertobits successfully developed. Traditions of professional skills have developed here on the basis of local sheep breeding. Sherstobits went to the Don, to the Stavropol region, to Rostov, Novocherkassk and other steppe places. Most of the Sherstobits were in the villages of Durnoy, Semensk, Pronskiye Sloboda, Pecherniki, Troitsky, Fedorovsky and neighboring villages. To beat wool and felt buroks, they went south on carts. Some Sherstobites left their native places for a year, but the majority went to the steppe places only after the grain harvest and until the next spring. In the wooded areas of the same Ryazan region, crafts related to wood prevailed.

However, their specific type depended on the local tradition, which created its own techniques, its own school of skill. Thus, a number of villages in Spassky district specialized in cooperage. The peasants practiced it locally and used their passports to travel to the southern, wine-growing regions of Russia, where their skills were in great demand. The main center of the cooperage industry in Spassky district was the village of Izhevskoye. Izhevsk residents prepared part of the material for making barrels at home. As soon as the river opened up, they loaded large boats with this material in whole batches and sailed to Kazan. In Kazan, the main preparation of cooperage boards took place, after which the Ryazan coopers moved south. In the Yegoryevsky district of the Ryazan province, many villages specialized in the manufacture of wooden reeds, combs and spindles. Reed is an accessory of a weaving machine, a type of comb. Yegoryevites sold berds in rural markets of Ryazan, Vladimir and Moscow provinces. Their main sales were in the southern regions - the Don Army Region and the Caucasus, as well as in the Urals. They were delivered there by buyers from Yegoryevsk peasants, who from generation to generation specialized in this type of trade. In the minds of the residents of the Don and the Caucasus, the occupation of berd-shchik was firmly associated with origins from Yegoryevsk. Bird buyers took goods from their neighbors on credit and sent them on carts to the steppe regions.

About two and a half thousand reeds, spindles and combs were transported on one cart. In places where goods were exported, in villages and other villages, Yegoryevsk peasants had acquaintances and even friends. These relationships were often inherited. Southerners eagerly awaited distant guests at certain times - with their goods, gifts and news stories. Confidence in a friendly welcome, free maintenance from friends, free grazing for tired horses - all this encouraged Yegoryev peasants to maintain this type of otkhodnichestvo. They returned with a significant profit. The lifestyle of peasant otkhodniks in big cities developed its own traditions. This was facilitated by a certain cohesion between them, 167 associated with leaving the same places, and specialization in this type of income on the side. For example, some villages of the Yukhnovsky district of the Smolensk province regularly supplied water carriers to Moscow. In Moscow, Smolensk peasants who came to fish would unite in groups of 10 or even 30 people.

They jointly rented an apartment and a hostess (matka), who prepared food for them and looked after order in the house in the absence of water carriers. Let us note in passing that in the past, the service of large cities by village residents who came there for a while and returned home to their families superficially resembles the same “shuttle” method of work in rural areas that other economists are now thinking about. In part, it is now being implemented not very successfully in temporary “deployments” or collective trips of townspeople to the field. And then he walked in the opposite direction. The majority of the country's population lived in healthy rural conditions. Part of the rural population “shuttle” provided labor for industry (almost all types of industry used the labor of otkhodniks) and, if we use the modern term, the service sector: cab drivers, water carriers, maids, nannies, clerks, innkeepers, shoemakers, tailors, etc. To this should be added , that many of the landowners lived and served in the city temporarily, then returned to their estates.

Contemporaries assessed the significance of otkhodnichestvo in peasant life differently. They often noted the spirit of self-sufficiency and independence among those who worked on the side, especially in big cities, and emphasized the knowledge of otkhodniks in a wide variety of issues. For example, folklorist P. I. Yakushkin, who visited the villages a lot, wrote in the 40s of the 19th century about the Rannenburg district of the Ryazan province: “The people in the district are more educated than in other places, the reason for which is clear - many go to work from here to Moscow, to the Niz (that is, to the districts in the lower reaches of the Volga - M.G.), they are recruiting like crazy.” But many - in articles, private correspondence, responses from the field to the programs of the Geographical Society and the Ethnographic Bureau of Prince Tenishev - expressed concern about the damage to morality that the waste caused. There is no doubt that traveling to new places, working in different conditions and often living in a different environment - all this expanded the peasant’s horizons, enriched him with fresh impressions and diverse knowledge. He got the opportunity to directly see and understand much in the life of cities or rural areas remote and different from his native places. What was known by hearsay became reality. Geographical and social concepts developed, communication took place with a wide range of people who shared their opinions. I. S. Aksakov, driving through the Tambov province in 1844, wrote to his parents: “On the road we came across a coachman who had been to Astrakhan and drove there as a cab. He praised this province very much, calling it popular and cheerful, because there are many tribes there and in the summer men flock from everywhere to fish.

I am amazed how a Russian person bravely goes on a long-distance fishing trip to places that are completely alien, and then returns to his homeland as if nothing had happened.” But the other side of otkhodnichestvo is also quite obvious: families left behind for a long time, the bachelor lifestyle of the deceased, sometimes superficial borrowing of urban culture to the detriment of traditional moral principles instilled by upbringing in the village. I. S. Aksakov, in another letter from the same trip, will write about the Astrakhan otkhodnichestvo from the words of a coachman from a neighboring province: “Whoever goes to Astrakhan once becomes completely different, forgets everything about the house and joins an artel consisting of 50, 100 or more people.

The artel has everything in common; approaching the city, she hangs out her badges, and the merchants rush to open their gates to them; your own language, your own songs and jokes. For such a person, the family disappears...”168 Nevertheless, the peasant “leaven” for many turned out to be stronger than superficial negative influences. The preservation of good traditions was also facilitated by the fact that during the retreat, peasants, as a rule, stuck to their fellow countrymen - due to artelism in work and life, mutual support in certain professions. If the otkhodnik acted not in an artel, but individually, he still usually settled with fellow villagers who had moved completely to the city, but maintained close ties with their relatives in the village.

The public opinion of the peasant environment retained its strength here to a certain extent. Along the roads of settlers and otkhodniks, pilgrims and walkers with petitions, buyers and traders, coachmen and soldiers, the Russian peasant walked and traveled through his great Fatherland. With passionate interest, he listened at home to news about what was happening in Rus', talked about them and argued with his fellow villagers. At a community meeting, he decided how best to apply the old and new laws to his peasant affairs. He knew a lot about the past of Russia, composed songs about it, and kept legends. The memory of the exploits of his ancestors was as personal and simple to him as the instructions of his fathers about the courage of a warrior. The peasant was also aware of his place in the life of the Fatherland - his duty and role as a plowman and breadwinner. “A man has a bag, he has a loaf of bread, he has everything,” an old peasant from the Amginskaya settlement in Eastern Siberia told the historian A.P. Shchapov in the 70s of the last century. “The bread is his money, his tea is sugar. A man is a worker, his work is his capital, his purpose from God.”

Shchapov also recorded the statement of another peasant from the Podpruginsky village on the same topic: “Men are not merchants, but peasants, arable workers: they don’t have to accumulate capital, but to generate the income necessary for the house, for the family, and for good labors to be verbally honored in the world, in society." Respect for one’s work as a plowman and awareness of oneself as part of a large community of peasants in general, men in general, for which this occupation is the main one, was often accompanied by a direct assessment of the role of this activity in the life of the state and the Fatherland.

This happened, in particular, in the introductory part of petitions. Before proceeding to present a specific request, the peasants wrote about the importance of agricultural labor in general. Thus, the peasants of the Biryusinsky volost of the Nizhneudinsky district wrote in 1840 in a petition addressed to the inspector of state property: “Peasants by nature are destined to have a direct occupation with agriculture; arable farming, although it requires a lot of tireless work and vigilant care, but in the most innocent way rewards the peasant farmer for his efforts a satisfied reward with fertility, to this the vigilant authorities repeatedly gave encouragement and compulsion with their instructions, which continue to this day in the Highest Will.”

Waste, waste trades, otkhodnik - concepts that were outdated by the first third of the 20th century have again become relevant in our days. At the end of the Soviet period of Russian history, where such a phenomenon could not exist in principle, otkhodnichestvo reappeared in the country as a special form of labor migration. The new form, having some differences, has important similarities with the one that existed a century ago, which forced researchers to return to the previous, already forgotten name “otkhodnichestvo”.

Otkhodnichestvo is an amazing phenomenon of our social and economic life. It is surprising primarily for its invisibility. Not only ordinary people do not know about otkhodnichestvo and otkhodniks; neither the authorities nor scientists know about them. Meanwhile, this is a mass phenomenon. According to the most approximate and conservative estimates, out of approximately 50 million Russian families, at least 10-15, and perhaps all 20 million families live on the work of one or both adult members. In other words, a considerable share of the country’s GDP is provided by otkhodniks, but is not taken into account by statistics and cannot be taken into account, because otkhodniks as a market subject do not exist for economic science.

But for the authorities they do not exist and as an object of social policy. Otkhodniks are outside politics: as an object of management, they do not exist not only for state authorities, but also for local authorities, which know nothing about them. But they are the very residents for whose sake the municipal government implements one of those three well-known and worthy sciences of management, about which the official M. E. Saltykov once wrote.

Otkhodniks do not exist for sociological science either: we do not know who they are, what kind of life they lead, what they eat, what they breathe and what they dream about. We don’t know what the families of otkhodniks are like, how the socialization of children in them proceeds, how they differ from the families of their non-otkhodnik neighbors.

What is this - new otkhodnichestvo in Russia? Why did it suddenly - as if from scratch - be revived in modern Russia?

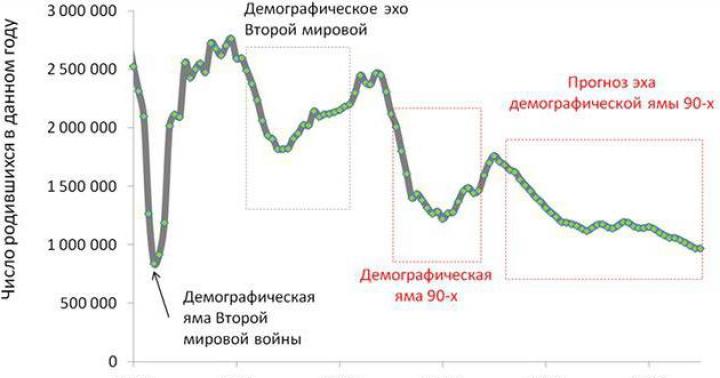

Otkhodnichestvo arose again as a new mass phenomenon of socio-economic life in the mid-90s of the 20th century. In the early 1990s, as a response to the economic disorder in the country, “ways of life” began to quickly emerge - new models of life support for the population, forced to independently search for means of survival. In addition to the creation of new models (such as “shuttles”, however, quite similar to the “bagmen” of the 20s), long-forgotten ones were “remembered” and revived, the first of which was a return to subsistence farming and the revival of waste industries. In the early 90s, I specifically became concerned with the issue of identifying and describing the various models of life support that the country’s population was forced to turn to with the beginning of “shock therapy” of the economy. To my surprise at the time, in the new circumstances, the provincial population en masse began to turn not to modern models of economic behavior (such as “shuttle trades” or “registration for unemployment” - not for the sake of a meager benefit, but solely for the purpose of maintaining seniority for the sake of a future pension) , but to models that have long disappeared, forgotten, “archaic”. This turned out to be, on the one hand, subsistence farming, widespread for entire villages and cities, and on the other hand, the revival of waste industries as a model of life support, additional to subsistence production. Moreover, this new otkhodnichestvo began not from its historical center, from non-black earth regions, but from the outskirts, from the former Soviet republics, to the center. Only after some time did this centripetal movement also capture the areas closest to it, which had once been the main areas of withdrawal. Perhaps this is why the population of not only the areas of traditional “old otkhodnichestvo”, but also almost all post-Soviet republics, as well as the eastern Siberian territories of Russia, is now involved in latrine trades, which has never happened before.

Otkhodnichestvo, a phenomenon widespread among the peasantry of imperial Russia in the 18th, 19th and first third of the 20th centuries, had characteristic features that made it possible to classify it as a special form of labor migration of the population. Otkhodnichestvo was understood as seasonal return movements of peasants, mostly men, from their places of permanent residence and farming to other settlements and provinces in order to seek additional income through various crafts (handicrafts) or hiring, offering their services on the side. Otkhodnichestvo was a very large-scale phenomenon. By the end of the 19th century, from half to three quarters of the entire male peasant population of the non-black earth central and northern provinces went to work in neighboring and distant regions and provinces every season (usually winter), reaching the very outskirts of the empire.

Otkhodnichestvo as a model of economic behavior can only develop if two obligatory conditions are present: the prerequisite is the relative or complete consolidation of a person and his family on the land, and the driving force behind otkhodnichestvo is the impossibility of feeding on the spot, forcing one to look for third-party sources of livelihood. It was impossible to feed oneself in the densely populated poor non-chernozem territories in central and northern Russia by the 18th century. However, the population, attached to the land for life by the state, community or landowner, could not leave their place of residence without a good reason. Presumably, the state itself gave the first strong impetus to the population to develop latrine industries, which definitely existed in the 16th-17th centuries, with the massive forced movement of peasants at the beginning of the 18th century to Peter’s “great construction projects” (St. Petersburg and many other new cities) and to the great wars (recruitment set) . The rural community also more easily begins to send individual of its craftsmen to the cities to earn money, which allows it to more easily pay government taxes. By the beginning of the 19th century, landowners, realizing that quitrent was more profitable than corvée, were releasing an increasing number of serfs to work in the trades every year, and, moreover, were facilitating their training in crafts. This is how otkhodnichestvo gradually develops, capturing the central and northern provinces of the Russian Empire. From the middle of the 19th century, an even more rapid development of otkhodnichestvo began, first stimulated by the permission of landowners to mortgage their estates, then by the emancipation of 1861, and by the 1890s by the industrial boom, as well as overpopulation. The latter occurred to a large extent due to agricultural underdevelopment, caused by resistance to innovation on the part of the peasant community and the disinterest of the peasant himself in increasing the fertility of the land in conditions of continuous land redistribution. By the 10-20s of the 20th century, otkhodnichestvo reached the peak of its development, to a large extent stimulated by the cooperative movement in the provinces, which had a gigantic pace and assumed outstanding proportions in Russia in the 20s. But then, quite soon, otkhodnichestvo completely disappeared due to the beginning of industrialization and collectivization. Both of these interconnected processes of the country’s socio-economic development did not imply any free initiative forms of labor behavior, and this is precisely the essence of otkhodnichestvo. What are its most important features?

The most important features that define both the traditional otkhodnichestvo of the 18th - early 20th centuries and the modern one at the turn of the 20th - 21st centuries and distinguish it from other forms of labor migration of the population are the following.

Firstly, this is the temporary, seasonal nature of a person’s departure (departure) from his place of permanent residence with a mandatory return home. The otkhodnik, almost always a man, went fishing after finishing field work, in the fall or winter, and returned to the beginning of spring work. The otkhodnik's family, his wife, children, parents, remained at home and managed a large peasant farm, where the otkhodnik still played the role of owner and manager of affairs. However, quite a few otkhodniks (usually from labor-abundant central provinces) also worked during the summer season, hiring themselves out as loaders, barge haulers, or day laborers. However, these were predominantly young, familyless and landless male farmers, who were not supported by either agricultural work or family, although they were controlled by the community, which paid taxes for them. We see exactly the same seasonal nature of the departure from family of almost always male otkhodniks today.

Secondly, this was the forced departure, since natural conditions did not allow on the spot to provide the peasant family with food in the required quantities and to produce an additional product for sale in order to have money. Therefore, otkhodnichestvo was most widespread in the non-chernozem provinces of the central zone and north of European Russia. In the black earth provinces, in the south and beyond the Urals, it practically did not occur, with the exception of the above-mentioned special case, but widespread by the middle of the 19th century on the Russian Plain, when the population density exceeded the “capacity of the land.” Even within the same province, the intensity of waste could vary greatly from county to county, depending on soil fertility. The compulsion of modern otkhodniki in the provinces is due to the absence or low quality of jobs - essentially the same local shortage of resources necessary for life.

The third distinctive feature of otkhodnichestvo was its hired and industrial nature. Obtaining additional income on the side was ensured through crafts - manufacturing and selling products of various crafts, from felting felt boots and sewing fur coats to rafting timber and making log houses, as well as hiring for various jobs in cities (watchmen and janitors, domestic servants) or in rich industrial and southern agricultural areas (barge haulers, loaders, day laborers, etc.). Today's otkhodniks are also often producers of products (the same log cabins) or services (carriage services, including taxi drivers and truck drivers in their own vehicles), directly offering them on the market. But now many more of them are hired workers, often performing unskilled types of work (security guards, watchmen, watchmen, janitors, cleaners, etc.).

Fourthly, and finally, the most important feature of otkhodnichestvo was its initiative and amateur character. Each person, having “corrected his passport” or “received a ticket,” could leave his place of residence for up to a year and offer services on the market in accordance with his professional skills, hiring for work or offering the products of his handicrafts. Otkhodniks often went to the fisheries in family teams of several people, usually brothers or fathers with adult children. These artels were narrowly professional, representing one separate “profession” or type of activity, such as “katals” who felted felt boots, saddlers who sewed fur coats or ofenis, Russian amateur “travelling salesmen” peddling icons, books and other “intellectual” products .

The combination of the listed characteristics of otkhodnichestvo makes it possible to distinguish this type of labor migration into a special form, significantly different from other methods of movement in the labor market. And it was precisely because of these specific features that otkhodnichestvo could not exist in Soviet times. Not only was mass self-employment of the population impossible, but also massive seasonal movements of people around the country. The artisanal nature of the crafts gave way to the industrial production of “consumer goods,” which destroyed the very soil for otkhodnichestvo. Forms of labor migration that were possible in the Soviet years, such as, for example, shift work and organizational recruitment (“recruitment” and “recruited”), distribution after college and free settlement after serving time in camps and zones (“chemistry”), as well as exotic forms such as “shabashka” and “flagellation” did not have the above-mentioned signs of otkhodnichestvo and could not be put in any logical connection with this form of labor migration.

On the contrary, during the years of systemic crisis, when the country’s economy was too quickly “rebuilt” to accommodate “new economic structures,” new forms of labor migration began to develop. There has been a renovation of otkhodnichestvo as one of the most effective, and now the most widespread, livelihood model. The condition for such a revival of otkhodnichestvo was a new form of “enslavement” of the population - now it is an “apartment fortress”, the absence of mass rental housing and affordable mortgages, preventing families from changing their place of residence. I believe that without this form of “fortress,” modern otkhodnichestvo would not have arisen. What is it? Let us present an outline of the phenomenon, based on the results of our field studies of otkhodnichestvo in 2009-2012.

Our main field research was carried out in 2011 and 2012 with the financial support of the Khamovniki charitable foundation. But we also conducted occasional studies of otkhodnichestvo in 2009-2010. Thus, over the past four years, a group of young researchers under my leadership has been systematically collecting materials related to modern otkhodnichestvo. Simultaneously with the collection of materials, the methodology for studying otkhodnichestvo was also developed. Due to the characteristics of the object, we could not usefully apply routine sociological methods based on formal questionnaire surveys and quantitative methods for describing the phenomenon. The emphasis was on qualitative methods, on conducting observations directly in small towns where otkhodniks live, and on interviews with them, their families and neighbors. Many additional materials, such as statistical and reporting data from local authorities, archival sources, were of secondary importance. The general information given below about the current Russian otkhodnichestvo and about otkhodniks is based precisely on interviews and direct observations in two dozen small towns in the European part of Russia and some Siberian regions.

The development of modern otkhodnichestvo, despite its short period of time - less than twenty years - has, in my opinion, already gone through two stages. The first characterized the actual emergence and growth of mass waste in small towns in the European part of the country, the second stage was the movement of sources of waste to the east of the country and “inland”, from small towns to villages.

The most important feature of the first stage was the rapid resumption (restoration) of otkhodnichestvo in small towns, mainly in the same areas as in imperial times. This process in the mid-1990s was initiated by the predominant action of two factors. The first is the complete absence of the labor market in small towns due to the “collapse” of all production in them, the stoppage and bankruptcy of large and small state-owned enterprises in the early 1990s. The sudden lack of work and, accordingly, means of livelihood for many families in such cities was aggravated by the underdevelopment or even complete absence of subsidiary farming, which, in turn, made it much easier for rural families to survive the collapse of collective and state farms in those days. In the early 1990s, I visited villages where I was told about cases of starvation deaths. In those years, up to half or more of all schoolchildren ate mainly at school, because there was nothing to eat at home. This fact was widespread in small towns and villages, and therefore was not even considered a social catastrophe. It was precisely this hopeless situation of urban families, left without work and without a farm, that forced people to hastily look for new sources of livelihood, among which waste fishing every year - as the labor market developed in regional and capital cities - became an increasingly widespread source.

But if this first factor was the driving force behind the departure, then the second - the inability of the family to move closer to the place of work due to the well-known features of our housing system (despite, or rather even thanks to the very conditional privatization of housing) - was precisely the factor that determined the specifics of labor migration in the form of otkhodnichestvo. Without “attachment” to an apartment, to a house, modern otkhodnichestvo would not have acquired its current proportions. Soviet people were sufficiently prepared for a change of residence: after all, according to experts, in the 1990s, the scale of forced relocations in the first half of the decade after the collapse of the Union reached 50 million people - every sixth family was “put on wheels.” But for most families, the costs of moving to a new permanent place of residence turned out to be higher than the costs associated with a long but temporary absence of one family member.

The second stage in the development of modern otkhodnichestvo has been taking shape since the early 2000s, is occurring before our eyes and is characterized by its shift from regional centers (small towns and villages) to the countryside. This, in my opinion, was caused by economic stabilization and growth, which led to the restoration of previous enterprises in small towns and the emergence of many new ones. In addition to the new jobs that brought former otkhodniks home, there were other interesting changes in the employment structure of the population associated, according to Kordonsky, with “the completion of the vertical of power to the district level” carried out in the first two terms of V.V. Putin’s presidency, especially starting since March 2004. As a result, in regional centers - our small towns and villages - the number of public sector employees has increased significantly, including employees of the regional and federal levels of government. Now the share of state employees in the employed population usually reaches 40, and in some places even 60-70% of the working population - and precisely in regional centers, which were a little earlier the main places of waste. These two reasons - the growth of local production and the development of the public sector - at the very least, but began to help reduce the scale of otkhodnichestvo in small towns. But the path had already been trodden, and “a holy place is never empty”: the jobs left in the capitals by otkhodniks from the cities were replaced by otkhodniks from the villages. If previously unemployed men from the village looked for work in the regional center, now an increasing number of them, following the paths indicated to them by their colleagues from the regional centers, go to the city (region) or to the Moscow region and earn a living there.

Standing somewhat apart is the process of shifting otkhodnichestvo to the east of the country, which coincides in time with the shift of retreat to rural areas in the west, but is not due to the same factors. In imperial times, otkhodnichestvo (with the exception of horse-drawn carriage over long distances) was completely alien to the rich villages and cities of Siberia. The population there did not need to find additional income, being small in number, eating from fertile lands and having sufficient funds from hunting, fishing, cattle breeding, logging, mining of precious metals and many other industries. Nowadays, facts of obvious otkhodnichestvo are being discovered everywhere in Siberia. As far as I can judge, based on so far episodic observations of this phenomenon, structurally, otkhodnichestvo in Siberia differs from European otkhodnichestvo in the following significant details. Firstly, the urban population does not participate in it on any large scale; Mostly residents of small towns and villages go to waste. Secondly, otkhodnichestvo here seems to be linked to the rotational form of labor migration. People are hired at construction sites and enterprises, mines and mines, responding to official advertisements. But unlike rotational recruitment, they do this on their own, and teams are also staffed on their own, often interacting with the employer at the level of the artel, and not the individual worker. It is the initiative and activity of a labor migrant that is for us an essential feature that distinguishes an otkhodnik from a shift worker (recruited through organizational recruitment). It is very difficult to identify this feature during remote analysis.

Naturally, modern otkhodniks do not always offer the products of their labor on the market themselves, as was the case before, when a significant part of otkhodniks were artisans who went to the market with their products. Now only a few can be considered such, for example, carpenters who make log houses, bathhouses and other wooden buildings and offer their products on the abundant market of the Moscow region and regional cities. And part of the previously artisanal production of household items, necessary in everyday life, but produced by otkhodniks, has now moved to a different, so-called ethno-format. The production of felted shoes, wicker chairs, clay pots and other handicrafts is now offered as part of the tourism business. In some places where tourists gather, the number of otkhodniks imitating local residents can be considerable.

The content of the otkhodnik's activity has changed compared to imperial times: the otkhodnik became more of a hired worker than an individual entrepreneur (handicraftsman). The main types of occupation of modern otkhodniks are very few. A survey of more than five thousand people allowed us to record no more than one and a half dozen types of activities, whereas a century ago in every large village it was possible to count up to fifty different types of related professions. Now this is mainly construction, transport (there are also those who carry out long-distance transportation on their own trucks, but many are hired as taxi drivers or drivers in organizations), services (various types of utilities associated with construction), trade (such as hawker stalls in city markets, and in supermarkets). The security business is especially popular: a large army of security guards in offices and enterprises in large cities consists almost exclusively of otkhodniks. Hiring at large enterprises for the production of a variety of types of work is carried out by organized groups, brigades made up of friends and relatives (artel principle). As a rule, such teams perform auxiliary, menial types of work.

A fact that deserves special attention is the high degree of conservatism of the types of latrine fisheries in traditional otkhodnichie territories. Modern otkhodniks “remembered” not only their grandfather’s trades, they also reproduced the main professions that were characteristic of these places a hundred years ago. Thus, the otkhodniks of Kologriv, Chukhloma and Soligalich in the Kostroma region chose the construction of wooden houses (making and transporting log houses) as the main type of latrine trade, and the residents of Kasimov, Temnikov, Ardatov, Alatyr are mostly hired as security guards and go into trade.

The directions of withdrawal today are slightly different than a century ago, but if we take into account the factor of changes in the administrative-territorial division of the country, we will have to admit that there is great conservatism in the directions of withdrawal. If earlier the Volga region was drawn mainly to St. Petersburg, now it is to Moscow. In both cases - to the capital. It’s the same with regional cities: when the regional center changes, the direction of departure from the regional cities changes accordingly. If earlier Mordovian otkhodniks went to Nizhny, Penza and Moscow, now they go to Saransk and Moscow.

The geography of otkhodnichestvo has expanded, but not radically. And in the 19th century they traveled from Kargopol and Veliky Ustyug to Kronstadt and Tiflis to be hired as servants and janitors. And now they are traveling from Temnikov to Yakutia to mine diamonds, from Toropets and Kashin to Krasnodar to harvest beets. Since the speed of movement over the century has increased by an order of magnitude, the movements of the otkhodniks themselves have become more frequent. Now, at distances from 100 to 600-700 km, they travel for a week or two, and not as before - for six months or a year. But in structural terms, the geography of otkhodnichestvo probably remained the same. As before, up to 50% of all otkhodniks do not go far, but look for extra work in the vicinity of 200-300 km from home. At least 75% of all otkhodniks leave for distances of up to 500-800 km (this corresponds to traveling by train or car for about half a day). About a quarter of otkhodniks already leave for longer distances, when travel time begins to make up a significant share of working time (more than 10%). People calculate in great detail and accurately the economic components of their difficult activities - and not only the time costs, but also the share of earnings brought into the household.

How much money does an otkhodnik bring home? Contrary to popular belief, the otkhodnik, on average, does not transport “large thousands” home. Earning money on the side greatly depends on qualifications and type of activity. Builders-carpenters earn up to half a million per season, based on a monthly salary of 50 and even 100 thousand rubles. But in terms of a month they will have 30-50 thousand. Those working in industry, transport and construction earn less - from 30 to 70 thousand, but work almost all year round. Less qualified otkhodniks earn up to 20-25 thousand, and security guards - up to 15 thousand (but we must keep in mind that they work two weeks a month). For a year it turns out 300-500 thousand rubles for a qualified otkhodnik and 150-200 thousand for an unskilled one. This earnings are on average higher than if a person worked in his own city, where the average earnings do not exceed 100-150 thousand rubles per year. In most small towns and villages, the salary of a public sector employee now ranges from 5 to 10-12 thousand rubles, that is, about 100 thousand a year, but finding a job for even 10 thousand locally is almost impossible - all the places are filled.

So it’s profitable to be an otkhodnik. True, a highly qualified otkhodnik, and then in comparison with his neighbors who are state employees or unemployed. Because if you subtract the expenses that the otkhodnik is forced to bear while working, then the result will not be such a large amount. According to our data, despite the usually extremely poor living conditions of a otkhodnik at his place of work, despite his desire to save his earnings as much as possible and bring more money home, with an average salary of 35-40 thousand rubles, he is forced to spend about 15 thousand rubles a month on his accommodation in the city. Usually housing costs about 5 thousand (in regional cities and capitals they spend almost the same on housing, but in the capital they rent housing for 5-10 people and often sleep in shifts). An otkhodnik spends approximately the same amount on poor food with “instant food.” Transport and other expenses (extremely rare entertainment) take another 5 thousand from him. So the otkhodnik does not bring home 50-70 thousand, as he says, but usually no more than 20-25 thousand monthly. Otkhodnik security guards, with a low salary of 15 thousand, have free overnight accommodation and live within a radius of up to 500 km from the capitals, so they manage to bring home up to 10 thousand a month.

What does the otkhodnik have at home? Here he has a family, a farm and neighbors. A very important fact: none of the otkhodniks are going to move to the city or the capital to live closer to work. They all want to live where they live now. And they want to work here. But they are not satisfied with what they have or could have, since the needs of these people are higher than the available supply. This feature - higher material demands - is what distinguishes otkhodniks from their neighbors, who do not want to go into otkhodnik. By the way, this same quality distinguished the otkhodniks from their neighbors a century ago.

Why do they need higher demands than their neighbors? The otkhodnik wants to spend additional income on very specific items of family expenses. He wants to ensure the well-being of his family at a decent level. Almost all otkhodniks have the same basic expenses. There are four of them. This is the renovation or construction of a house (including the construction of a new one for adult children). On average, from 50 to 150 thousand rubles are spent per year on repairs and construction. Secondly - a car (now often two), as well as a tractor, cultivator, truck, snowmobile and even an ATV. Typical spending on equipment is 50-100 thousand per year. Transport is necessary for the otkhodnik to work - many of them now prefer to travel as a team by car (train costs have become significantly higher than before). Transport is a means of additional income in the off-season (part-time work carrying people and lumber, firewood and manure; a tractor in a small town and village is like a horse in previous years - plowing a garden, shoveling snow, etc. - these are all types of very popular work). Of course, to a city dweller, a snowmobile and an ATV seem like entertainment (this is true for him), but in the provinces this transport helps people both in collecting wild plants (mushrooms and berries) and in obtaining game (used in hunting). In the third place, the money earned is put aside for savings for future or current expenses of the family, for the vocational education of children and their living in the city. Since most children study in the regional city, the cost of education is also 70-100 thousand (about 30-60 thousand is tuition fees and up to 40-50 thousand goes to pay for fairly cheap housing, the rest is added by working students themselves). Finally, this is entertainment - vacation spending - many otkhodniks annually take their wives and children to foreign resorts, spending an average of 80-100 thousand on such an activity.

It is on these four main items of necessary and prestigious expenses that otkhodniks spend all their earnings. The structure of expenses, therefore, in the families of otkhodniks may differ greatly from that in the families of state employees or pensioners. Since otkhodniks stand out from their neighbors on this basis, this contributes to the development of envy and hostile attitudes towards them. This was the case in the 1990s (although the shuttles mostly caused envy and discontent), but in the 2000s the share of otkhodniks among the population increased greatly, and now they have rather become trendsetters; envious neighbors look up to them and try to keep up. In general, otkhodniks have normal and good relations with their neighbors; the neighbors have long understood how hard the work of an otkhodnik is; envy is replaced by pity. And the neighbors do not see the prestigious consumption of the otkhodnik: stories about where they have been and on what beaches they sunbathed are not luxury cars and rich furniture; there is nothing to envy with one’s own eyes.

But the real social status of the otkhodnik is not the envy of his neighbors. An otkhodnik in local society often does not have many of the resources that a public sector employee is allowed to access, especially a public sector employee in the civil service. In a small town, a person who receives a salary that is an order of magnitude smaller than the salary of an otkhodnik has significantly greater opportunities for access to a variety of intangible resources, to power, to local shortages, to information, finally. The family of an otkhodnik does not yet feel discrimination in the field of general education, but there are already signs of this, manifested in the availability of health care services, especially when it comes to complex operations and rare medications that are distributed as a shortage. The differences in access to the “social welfare trough” are more pronounced: it is more difficult for an otkhodnik to receive various benefits, and it is practically very difficult to register a disability (a very useful benefit that many people dream of; this is why, in particular, we have so many “disabled people” in our country). Families of otkhodniks face greater difficulties than their neighbors, for example, in such a specific area of the household economy as supporting the family at the expense of adopted children: the chance of organizing a family orphanage is lower. In other words, in a social state these people, although in all respects indistinguishable from others, still find themselves further from the “feeding trough”.

The reason for this seems to me to be the “remoteness from the state” of people with this lifestyle. Neither local municipal authorities, much less state authorities, “see” these people either as labor resources or as objects of care worthy of public benefits. A significant portion of otkhodniks do not register their activities and provide services without going through the state. The state does not eat the fruits of their labor. Their movements across cities and regions cannot be traced. They are uncontrollable, not “registered”, not “fortified”. Meanwhile, if we proceed from our assumption that almost 40% of all Russian families participate in latrine trades, then the volume of production activity of such a mass of people “invisible” to the state (and therefore “shadow”) seems enormous. But does the state really need this “huge invisible man”? He, almost excluded from social state programs, outside state control of the economy, is also excluded from political activity. Although otkhodniks participate in the “electoral process” (although many argue that they do not go to elections), they are by and large uninteresting to the authorities as unimportant political subjects. Much more important for the authorities - and especially for the municipal ones - are those who want to “receive a salary” and have regular and stable pension transfers. The well-being and peace of mind of local officials depends on them, state employees and pensioners, and he pays primary attention to them. Otkhodnik is too aloof from local authorities. He can probably be useful to her only in that he is part of the permanent population on the municipal territory and a share of grants and subsidies received by the local administration for the development of the entrusted territory is allocated per capita. It is this “per capita share”, as an accounting demographic unit, that the otkhodnik is only useful for. True, they say that he brings in a lot of money and thereby seems to stimulate the economy of the region, increasing the purchasing power of the population. This is usually the only argument in favor of the otkhodnik. But is this really so important for the local administration? Moreover, the main waste of the money brought by the otkhodnik occurs not in the region, not in his city, but again in large cities - he buys building materials and cars not in his city, he also does not teach his children here, and his wife spends it on vacation the money is not here.

So we have the paradox of the “invisibility” of the huge, although existing next to us, phenomenon of modern otkhodnichestvo. But the existence of otkhodnichestvo as a fact of the social life of the country forces us to discuss not only economic, but also social and political consequences that could or are already arising from it. What might these consequences be? In fact, the situation of segregated interaction between local authorities and different groups of the local population, which is now observed everywhere, leads to a disruption of the system of relationships between the institution of municipal government and local society. Local authorities focus not on the active part of society, but on “rental” groups of the population, state employees and pensioners, who, on the one hand, are entirely dependent on the resources distributed by the state, but on the other, actively participate in the electoral process. Groups of the active population - first of all and predominantly the active amateur population, entrepreneurs and otkhodniks - fall out of the sight of local government bodies. Such a deep institutional deficit determines the distortion of the entire management system at the local level; it ceases to be effective. Violation of interaction between the authorities and the most active and independent part of local society closes the possibility of bringing local public administration to that higher level, which, in the general opinion, is characterized by such an important feature as inclusion in the system of civil society institutions. The participation of the “rental” population will never ensure the development of civil society. Moreover, rent recipients are interested exclusively in distributive, distribution relations, and not in partnership relations, which are absolutely necessary for building civil institutions. So, not noticing and diligently avoiding those who alone can act as an ally of the authorities in creating a new political reality with developed elements of civil society, the authorities are destroying the foundation of social stability. We see the first results of this destruction in various forms of alienation and neglect of power on the part of the active part of our society, which are increasingly clearly demonstrated.

If we talk about the possible social consequences of dividing local society into active and passive parts, then the following risks are seen here. Russian local (provincial) society is highly united and has significant potential for self-organization. A large proportion of active amateur people in it is in itself an important condition for stability and solidarity. However, if in such an environment a factor begins to operate that splits society and contributes to the emergence of confrontation between population groups, the prospects for social development are unfavorable. The worst thing is that the institution of power now acts as such a factor. Its destructive effect is aimed not only at social solidarity, it also suppresses the development of the institution of local self-government. Thus, a situation arises when otkhodnichestvo as a new social phenomenon, formed to solve the problems of immediate life support, in the conditions of completely routine actions of the social state, which by its nature is focused on supporting the passive part of society, can become a breeding ground for the growth of social tension and nurture the shoots new relationships that split the traditional stability of provincial society.

Acknowledgments

Our empirical research into contemporary otkhodnichestvo was funded from three sources. The main funds were allocated by the Khamovniki Charitable Foundation, partially in 2010-2011, and a special grant for the study of otkhodniks was received in 2011-2012 (grant No. 2011-001 “Otkhodniks in Small Towns”). In 2011, financial support was provided by the Russian Humanitarian Scientific Foundation for expeditions on this topic (grant No. 11-03-18022e). In 2012, research into the interaction of the active population (including otkhodniks) with municipal authorities was supported by a grant from the Scientific Foundation of the National Research University Higher School of Economics (grant No. 11-01-0063 “Will the economically active population become an ally of the municipal authorities? Analysis of violations in the system of relationships between institutions of local society and authorities ").

Significant work on collecting field material in 2009-2012 was carried out under my leadership by a group of young researchers - Ya. D. Zausaeva, N. N. Zhidkevich and A. A. Pozanenko. In addition to these main researchers, 14 more people, graduate students and students of the Faculty of State and Municipal Administration of the National Research University Higher School of Economics, occasionally took part in the work of collecting materials. It gives me great pleasure to express my gratitude to all participants in the study.

100 thousand rubles correspond to approximately 3 thousand US dollars. With the current average salary of a public sector employee in the province being $200-300 per month, the tenfold higher wage for an otkhodnik turns out to be a powerful incentive, despite any negative circumstances. In addition, people like to brag and somewhat inflate their earnings when they share their successes with friends.

We made an amusing observation during our trips: the estates of many otkhodniks have a characteristic difference from the estates of their neighbors in that they have many different buildings in the yard, and the house itself is covered with outbuildings, the walls and roofs of which are made of different materials. Naturally, the assumption arose that any repairs and new construction begin when money appears, and the otkhodnik’s money is irregular, and that is why the numerous extensions built at different times are so different in material and design.

What was the share of peasant otkhodniks in different regions of Russia? How did otkhodnichestvo affect the serf system? These and other issues related to peasant industrial otkhodnichestvo are considered in his article by S.V. Chernikov.

The article was published in the book "Images of Agrarian Russia in the 9th-18th centuries." (M.: Indrik, 2013.)

The problem of the formation of a capitalist structure in Russia has a fairly extensive historiography. At present, the most widespread point of view remains that similar economic relations developed in industrial production at the end of the 18th century. An important argument in favor of this position remains the fact of the active expansion of the civilian labor market. So, since the 60s. XVIII century and by the end of the century, the number of hired workers in factories and shipping increased from 220 to 420 thousand people 1 . A special place was occupied by light industry, serviced almost exclusively by civilian labor. The products produced were in high demand, which created opportunities for capital accumulation 2 .

However, in our opinion, the other side of this process is no less significant. After all, the main contingent of hired workers in various branches of production were peasant otkhodniks. The question remains open of how the spread of peasant subsistence livelihoods affected the dominant type of economic relations in the Russian countryside—serfdom. This is the problem that this work is devoted to.

First of all, we should dwell on the reasons for the active growth of peasant waste and fishing activity in general. The main one was the low level of agricultural production, which often did not meet the minimum needs of peasant farming 3 .

In historical literature, the generally accepted annual nutritional norm for an adult is considered to be 3 quarters (24 pounds) of grain, which is about 3200 kcal. per day. If we include in the given “norm” the needs of a peasant household for feeding livestock, then if there are 1-2 horses on farm 4, there will be from 12.5 to 18 pounds of grain left per peasant. In this case, the farmer’s daily diet will consist of 1700-2400 kcal, that is, 50-75% of the “norm” 5. But a long-term reduction in consumption standards (i.e., constant malnutrition) in conditions of heavy physical labor of the peasant is not possible. Consequently, if the cost of feeding livestock is calculated in excess of the indicated 24 poods, then for one person (in a two-horse farm) a net grain harvest of 35.5 poods (4.4 quarters) will be required.

Let us consider the possibilities of agricultural production in European Russia to meet the above needs. In Table. 1 presents data on net grain harvests per capita in the 1780-1790s. across 27 provinces 6.

Table 1. Level of agricultural production in European Russia in the 80-90s. XVIII century

As we see, even the lowest “norm” (3 quarters of grain per year per person) was not met by any province in the Central Non-Black Earth and Eastern regions. In the Northern region, net grain harvests per capita reached 3 quarters only in the Pskov province 7 . In the Black Earth Region, out of 6 provinces, there was a slight deficit (0.2-0.4 quarters) in two - Kursk and Tambov. In the Volga region, out of three provinces, a deficit was observed in one - Simbirsk (1.2 quarters). Only in the Baltic provinces (Revel and Riga) the grain surplus amounted to 2.5-3.0 quarters. Average data for the regions indicate grain surpluses in the Baltic states (2.8 quarters), the Central Black Sea region (0.6 quarters) and the Volga region (0.5 quarters).

If we consider the norm of consumption per capita (taking into account feeding of livestock) 4.4 quarters. grains per year, then a positive grain balance can be observed only in the Baltic states, as well as in Tula (surplus 0.8 quarters), Penza (0.4 quarters) and Oryol (0.2 quarters) provinces. The greatest shortage of bread was observed in the Central Chernozem Region (2.5 quarters), Northern (2.4 quarters), Eastern (2.7 quarters) regions, less significant - in the Central Black Earth Region (0.8 quarters) and the Volga region ( 0.9 quarters).

Based on data from the 1750s - early 1770s. In European Russia, the most numerous category of farmers (landowner peasants) was provided with grain on average below the norm by 3 quarters (24 poods). There were 21 poods per eater per year. Taking into account property groups, in the poorest group (35.9% of households) there was a shortage of 5.6 poods, in the middle group (48.9% of households) - 4.1 poods. Wealthy peasants (15.2% of households) had a surplus of 3.1 poods. The differentiation by forms of rent was as follows: in corvée holdings there was a surplus of 2.6 poods per eater, in quitrent holdings there was a shortage of 3.9 poods. In the regions, only the peasantry of the Black Earth Region and the entire wealthy elite of the serf village had a positive grain balance (if we consider 3 quarters per consumer as the “norm”).

Thus, it is obvious that the situation in the southern black earth and Volga provinces was saved only by periodic high harvests, and the regions of the center, north and east of European Russia as a whole (with average harvests - 2-3) were unable to provide themselves with grain even for peasant nutrition and livestock feed.

This level of agricultural development was typical for these territories and could be significantly changed only with the help of agrotechnical innovations. However, their implementation has been extremely slow 9 . We emphasize that the share of marketable grain (i.e., in fact, surplus consumption), according to calculations by V.K. Yatsunsky and I.D. Kovalchenko, at the beginning of the 19th century. amounted to only 9-14%, and in the middle of the century - 17% of the gross grain harvest. For the second half of the 18th - first half of the 19th centuries. Labor productivity in industry increased by approximately 8.6 times, and in agriculture - by only 14% 10 .

Consequently, the only means capable of ensuring the survival of the peasant in the infertile regions of European Russia (both at the end of the 18th century and in earlier and later periods) was to receive income from non-agricultural industries. However, legislative restrictions in the sphere of peasant industry and trade until the 2nd half of the 18th century prevented the development of this area of the economy.

The rise in this area was caused by changes in government policy from the early 60s. XVIII century The basis of the new course was the principles of freedom of enterprise in trade and industry, monopolies and privileges were gradually abolished, which was caused by the needs of the further development of the country and the fiscal interests of the treasury. 18th century In many farms of this region, there is a reduction in arable land, a massive transfer of estates to quitrents is taking place, a characteristic phenomenon for the 2nd half of the century is an increase in quitrents, and in-kind duties are converted into money 11.

Landowners, trying to increase the profitability of serf labor and obtain the highest possible quitrent payments, were also interested in income from peasant crafts. We emphasize that measures of strict landowner control and regulation of the activities of peasants here were combined with patronage and encouragement of their initiatives in the field of agricultural and industrial production, crafts and trade.

Among the main types of patronage activities of landowners in relation to peasant otkhodniks, the following can be distinguished 12. Thus, in particular, they used the transportation of peasant goods under the guise of landowners' goods, the issuance of preferential travel receipts and certificates that expanded the rights of peasants to wholesale and retail trade. Landowners opened fairs and markets on their own estates, registered peasant enterprises, large farm-outs and contracts in their own names, issued cash loans to peasants, and provided otkhodniks with residential and business premises in the cities. Influential landowners used personal connections to resolve litigation among their trading peasants. Attention was paid to the study of market conditions: lists of specialties were compiled that brought high profits in St. Petersburg and Moscow, a search was made for the most profitable work for their peasants, and metropolitan market prices and demand for handicrafts were determined.

There is also direct coercion of the peasantry to engage in fishing activities during periods free from field work. So, in the instructions of the book. MM. Shcherbatov contains the following demand: “Because the peasant, living at home, cannot make a big profit for himself, and for this he not only lets him go, but also forces them to go to work, and whenever the peasants demand passports, the clerk immediately gives them to them.” In the “order” of A.T. Bolotov, the basis of the landowner economy was the corvee system. However, “in case of lack of work,” the peasants should have been “released... to hire with a profit satisfactory to the master.” The peasant withdrawal was clearly linked to the need for peasants to pay the per capita tax, which was a cash and not a tax in kind (“This release to work not only of those who are overworked, but also those who are taxed is necessary in the autumn and winter to generate per capita money”). "Establishment" gr. P.A. Rumyantsev for his Nizhny Novgorod estate (1751-1777) contains a special section devoted to the organization of crafts and trade activities of peasants, and in the instructions of the book. MM. Shcherbatov (on the Yaroslavl estate, 1758) and S.K. Naryshkin (on the Krapiven estate, 1775) we find provisions on teaching peasants skills 13.

The second side of the relationship between the landowner and the peasant-otkhodnik, as already mentioned above, was the detailed regulation of the life and business activities of the serf 14. Peasants could leave the village only with the permission of the patrimonial authorities, which was confirmed by the issuance of “written leave” and printed passports. Typically, departure was allowed only in winter after completion of agricultural work, and in large trade and fishing villages - for one to two years. The landowners determined the terms, the number of otkhodniks, the departure of peasants was allowed only in the absence of arrears and the presence of guarantors (usually the closest relatives acted in this capacity - father, brother, father-in-law, son-in-law; less often - fellow villagers), who were responsible for the state and property duties of the otkhodniks. Punishments were established for the untimely return of otkhodniks to their patrimony. The hiring of undocumented and fugitive workers from other estates was not allowed (although there were numerous cases of violations). Sometimes the use of any outside hired labor was prohibited altogether. The landowner regulated monetary relations in the village, limited rental transactions with land within the community and on the outside. Bans were practiced on trading peasant property, grain and livestock without the permission of the clerk. This was caused by fear of a decrease in the solvency of the peasants, their ruin and increased social hostility in the community. Landowners were also afraid of competition from their own serfs, and therefore bans on trade in certain types of products were introduced for peasants. The Central Black Earth Region (compared to the Non-Black Earth Region) is characterized by more significant restrictions in the field of peasant waste, since corvee farming in the South of Russia brought significant profits.

All of the above measures complemented each other and varied depending on the region and the characteristics of the economic situation in a particular estate. In general, there is no reason to talk about the “contradictory nature” of the landowner’s relationship with peasant crafts, since both encouragement and regulation served a single goal - to maximize income from the use of serf labor.

The level of development of crafts and peasant farming in various regions of the country was inversely proportional to the degree of profitability of the agricultural sector. The dependence of the peasantry on income in the non-agricultural sphere was most clearly manifested in the Non-Black Earth Region. So, according to M.F. Prokhorov (1760-1770s), the share of peasant otkhodniks in the districts of the Moscow and Volga-Oka regions was the highest in European Russia (6-24.8% of the total male population). The leading place in the Non-Black Earth Region among otkhodniks was occupied by landowner peasants - 52.7%. But in proportion to the number of this or that group of peasants, the monasteries were in first place. The main reason for this was not the “inhibiting influence of the serf system on waste in the landowner village” (as M.F. Prokhorov believes), but the secularization of church estates, accompanied by the elimination of corvee and the transfer of economic peasants to quitrent 15. In the fertile Central Black Earth Region, these figures were significantly lower: in the northern part - 1.8-4.4%, in the central and southern counties - 0.9%. The leading place here (given the absence of corvée in the state village, as well as the social composition of the region’s population) was occupied by members of the same household and newly baptized people - 98% of otkhodniks. In the Middle Volga region, the share of otkhodniks was 2.3-3.8%, and in the Western and Northern regions - up to 6.2% 16.

For individual provinces there is the following data on the intensity of waste. In the Moscow province in 1799-1803. the number of otkhodniks (according to information on the number of passports issued to all categories of the population) was at the level of 45-65 thousand people, or 10-15% of the residents of the settlement, in the Yaroslavl province in 1778-1797. - 55-75 thousand people. or 15-23% of the male population. According to the “Description of the Kostroma Governorate” (1792), there were about 40 thousand otkhodniks in the province (more than 10% of the residents of the settlement). In the Kaluga province in the 60s. In the 18th century, according to a Senate questionnaire published in the Proceedings of the Free Economic Society, every third worker went to work. In certain districts of the Nizhny Novgorod province in the 80-90s. XVIII century otkhodniks accounted for at least 8% of the total male population. At the end of the century, in the Tambov province in the spring, up to 25 thousand people were sent to the ship fishery (Morshanskaya pier), in the Kursk province the number of otkhodniks reached 13 thousand. 17

The bulk of the otkhodnik peasants were employed in carting (usually in winter), in ship fishing (spring-autumn), in industrial enterprises (primarily textile ones), in construction in counties and in large cities. In the Central Chernobyl Region, employment is extended to agricultural work (haymaking, grain harvesting) and grazing. More often, otkhodniks went to large cities, mainly Moscow and St. Petersburg. Every year in the 1760-70s. up to 50 thousand people came to St. Petersburg and its environs, to Nizhny Novgorod - 25 thousand, Saratov - 7 thousand, Astrakhan - 6 thousand 18