One of the most tragic pages in the history of the Volga village was the famine of 1932-1933. For a long time, this topic was taboo for researchers. When the bans were lifted, the first publications concerning this topic appeared. However, sources unconventional for historians have not yet been used to reveal it. These are civil registration books of death, birth and marriage for the period from 1927 to 1940 for 582 rural Soviets stored in the archives of the Civil Registry Office of the Saratov and Penza regional executive committees and 31 archives of the Civil Registry Office of the district executive committees of these regions. In addition, in 46 villages of 28 rural districts of the Saratov and Penza regions, a survey of those who experienced all its hardships and hardships was conducted using a specially compiled questionnaire “Witness of the famine of 1932-1933 in a village in the Volga region.” It contains three groups of questions: the causes of famine, life in the village during the famine, and the consequences of famine. A total of 277 questionnaires were received and processed.

The regions of the Saratov and Penza regions occupy approximately a third of the Volga region. In the early 30s, their territory was divided between the Lower Volga and Middle Volga regions; on a significant part of the modern territory of the Saratov region there were cantons of the Autonomous Republic of Volga Germans (NP ASSR). Specializing in grain production and being one of the most fertile regions of the country, this part of the Volga region in 1932-1933. found herself in the grip of hunger. The mortality rate on the territory of all the rural Soviets studied in 1933, compared with the immediate previous and subsequent years, increased sharply. In 40 former districts of the Lower Volga and Middle Volga territories, on average in 1933 compared to 1927-1932 and 1934-1935. it increased 3.4 times. Such a jump could be caused by only one reason - hunger.

It is known that in starving areas, due to the lack of normal food, people were forced to eat surrogates and this led to an increase in mortality from diseases of the digestive system. Register books for 1933 show a sharp increase (2.5 times). In the column “cause of death” the following entries appeared: “from bloody diarrhea”, “from hemorrhoidal bleeding due to the use of surrogate”, “from poisoning with grout”, “from poisoning with surrogate bread”. Mortality has also increased significantly due to such reasons as “inflammation of the intestines,” “stomach pain,” “abdominal disease,” etc.

Another factor that caused an increase in mortality in 1933 in this region of the Volga region was infectious diseases: typhus, dysentery, malaria, etc. Entries in the register books allow us to talk about the occurrence of outbreaks of typhus and malaria here. In the village Kozhevino (Lower Volga region) in 1933, out of 228 deaths, 81 died from typhus and 125 from malaria. The following figures speak about the scale of the tragedy in the village: in 1931, 20 people died there from typhus and malaria, in 1932 - 23, and in 1933 - over 200. Acute infectious (typhoid, dysentery) and massive infectious diseases (malaria) always accompany hunger.

The register books also indicate other causes of death of the population in 1933, which were absent in the past, but now determined the increase in mortality and directly indicate hunger: many peasants died “from hunger,” “from hunger strike,” “from lack of bread,” “from exhaustion.” the body due to starvation”, “from malnutrition of bread”, “from starvation”, “from hunger edema”, “from complete exhaustion of the body due to insufficient nutrition”, etc. In the village. In Alekseevka, out of 161 deaths, 101 died from hunger.

Of the 61,861 death certificates available in the reviewed registers, only 3,043 reports mention hunger as a direct cause in 22 of the 40 surveyed districts. This, however, does not mean that in other areas in 1933 no one died of hunger; on the contrary, here too the sharp jump in mortality indicates the opposite. The discrepancy between the entry in death certificates and its real cause is explained by the fact that the work of civil registry offices in famine-stricken areas was influenced by the general political situation in the country. Through the mouth of Stalin, it was announced to the whole country and the whole world that in 1933 “collective farmers forgot about ruin and hunger” and rose “to the position of wealthy people.”

Under these conditions, the majority of registry office workers who registered deaths simply did not enter the forbidden word “hunger” in the appropriate column. The fact that it was illegal is evidenced by the order of the OGPU of Engels to the city registry office to prohibit it in 1932-1933. record the diagnosis “died of hunger.” This was justified by the fact that “counter-revolutionary elements” who allegedly clogged the statistical apparatus “tried to motivate every case of death with hunger, in order to thicken the colors necessary for certain anti-Soviet circles.” Civil registry office workers, when registering those who died of hunger, were forced to change the cause of death. According to the Sergievsky village council in 1933, 120 out of 130 deaths were registered as dying “for unknown reasons.” If we take into account that in 1932 only 24 people died there and the causes of their death were precisely determined in the register books, and the next year the mortality rate increased more than 5 times, then the conclusion suggests itself about the onset of severe famine, the victims of which were those who died from “ for unknown reasons."

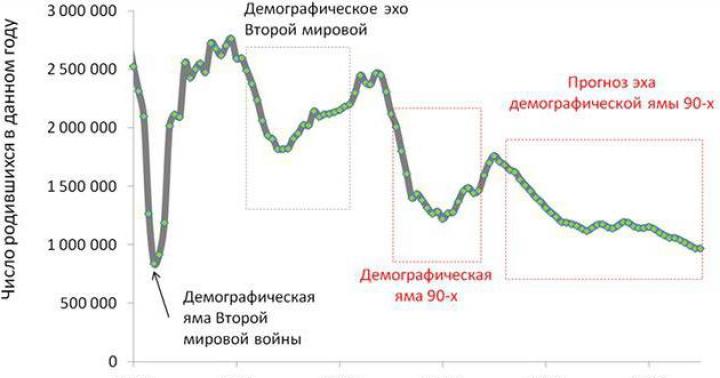

The fact of the onset of famine in 1932-1933. in the studied areas is also confirmed by such a demographic indicator, which always indicates famine, as a drop in the birth rate. In 1933-1934. The birth rate here has dropped significantly compared to recent previous years. If in 1927 148 births were registered on the territory of the Pervomaisky village council, in 1928 - 114, in 1929 -108, in 1930 - 77, in 1931 - 92, in 1932 - 75, then in 1933 there were only 19, and in 1934 - 7 births.

In Novoburassky, Engelssky, Rivne, Krasnoarmeysky, Marksovsky, Dergachevsky, Ozinsky, Dukhovnitsky, Petrovsky, Baltaysky, Bazarno-Karabulaksky, Lysogorsky, Ershovsky, Rtishchevsky, Arkadaksky, Turkovsky, Romanovsky, Fedorovsky, Atkarsky, Samoilovsky districts of the Saratov region. and in Kameshkirsky, Kondolsky, Nyakolsky, Gorodishchensky and Lopatinsky districts of the Penza region. in 1933-1934 the birth rate fell 3.3 times compared to its average level for 1929-1932. The reasons for this phenomenon were the high mortality rate of potential parents during famine; the outflow of the adult population, which has reduced the number of potential parents; a decrease in the adult population's ability to reproduce offspring due to physical weakening of the body as a result of starvation.

Influenced the birth rate in 1933-1934. The increased mortality rate in 1933 for this category of potential parents, such as young people, is confirmed by a significant decrease in the number of registered marriages in rural areas in those years. For example, the number of marriages registered in 1927-1929. in Petrovsky, Atkarsky, Rivne, Kalininsky, Marksovsky, Balashovsky, Ershovsky, Turkovsky, Arkadaksky districts of the Saratov region. decreased by an average of 2.5 times.

The epicenter of the famine, characterized by the highest mortality rate and the lowest birth rate, was apparently located in the Saratov region, on the Right Bank and in the left bank cantons of the Autonomous Republic of the Volga Germans. In 1933, the mortality rate of the rural population on the Right Bank compared with the average mortality rate in 1927-1932 and 1934-1935. increased by 4.5 times, on the Left Bank - by 2.6 times, in the territory of the studied areas of the NP ASSR - by 4.1 times. Birth rate in 1933-1934 compared to its average level in 1929-1932. fell on the Right Bank by 4 times, on the Left Bank by 3.8 times, in the areas of the NP ASSR by 7.2 times. As a result of the famine, the vitality of the Volga village was significantly undermined. This is evidenced by a sharp drop in the birth rate in many Saratov and Penza villages: judging by the entries in the register books, in many villages as many weddings were no longer held and as many children were not born as in the years preceding collectivization and famine.

Famine 1932-1933 left a deep mark in people's memory. “In the year thirty-three we ate all the quinoa. Hands and feet were swollen, dying on the move,” old-timers of Saratov and Penza villages recalled a ditty that reflected the people’s assessment of this tragedy. During the questionnaire survey, 99.9% confirmed the existence of a famine in 1932-1933, and also confirmed that it was weaker than the famine of 1921-1922, but stronger than the famine of 1946-1947. In many areas the scale of famine was very great. Villages such as Ivlevka, Atkarsky district, Starye Grivki, Turkovsky district, collective farm named after. Sverdlov of the Fedorov canton of the NP ASSR, almost completely died out. “During the war, not as many people died in these villages as died during the famine,” eyewitnesses recalled.

In many villages there were common graves (pits), in which, often without coffins, sometimes entire families buried those who died of starvation. 80 of the more than 300 respondents had close relatives who died during the famine. Eyewitnesses witnessed facts of cannibalism in such villages as Simonovka, Novaya Ivanovka of the Balandinsky district, Ivlevka - Atkarsky, Zaletovka - Petrovsky, Ogarevka, Novye Burasy - Novoburassky, Novo-Repnoye - Ershovsky, Kalmantai - Volsky districts, Shumeika - Engelssky and Semenovka - Fedorovsky cantons NP ASSR, Kozlovka - Lopatinsky district.

The American historian R. Conquest expressed the opinion that on the Volga famine broke out “in areas partially inhabited by Russians and Ukrainians, but the German settlements were most affected by it.” On this basis, he concludes that the NP ASSR “apparently was the main target of terror by famine.” Indeed, in 1933, the mortality rate of the rural population in the studied areas of this republic was very high, and the birth rate in this and subsequent years fell sharply. A team of writers led by B. Pilnyak, who probably visited there in 1933, reported about severe famine and facts of mass mortality of the population in a special letter to Stalin. In the famine-stricken cantons, cases of cannibalism were recorded. Memories of the famine of both Germans and representatives of other nationalities living on the territory of the republic at that time speak of the mass famine that occurred there in 1932-1933.

Comparative analysis of personal data obtained as a result of a survey of witnesses of the famine in the Mordovian village. Settlement of the Baltai district, Mordovian-Chuvash village. Eremkino, Khvalynsky district, Chuvash village. Kalmantai Volsky district, Tatar village. Osinovyi Gai and Lithuanian village. Chernaya Padina of the Ershovsky district, in the Ukrainian villages of Shumeika of the Engelssky and Semenovka of the Fedorovsky cantons and in 40 Russian villages, showed that the severity of hunger was very strong not only in the areas of the NP ASSR, but also in many Saratov and Penza villages located outside its borders .

“What was it: organized famine or drought?” - this question was asked in a letter to the editor of the journal “Questions of History” by A. A. Orlova. The onset of famine in the Volga region, including in the studied areas, was usually (in 1921 and 1946) associated with droughts and crop shortages. Drought is a natural phenomenon here. 75% of respondents denied the existence of a severe drought in 1932-1933; the rest indicated that there was drought in 1931 and 1932, but not as severe as in 1921 and 1946, when it led to shortages and famine. Special literature mainly confirms the assessment of climatic conditions of 1931-1933 given by witnesses of the famine. In publications on this topic, when listing a long series of dry years in the Volga region in 1932 and 1933. fall out. Scientists noted a drought that was average according to the accepted classification and weaker than the droughts of 1921, 1924, 1927, and 1946 only in 1931. The spring and summer of 1932 were typical for the Volga region: hot, in places with dry winds, not ideal for crops, especially in the Volga region, but in general the weather is assessed by experts as favorable for the harvest of all field crops. The weather, of course, influenced the decrease in grain yields, but there was no mass crop shortage in 1932.

Interviewed old-timers of Saratov and Penza villages testified that, despite all the costs of collectivization (dekulakization, which deprived the village of thousands of experienced grain growers; a sharp reduction in the number of livestock as a result of their mass slaughter, etc.), in 1932 it was still possible to grow a crop quite sufficient to feed the population and prevent mass starvation. “There was bread in the village in 1932,” they recalled. In 1932, the gross harvest of grain crops in all sectors of agriculture in the Lower Volga region amounted to 32,388.9 thousand centners, only 11.6% less than in 1929; in the Middle Volga Territory -45,331.4 thousand centners, even 7.5% more than in 1929. Overall, the 1932 harvest was average for recent years. It was quite enough to not only prevent mass starvation, but also to hand over a certain part to the state.

Collectivization, which significantly worsened the financial situation of the peasantry and led to a general decline in agriculture, did not, however, cause mass famine in this Volga region. In 1932-1933 it occurred not as a result of drought and crop shortages, as was previously the case in the Volga region, and not because of complete collectivization, but as a result of forced Stalinist grain procurements. This was the first artificially organized famine in the history of the Volga village.

Only 5 out of more than 300 interviewed eyewitnesses of the events of 1932-1933. did not recognize the connection between grain procurements and the onset of famine. The rest either named them as the main cause of the tragedy, or did not deny their negative impact on the food situation of the village. “There was a famine because the grain was handed over,” “every grain, down to the grain, was taken out to the state,” “they tormented us with grain procurements,” “there was a surplus appropriation, all the grain was taken away,” the peasants said.

By the beginning of 1932, the village was weakened by collectivization, grain procurements in 1931, and not entirely favorable weather conditions of the past year, which caused crop shortages in some areas. Many peasants were already starving then. Basic agricultural work was very difficult. An intensive exodus of peasants to cities and other parts of the country began, resembling a flight. And in this situation, the country's leadership, which was aware of the situation in the Volga region, approved in 1932 clearly inflated plans for grain procurements for the Lower and Middle Volga. At the same time, the difficulties of the organizational and economic development of the newly created collective farms were not taken into account, as eloquently evidenced by the mass protests of the chairmen of collective farms and village councils, district party and Soviet bodies, sent to the regional leadership.

Despite the energetic efforts of the party and economic leadership, which practiced in September - November the removal from work and expulsion from the party of district leaders who “thwarted the plan”; putting on “black boards” collective farms, settlements, and districts that do not fulfill the plan; he declared an economic boycott and other measures; grain procurement plans were not fulfilled. The situation changed in December 1932, when, at the direction of Stalin, a commission of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks on grain procurement issues, headed by the Secretary of the Party Central Committee P. P. Postyshev, arrived in the region. It seems that the assessment of the work of this commission and its chairman, which is available in the literature, requires clarification, if not revision.

The commission and Postyshev personally (as well as V. M. Molotov, who visited Ukraine, and L. M. Kaganovich - in Ukraine and the North Caucasus) are responsible for the artificially organized famine in the Volga region in question. It was under pressure from the commission of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks (its members, in addition to Postyshev, included Zykov, Goldin and Shklyar) that the local leadership, fearing reprisals for disrupting grain procurements, in order to fulfill the plan, confiscated the bread earned by collective farmers for workdays and available to individual farmers. This ultimately led to mass famine in the village.

The following facts speak about the methods of work of Postyshev and his commission, which demanded that the grain procurement plan be fulfilled at any cost. Only in December 1932, for failure to fulfill the grain procurement plan, by the decisions of the bureau of the Lower Volga Regional Party Committee, at whose meetings were members of the Central Committee commission and Postyshev himself, 9 secretaries of district committees and 3 chairmen of district executive committees were removed from their jobs; many were subsequently expelled from the party and put on trial. During meetings with local party and economic activists on grain procurement issues (participants of such meetings in the city of Balashov, I. A. Nikulin and P. M. Tyrin spoke about this) right in the hall where these meetings were held, on the instructions of Postyshev, for failure to comply During the grain procurement plan, secretaries of district party committees were removed from their jobs and OGPU workers arrested collective farm chairmen. In words and in the press, Postyshev opposed the confiscation of grain from collective farms that fulfilled the plan, against violations of the law during grain procurements, but in reality he took a tough position that pushed the local leadership to take illegal measures against those who did not fulfill the plan.

At the end of December 1932 - beginning of January 1933, a real war began against collective farms and individual farms that did not fulfill the plan. The decision of the bureau of the Lower Volga regional party committee dated January 3 stated: “The regional committee and the regional executive committee demand from the district executive committees and district committees of districts that have disrupted the plan, unconditional fulfillment of the grain procurement plan by January 5, without stopping at additional procurement in collective farms that have fulfilled the plan, allowing partial refunds from collective farmers' advances." District Soviet authorities were allowed to begin checking the “stolen grain” by collective farmers and individual farmers.

Numerous eyewitness accounts indicate how these directives were implemented in Saratov and Penza villages. The peasants were confiscated from the bread they had earned during their workdays, including what was left over from previous years; they did not give out bread for workdays; they exported seed grain. Violence was often used against peasants during grain procurements. In the village Botsmanovo, Turkovsky district, grain procurement commissioner from Balashov Shevchenko, in order to “knock out” bread, locked up almost the entire village in a barn (testifies M.E. Dubrovin, who lives in the working-class village of Turki, Saratov region). “They came, they forcibly took the bread and took it away,” “they gave it, and then took it away,” “they went from house to house, taking away bread and potatoes; those who resisted were put in a barn for the night,” “[bread] was pulled out of the oven,” recalled old-timers of Saratov and Penza villages.

To fulfill the plan, grain was exported not only on horses, but also on cows. The chairman of the Studeno-Ivanovsky collective farm of the Turkovsky district, M. A. Goryunov (lives in Turki), was ordered by the grain procurement commissioner to allocate collective farm horses to assist the neighboring collective farm in exporting grain. The horses made two flights and covered over 100 km; The chairman did not agree to send them on a third voyage: “We’ll kill the horses!” He was forced to comply, and soon 24 horses had died. The chairman was put on trial because he refused to find the collective farm grooms guilty of the death of horses (they say they were poorly fed), as the commissioner advised him. Violence was also used in carrying out the plan to pour seeds into public barns. Local activists often walked around the yards and looked for bread; everything that was found was taken away.

The organizers of the procurement explained to the peasants that the grain would go to the working class and the Red Army, but there were persistent rumors in the villages that in fact the grain was being taken away in order to export it abroad. It was then that sad ditties and sayings appeared in the village: “Rye and wheat were sent abroad, and the gypsy quinoa was sent to collective farmers for food,” “Shingles, stillage, corn were sent to the Soviet Union, and rye and wheat were sent abroad,” “Our burner.” the grain-bearing woman gave away the bread, she was hungry.” Many peasants associated grain procurements and the ensuing famine with the names of Stalin and Kalinin. “In 1932, Stalin made a fill, and that’s why famine occurred,” they said in the villages. In the ditties, the singing of which was punishable by imprisonment, the words sounded: “When Lenin was alive, we were fed. When Stalin arrived, they starved us.”

In 1933, in the Volga region there were rumors that a “Stalinist pumping of gold” was being carried out: a hunger strike was carried out in order to take gold, silver and other valuables from the population through Torgsin stores for next to nothing, in exchange for food. The peasants explained the organization of the famine through grain procurements by Kalinin’s desire to punish them for their unwillingness to work conscientiously on collective farms and to accustom the peasants to collective farms. In Saratov and Penza villages in 1933, there was a rumor that, like the famous trainer Durov, who taught animals to obey by hunger, Kalinin decided to use hunger to accustom the peasants to collective farms: if they endure hunger, it means they will get used to collective farms, will work better and appreciate collective farm life.

During the grain procurements of 1932, which doomed the village to famine, there was no open mass resistance from the peasants. The majority of respondents explained this by fear of the authorities and the belief that the state will provide assistance to the village. And yet there were exceptions. In the village Red Key of the Rtishchevsky district, testifies S. N. Fedotov (lives in the city of Rtishchevo, Saratov region), having learned about the decision to export seed grain, almost the entire village gathered at the barn where it was stored; The peasants tore down the castle and divided the grain among themselves. In the village In the darkness of the same area (told by I. T. Artyushin, who lives in the city of Rtishchevo), there was a mass uprising of peasants, which was suppressed by the police.

The main forms of peasant protest against forced grain procurements were hidden actions: attacks on the “red convoys” that were transporting grain from villages, the theft of grain from these convoys, and the dismantling of bridges. Some peasants openly expressed their dissatisfaction with the organizers of grain procurements; repressive measures were applied to them (testimony of M.A. Fedotov from the working-class village of Novye Burasy, S.M. Berdenkov from the village of Trubechino, Turkovsky district, A.G. Semikin from the working-class village of Turki, Saratov region).

Thus, data from archival documents and interviews with eyewitnesses of the events indicate that the forced grain procurements of 1932 left the Volga region village without bread and became the main cause of the tragedy that took place there in 1933. The mass famine caused by grain procurements carried out in violation of the law and morality, which claimed tens of thousands of peasant lives and undermined the health of the survivors, is one of the gravest crimes of Stalinism, its organized inhumane action.

Read also on this topic:

Notes

1. See, for example, I. E. ZELENIN. About some “blank spots” of the final stage of complete collectivization. - History of the USSR, 1989, No. 2, p. 16-17; Problems of oral history in the USSR (abstracts of a scientific conference on November 28-29, 1989 in Kirov). Kirov. 1990, p. 18-22.

2. Archive of the Civil Registry Office of the Petrovsky District Executive Committee of the Saratov Region, death certificate books for the Kozhevinsky Village Council for 1931-1933.

3. Archive of the Civil Registry Office of the Novoburassky District Executive Committee of the Saratov Region, death certificate book for the Novo-Alekseevsky Village Council for 1933.

4. Lenin and Stalin about labor. M. 1941, p. 547, 548, 554, 555.

5. Central State Archives of National Economy (TSGANH) of the USSR, f. 8040, op. 8, no. 5, pp. 479, 486.

6. Archive of the Civil Registry Office of the Arkadak District Executive Committee of the Saratov Region, death certificate books for the Sergievsky Village Council for 1932-1933.

7. Archive of the Civil Registry Office of the Rtishchevsky District Executive Committee of the Saratov Region, civil registration books of births for the Pervomaisky Village Council for the years 1927-1934.

8. CONQUEST R. Harvest of sorrow. Soviet collectivization and terror by famine. London. 1988, p. 409, 410.

9. TsGANKH USSR, f. 8040, op. 8, no. 5, pp. 479-481, 483, 485, 486, 488.

10. Central party archive of the Institute of Marxism-Leninism under the Central Committee of the CPSU (CPA IML), f. 112, op. 34, no. 19, l. 20.

11. Questions of History, 1988, No. 12, p. 176-177.

12. Dry winds, their origin and the fight against them. M. 1957, p. 33; Droughts in the USSR, their origin, recurrence and impact on the harvest. L. 1958, p. 38,45,50,166-169; KABANOV P. G. Droughts in the Saratov region. Saratov. 1958, p. 2; Climate of the southeast of the European part of the USSR. Saratov. 1961, p. 125; KABANOV P. G., KASGROV V. G. Droughts in the Volga region. In the book: Scientific works of the Research Institute of Agriculture of the South-East. Vol. 31. [Saratov]. 1972, p. 137; Agriculture of the USSR. Yearbook. 1935. M. 1936, p. 270-271.

13. Agriculture of the USSR. Yearbook. 1935, p. 270-271.

14. CPA IML, f. 17, op. 21, no. 2550, pp. 29 vol., 305; d. 3757, l. 161; d. 3767, l. 184; No. 3768, pp. 70, 92; d. 3781, l. 150; d. 3782, l. eleven; Volzhskaya commune, 12-14. XI. 1932; Povolzhskaya Pravda, 15.29. X. 1932; Saratov worker, 2.1. 1933; Struggle, 30.XI. 1932.

15. See History of the USSR, 1989, No. 2, p. 16-17.

16. CPA IML, f. 17, op. 21, no. 3769, l. 9; No. 3768, pp. 139.153.

17. Ibid., no. 3768, pp. 118 vol., 129,130 vol., 148,153.

18. Ibid., no. 3769, l. 9.

19. Ibid., no. 3768, pp. 139.153.

By the beginning of the 30s, it was clear to the leadership of the USSR that it would not be possible to avoid a major war with the imperialist states. Stalin wrote about this in the article “On the tasks of business executives” like this: We are 50-100 years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this distance in ten years. Either we do this or we will be crushed.”

Having set the task of industrializing the country in 10 years, the leadership of the USSR was forced to accelerate the collectivization of the peasantry.

If initially, according to the collectivization plan, only 2% of peasant farms should have been collectivized by 1933, then according to the accelerated collectivization plan, collectivization in the main grain-producing regions of the USSR should have been completed in a year or two, that is, by 1931-1932.

By collectivizing peasants, Stalin sought to enlarge farms. It was relatively easy to seize produce from large farms. Agricultural products were the main export, providing currency for accelerated industrialization. And most importantly, only large, mechanized farms in the climatic conditions of our country could produce marketable grain.

The main problem of Russian peasants was weather and climatic conditions, a short warm season, and, consequently, the high burden of agricultural labor.

Chayanov, through a thorough statistical analysis of labor effort, income and expenses of peasant farms, proved that excessive labor can become a significant limiter on the growth of labor duration and productivity.

The law of A.V. Chayanov, if expressed in simple language, says that the burden of labor prevents the peasant from increasing labor productivity, and when prices for his products rise, he prefers to curtail production.

In accordance with Chayanov's law, under the NEP the average peasant began to eat better than in tsarist times, but practically stopped producing marketable grain. During the NEP, peasants began to consume 30 kg of meat per year, although before the revolution they consumed 16 kg per year.

This indicated that a significant part of the grain was redirected from supplies to the city to improve their own nutrition. By 1930, small-scale production had reached its maximum.

According to various sources, from 79 to 84 million tons of grain were harvested (in 1914, together with the Polish provinces, 77 million tons).

The NEP allowed a slight increase in agricultural production, but the production of commercial grain decreased by half. Previously, it was provided mainly by large landowner farms that were liquidated during the revolution.

The shortage of marketable grain gave rise to the idea of consolidating agricultural production through collectivization, which, in the geopolitical conditions of that time, became a necessary necessity, and was taken up with Bolshevik inflexibility.

For example, by October 1, 1931, collectivization in the Ukrainian SSR covered 72% of arable land and 68% of peasant farms. More than 300 thousand “kulaks” were expelled outside the Ukrainian SSR.

As a result of the restructuring of the economic activities of peasants associated with collectivization, a catastrophic decline in the level of agricultural technology occurred.

Several objective factors of that time worked to reduce agricultural technology. Perhaps the main thing is the loss of incentive to work hard, as the peasant’s work has always been during the “suffering”.

In the fall of 1931, more than 2 million hectares of winter crops were not sown, and losses from the 1931 harvest were estimated at up to 200 million poods; threshing in a number of areas took place until March 1932.

In a number of areas, seed material was submitted to the grain procurement plan. Most collective farms did not pay the collective farmers for workdays, or these payments were meager.

Labor activity fell even more: “they’ll take it away anyway,” and food prices in the cooperative network became 3-7 times higher than in neighboring republics. This led to a mass exodus of the working population “to buy bread.” In a number of collective farms, from 80 to 100% of able-bodied men left.

Forced industrialization led to a much larger outflow of people to cities and industrial areas than expected. The population of cities grew by 2.5 - 3 million per year, and the overwhelming majority of this increase was due to the most able-bodied men of the village.

In addition, the number of seasonal workers who did not live in cities permanently, but went there for a while in search of work, reached 4-5 million. The shortage of labor has noticeably worsened the quality of agricultural work.

In Ukraine, one of the important factors was the sharp reduction in the number of oxen, used as the main tax, during the process of collectivization. Peasants slaughtered livestock for meat in anticipation of their socialization.

Due to the growth of the urban population and the increased shortage of grain, the procurement of food resources for industrial centers began to be carried out at the expense of feed grain. In 1932, half as much grain was available for livestock feed as in 1930.

As a result, in the winter of 1931/32 there was the most dramatic reduction in the number of working and productive livestock since the beginning of collectivization.

6.6 million horses died - a quarter of the remaining draft animals; the rest of the livestock was extremely exhausted. The total number of horses decreased in the USSR from 32.1 million in 1928 to 17.3 million in 1933.

By the spring sowing of 1932, agriculture in the zones of “complete collectivization” came virtually without draft animals, and there was nothing to feed the socialized livestock.

Spring sowing was carried out in a number of areas manually, or plowed with cows.

So, by the beginning of the spring sowing season of 1932, the village approached a serious lack of draft power and a sharply deteriorated quality of labor resources. At the same time, the dream of “ploughing the land with tractors” was still a dream. The total power of tractors reached the figure planned for 1933 only seven years later; combine harvesters were just beginning to be used

A decrease in the incentive to work, a drop in the number of working and productive livestock, and spontaneous migration of the rural population predetermined a sharp decline in the quality of basic agricultural work.

.

As a result, the fields sown with grain in 1932 in Ukraine, the North Caucasus and other areas were overgrown with weeds. But the peasants, herded into newly created collective farms, and having already had experience “they will take it away anyway,” were in no hurry to show miracles of labor enthusiasm.

Even parts of the Red Army were sent to weeding work. But this did not help, and with a fairly tolerable biological harvest in 1931/32, sufficient to prevent mass starvation, grain losses during harvesting grew to unprecedented proportions.

If in 1931, according to the NK RKI, about 20% of the gross grain harvest was lost during harvesting, then in 1932 the losses were even greater. In Ukraine, up to 40% of the harvest remained standing; in the Lower and Middle Volga, losses reached 35.6% of the total gross grain harvest.

By the spring of 1932, severe food shortages began to appear in the main grain-producing areas

In the spring and early summer of 1932, in a number of areas, starving collective farmers and individual farmers mowed down unripe winter crops, dug up planted potatoes, etc.

Part of the seed aid provided to the Ukrainian SSR by the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks in March-June was used as food.

As of May 15, 1932, according to Pravda, 42% of the total sown area was sown.

By the beginning of the harvesting campaign in July 1932, more than 2.2 million hectares of spring crops were not sown in Ukraine, 2 million hectares of winter crops were not sown, and 0.8 million hectares were frozen.

The American historian Tauger, who studied the causes of the 1933 famine, believes that the crop failure was caused by an unusual combination of a set of reasons, among which drought played a minimal role, but the main role was played by plant diseases, an unusually wide spread of pests and grain shortages associated with the drought of 1931, rains in time of sowing and harvesting grain.

Whether it was natural reasons or the low level of agricultural technology due to the transition period of the formation of the collective farm system, the country was threatened with a sharp drop in the gross grain harvest.

Trying to rectify the situation, by decree of May 6, 1932, the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks lowered the grain procurement plan for the year. In order to stimulate the growth of grain production, the grain procurement plan was reduced from 22.4 million tons to 18.1 million, which is only a little more than a quarter of the predicted harvest.

But the grain yield forecasts that existed at that time, based on their biological productivity, significantly overestimated the actual indicators.

Thus, the grain procurement plan in 1932 was drawn up based on preliminary data about a higher harvest (in reality it turned out to be two to three times lower). And the party and administrative leadership of the country, after lowering the grain procurement plan, demanded strict adherence to the plan.

Harvesting in a number of areas was carried out ineffectively and belatedly, the ears stopped growing, crumbled, stacking was not carried out, loaf warmers were used without grain catchers, which further increased considerable grain losses.

The intensity of harvesting and threshing of the 1932 harvest was extremely low - “they will take it away anyway.”

In the fall of 1932, it became clear that in the main grain-producing regions the grain procurement plan was catastrophically not being fulfilled, which threatened the urban population with starvation and thwarted plans for accelerated industrialization.

So in Ukraine, at the beginning of October, only 35.3% of the plan was fulfilled.

The emergency measures taken to speed up the procurement helped little. By the end of October, only 39% of the annual plan had been fulfilled.

Expecting, as last year, non-payment of workdays, collective farm members began to steal grain en masse. In many collective farms, advances in kind were issued that significantly exceeded the established norms and inflated standards for public catering were indicated. Thus, the collective farm management circumvented the norm for the distribution of income only after the plans were fulfilled.

On November 5, in order to strengthen the struggle for grain, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Bolsheviks) proposes to the People's Commissariat of Justice, regional and district committees, along with the deployment of broad mass work, to ensure a decisive increase in assistance to grain procurements from the justice authorities.

It was necessary to oblige the judicial authorities to consider cases of grain procurements out of turn, as a rule, in mobile sessions on the spot with the use of severe repressions, while ensuring a differentiated approach to individual social groups, applying especially harsh measures to speculators and grain resellers.

In pursuance of the decision, a decree was issued, which stated the need to establish special supervision by prosecutors over the work of administrative bodies regarding the use of fines in relation to farms that fall far behind the grain delivery plan.

On November 18, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine adopted a new tough resolution, which plans to send 800 communist workers to villages where “kulak sabotage and disorganization of party work have become most acute.” https://ru.wikisource.org/wiki/Resolution_of_the_Politburo_of_the_Central_KP_KP (b) U_18_November_1932_"On_measures_to_strengthen_grain procurements"

The resolution outlines possible repressive measures against collective farms and individual farmers who do not fulfill grain procurement plans. Among them: 1. Prohibition of the creation of natural funds on collective farms that do not fulfill the procurement plan

2. A ban on the issuance of advances in kind on all collective farms that are unsatisfactorily fulfilling the grain procurement plan, with the immediate return of illegally issued grain in advance.

3. Confiscation of bread stolen from collective farms, from various kinds of grabbers and loafers who do not have workdays, but have reserves of grain.

4. To bring to court, as plunderers of state and public property, storekeepers, accountants, accountants, supply managers and weighers who hide grain from accounting and compile false accounting data in order to facilitate theft and embezzlement.

5. The import and sale of all manufactured goods, without exception, must be stopped in districts and individual villages, especially those that perform grain procurements unsatisfactorily.

After the release of this decree, excesses began in the localities with its implementation, and on November 29, the Politburo of the Central Committee (b) U issued a decree indicating the inadmissibility of excesses. (Annex 1)

Despite the adopted resolutions, both the delivery plan and

threshing of bread was significantly delayed. According to data as of December 1, 1932, in Ukraine, on an area of 725 thousand hectares, grains are not threshed.

Therefore, although the total volume of grain exports from the village through all channels (procurement, purchases at market prices, collective farm market) decreased in 1932–1933 by approximately 20% compared to previous years, due to low harvests, and with such exports Cases of virtually complete confiscation of collected grain from peasants were practiced. Famine began in areas of mass collectivization.

The question of the number of victims of the famine of 1932-1933 became the arena of a manipulative struggle, during which anti-Soviet activists in Russia and the entire post-Soviet space sought to increase the number of “victims of Stalinism” as much as possible. Ukrainian nationalists played a special role in these manipulations.

The theme of the mass famine of 1932-1933 in the Ukrainian SSR actually became the basis of the ideological policy of the leadership of post-Soviet Ukraine. Monuments to victims of the famine, museums and exhibitions dedicated to the tragedy of the 1930s were opened throughout Ukraine.

Exhibition displays sometimes became scandalous due to obvious manipulations with historical material (Appendix 3)

In 2006, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine declared the Holodomor a genocide of the Ukrainian people carried out with the aim of “suppressing the national liberation aspirations of Ukrainians and preventing the construction of an independent Ukrainian state.”

In the Russian Federation, anti-Soviet forces widely used the famine of 1932-33 as a weighty argument for the justice of transferring the country to capitalism. During Medvedev's presidency, the State Duma adopted a resolution condemning the actions of the Soviet authorities who organized the famine of 1932-33.

The resolution states:

“As a result of the famine caused by forced collectivization, many regions of the RSFSR, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, and Belarus suffered. The peoples of the USSR paid a huge price for industrialization... About 7 million people died in the USSR from hunger and diseases associated with malnutrition in 1932-1933.”

Almost the same number of deaths from the famine of 1932-33 was given by Goebbels propaganda during the Second World War

The famous Russian historian-archivist, V. Tsaplin, who headed the Russian State Archive of Economics, calls the figure 3.8 million people

In the school textbook on Russian history, in use since 2011, edited by Sakharov, the total number of famine victims is determined to be 3 million people. It also states that 1.5 million people died of hunger in Ukraine

The venerable ethnographer Professor Urlanis, in his calculations of losses from famine in the USSR in the early 1930s, gives a figure of 2.7 million

According to V. Kozhinov’s calculations, collectivization and famine led to the fact that in 1929–1933 the mortality rate in the country exceeded the mortality rate in the previous five years of NEP (1924–1928) by one and a half times. It must be said that a similar change in mortality rates in Russia took place starting in 1994 compared to the second half of the 80s.

According to Doctor of Historical Sciences Elena Osokina, the number of registered deaths exceeded the number of registered births, in particular, in the European part of the USSR as a whole - by 1975 thousand, and in the Ukrainian SSR - by 1459 thousand.

If we are based on the results of the All-Union Census of 1937 and recognize the natural mortality rate in Ukraine in 1933 as the average natural mortality rate for the years 1927-30, when there was no famine (524 thousand per year), then with a birth rate in 1933 of 621 years, in Ukraine there was natural population growth equal to 97 thousand. This is five times less than the average increase in the previous three years

It follows that 388 thousand people died from famine.

Materials “On the state of population registration of the Ukrainian SSR” for 1933 give 470,685 births and 1,850,256 deaths. That is, the number of residents decreased due to famine by almost 1,380 thousand people.

Zemskov gives approximately the same figure for Ukraine in his famous work “On the Question of the Scale of Repression in the USSR.”

The Institute of National Memory of Ukraine, naming the increasing number of Holodomor victims every year, began collecting a martyrology, “Books of Memory,” of all those who died of hunger. Requests were sent to all settlements of Ukraine about the number of deaths during the Holodomor and their national composition.

It was possible to collect the names of 882,510 citizens who died in those years. But, to the disappointment of the initiators, among those people whom the current Ukrainian government is trying to present as victims of the famine of the 30s, not the largest part actually died from hunger or malnutrition. A significant part of the deaths were from domestic causes: accidents, poisonings, criminal murders.

This is described in detail in the article by Vladimir Kornilov “Holodomor. Falsification on a national scale." In it, he analyzed data from the “Books of Memory” published by the Institute of National Memory of Ukraine.

The authors of the regional “Books of Memory”, out of bureaucratic zeal, entered into the registers all the dead and deceased from January 1, 1932 to December 31, 1933, regardless of the cause of death, sometimes duplicating some names, but were unable to collect more than 882,510 victims, which is quite comparable to the annual (!) mortality rate in modern Ukraine.

While, increasing every year, the official number of “Holodomor victims” reaches 15 million.

The situation is even worse with evidence of the “genocide of the Ukrainian people.” If we analyze the data for those cities of Central and Southern Ukraine, where local archivists decided to meticulously approach the matter and not hide the nationality column, which is “inconvenient” for the east of Ukraine.

For example, the compilers of the “Book of Memory” classified 1,467 people as “victims of the Holodomor” in the city of Berdyansk. Nationalities are indicated on the cards of 1,184 of them. Of these, 71% were ethnic Russians, 13% were Ukrainians, 16% were representatives of other ethnic groups.

As for villages and towns, you can find different numbers there. For example, data for the Novovasilievsky Council of the same Zaporozhye region: of the 41 “Holodomor victims” whose nationalities were indicated, 39 were Russian, 1 was Ukrainian (2-day-old Anna Chernova died with a diagnosis of “erysipelas,” which can hardly be attributed to hunger ) and 1 – Bulgarian (cause of death – “burnt”). And here is the data for the village of Vyacheslavka in the same region: of the 49 deaths with the specified nationality, 46 were Bulgarians, 1 each was Russian, Ukrainian and Moldovan. In Friedrichfeld, of the 28 “victims of the Holodomor,” one hundred percent are Germans.

Well, the lion’s share of the “Holodomor victims,” of course, came from the most populated industrial eastern regions. There were especially many of them among the miners. Absolutely all deaths from injuries received in production in Donbass or in mines are also attributed by the compilers of the “Book of Memory” to the results of hunger.

The idea of compiling “Books of Memory,” which obliged regional officials to search for documents related to the “Holodomor,” led to an effect that the initiators of the campaign did not expect.

Examining the documents that local executive officials included in the regional “Books of Memory of Holodomor Victims,” you do not find a single document confirming the thesis that then, in the 30s, the authorities took actions the purpose of which was to deliberately cause famine, and even more so completely exterminate the Ukrainian or any other ethnic group on the territory of Ukraine.

The authorities of that time - often on direct orders from Moscow - made sometimes belated, sometimes clumsy, but sincere and persistent efforts to overcome the tragedy and save people's lives. And this in no way fits into the concepts of modern falsifiers of history.

Annex 1

Resolution of the Politburo of the Central Committee (b) U dated November 29 “On the progress of implementation of Politburo resolutions of October 30 and November 18”,

1. The resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (b) U on funds in local collective farms is being simplified and distorted. The Central Committee once again warns that the application of this decision is a matter that requires great flexibility and knowledge of the actual situation on the collective farms.

Simply and mechanically transporting all funds to grain procurement is completely wrong and unacceptable. This is especially wrong with regard to the seed fund. The seizure of collective farm funds and their inspection should not be carried out indiscriminately, not everywhere. It is necessary to skillfully select collective farms in such a way that abuses and hidden grain are really discovered there.

A more limited number of inspections, but inspections that yield serious results, exposing saboteurs, kulaks, their accomplices, and decisive reprisal against them will put much more pressure on other collective farms, where the inspection has not yet been carried out, than a hasty, unprepared inspection of a large number of collective farms with insignificant results .

It is necessary to apply various forms and methods of this verification, individualizing each collective farm. In a number of cases, it is more profitable to use a hidden verification of funds without informing the collective farm about the verification. Where it is known that the check will not give serious results and is not beneficial to us, it is better to refuse it in advance.

The removal of at least part of the seed material should be allowed only in particularly exceptional cases, with the permission of the regional party committees and with the simultaneous adoption of measures that actually ensure the replenishment of this fund from other intra-collective farm sources.

For the unauthorized removal of at least part of the seed fund, the regional committees in relation to the PKK, and the PKK in relation to their authorized representatives, must apply strict penalties and immediately correct the mistakes made.

2. In the application of repression both to individual farmers, and especially against collective farms and collective farmers, in many regions they are already straying into mechanical and indiscriminate use, counting on the fact that the use of naked repression itself should provide bread. This is incorrect and certainly harmful practice.

Not a single repression, without the simultaneous deployment of political and organizational work, can give the result we need. While well-calculated repressions applied to skillfully selected collective farms, repressions carried through to the end, accompanied by appropriate party-mass work, give the desired result not only in those collective farms where they are applied, but also in neighboring collective farms that do not fulfill the plan.

Many grassroots workers believe that the use of repression frees them from the need to carry out mass work or makes it easier for them to do this work. Just the opposite. It is the use of repression as a last resort that makes our party work more difficult.

If we, taking advantage of the repression applied to the collective farm as a whole, to the directors or to the accountants and other officials of the collective farm, do not achieve the consolidation of our forces on the collective farm, do not achieve the unity of the activists in this matter, do not achieve real approval of this repression from the mass of collective farmers, then we will not get the necessary results regarding the implementation of the grain procurement plan.

In cases where we are dealing with an exceptionally unscrupulous, stubborn collective farm that has fallen entirely under kulak influence, it is necessary first of all to ensure support for this repression from the surrounding collective farms, to achieve condemnation and to organize pressure on such a collective farm from the public opinion of the surrounding collective farms.

All of the above does not mean at all that enough repression has already been applied and that at present in the regions they have organized really serious and decisive pressure on the kulak elements and the organizers of the sabotage of grain procurements.

On the contrary, the repressive measures provided for by the resolutions of the Central Committee in relation to kulak elements both on collective farms and among individual peasants have yet to be used very little and have not given the necessary results due to indecision and hesitation where repression is undoubtedly necessary.

3. The fight against kulak influence on collective farms is, first of all, a fight against theft, against the concealment of grain on collective farms. This is a fight against those who deceive the state, who directly or indirectly work against grain procurements, who organize sabotage of grain procurements.

Meanwhile, completely insufficient attention is paid to this in the regions. Against thieves, grabbers and grain plunderers, against those who deceive the proletarian state and collective farmers, at the same time as using repression, we must raise the hatred of the collective farm masses, we must ensure that the entire mass of collective farmers brand these people as kulak agents and class enemies.

Appendix 2.

Discussion of falsifications of the Holodomor topic on social networks.

1. The falsifications of the “Holodomor” continue to this day and take the form of a spectacle that is no longer even criminal, but something like a procession of feeble-minded, backward clowns. So recently, the Security Service of Ukraine was caught falsifying the “Ukrainian Holocaust” exhibition held in Sevastopol - the photographs were passed off by scammers from the Ukrainian special services as photographs of the “Holodomor”.

Without blinking an eye, the head of the Security Service of Ukraine, Valentin Nalyvaichenko, admitted that “part” of the photographs used in Sevastopol at the “Holodomor” exhibition were not authentic, because supposedly in Soviet times all (!) photographs from 1932-33 from Ukraine were destroyed, and now “they can be found with great difficulty and only in private archives.” This suggests that even in the archives of the special services there is no photo evidence

2. Cases of well-confirmed hunger are characterized by nutritional dystrophy. Most patients do not die, but become emaciated and turn into living skeletons.

The famine of 1921-22 showed mass degeneration, the famine of 1946-47 - mass degeneration, the Leningrad siege famine - also mass degeneration, prisoners of Nazi concentration camps - total degeneration.

The swelling of the starving people of 1932-33 is recorded everywhere, while dystrophy is very, very rare. There is evidence that swelling indicates poisoning by grain stored in improper conditions.

The grain was hidden in earthen pits; the grain was not cleaned of fungi, which is why it spoiled, becoming poisonous and life-threatening. So, often, people died from grain poisoning by grain pests such as smut and rust.

The costs of reforms aimed at accelerating industrial development turned out to be much greater than could have been expected at first, and were expressed not only in economic decline (per capita GDP in 1932, according to Angus Madison’s calculations, was lower than in 1930), but also in increased mortality from malnutrition. True, any estimates of the number of deaths as a result of this famine must be handled with great caution, since there are no direct sources for counting them, which led to the appearance of the most fantastic figures in the media.

We conducted a thorough analysis of various sources, including materials from the 1937 census, and obtained an estimate of excess mortality in 1932–1933 in the USSR in the amount of 4.2–4.3 million people, of which 1.9 million occurred in Ukraine, approximately 1 million - to the Kazakh ASSR, the rest was taken over by Russia, primarily the North Caucasus and the Volga region, as well as the Central and Central Black Earth regions, the Urals and Siberia.

Speaking about the reasons for the increased mortality in 1932–1933, we must first of all talk about what actually did not happen.

First. There was no increase in the amount of grain alienated by the state from collective farms and individual farmers. The grain procurement plan for 1932 and the volume of grain actually collected by the state were radically less than in the previous and subsequent years of the decade. The Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks lowered the grain procurement plan by a decree of May 6, 1932, which allowed collective farms and peasants to sell grain at free market prices.

In order to stimulate the growth of grain production, this decree reduced the grain procurement plan from 22.4 million tons (1931 quota) to 18.1 million, this is only a little more than a quarter of the predicted harvest. Therefore, it is impossible to say that the last things were raked out of the collective farmers. As partial compensation, the state increased the plan for state farms from 1.7 million tons to 2.5 million, and the total grain procurement plan amounted to 20.6 million tons. Since the preliminary plan drawn up by the People's Commissariat of Trade in December 1931 established a grain procurement plan of 29.5 million tons, the decree of May 6 actually reduced it by 30%. Subsequent decisions also reduced plans for procurement of other agricultural products.

In fact, the total volume of grain alienation from the village through all channels (procurement, purchases at market prices, collective farm market) decreased in 1932–1933 by approximately 20% compared to previous years. At the same time, since the beginning of the Five-Year Plan, more than 10 million former rural residents poured into industrial construction sites and cities, and the number of citizens receiving food on cards increased from 26 million in 1930 to 40 million in 1932. Bread standards were steadily declining, and bread rationing was often not fully issued. In the fall of 1932, the norms for Kyiv workers were cut from 2 to 1.5 pounds, and bread rations for employees - from 1 to 0.5 pounds (200 g). This is not much more than the norms of besieged Leningrad.

The fact that famine did not arise as a result of the redistribution of grain resources from villages to cities is also evidenced by the fact that it was not only rural people who were starving

Proving the cruelty and bloodiness of the Soviet regime, publicists used the “three ears of corn” law as an argument. According to a number of authors, this normative act was directly aimed at destroying the peasantry. However, in the works of researchers there is a different view of the situation.

Features of punishment

During the years the Criminal Code of the RSFSR was in force. It established different punishments for different crimes. The responsibility for the thefts, meanwhile, was quite small, one might even say symbolic. For example, for the first time, the theft of property without the use of technical means and without collusion with other persons was subject to forced labor or prison for up to 3 months. If the act was committed repeatedly or the object of the attack was material assets that were necessary for the victim, punishment was applied in the form of imprisonment for a period of up to six months. Repeated theft or theft carried out using technical means, as well as by prior conspiracy, was punishable by imprisonment for up to a year. The same punishment threatened an individual who committed theft without the specified conditions at piers, train stations, hotels, ships and in carriages. For theft from a public or state warehouse, other storage facility using technical means or in collusion with other persons, or repeatedly, forced labor for up to a year or imprisonment of up to 2 years was imposed. A similar punishment was intended for subjects who committed an act without the specified conditions when they had special access to objects or guarded them, as well as during a flood, fire or other natural disaster. For especially large-scale theft from public/state warehouses and storage facilities, as well as in the presence of special access to them, using technical means or in conspiracy with other criminals, up to 5 years in prison were imposed. As you can see, the punishments were quite lenient even in the presence of serious circumstances. Of course, such sanctions did not stop the attackers. The problem was further aggravated by the fact that as a result of collectivization, a new type of property appeared - public property. In essence, she was left without any legal protection.

Decree 7-8

The problem of theft has become acute in the country. J.V. Stalin, in a letter to Kaganovich, substantiated the need to approve a new regulatory act. In particular, he wrote that recently cargo thefts on railway transport have become too frequent. The damage was estimated at tens of millions of rubles. Cases of theft of collective farm and cooperative property have become more frequent. The thefts, as stated in the letter, were organized mainly by kulaks and other elements who sought to undermine the state system. According to the Criminal Code, these subjects were considered as ordinary thieves and received 2-3 years of “formal” prison. In practice, after 6-8 months. they were successfully amnestied. JV Stalin pointed out the need to tighten responsibility. He said that further connivance could lead to the most serious consequences. As a result, a resolution was adopted by the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR on August 7, 1932. Punishments for theft were significantly tightened. According to the normative act, theft of collective farm and cooperative property was punishable by up to 10 years in prison in the presence of mitigating circumstances. If the latter were absent, the death penalty was imposed. Such theft was punishable by execution and confiscation. The need to issue a normative act was determined by instability in the state. Many people, greedy for money, tried in every way to take advantage of the situation and extract as much benefit as possible.

Arbitrage practice

It is worth noting that the law “on three ears of corn” (as it began to be called among the people) began to be applied quite fanatically by the authorities. From the moment of its approval to January 1, 1933, the following were sentenced:

- At the highest level - 3.5%.

- By 10 years - 60.3%.

- 36.2% received a less severe punishment.

It must be said, however, that not all capital sentences were carried out in the USSR. 1932 was, to a certain extent, a trial period for the use of the new regulatory act. General authorities handed down 2,686 capital sentences. A large number of decisions were made by linear transport courts (812) and military tribunals (208). Nevertheless, the Supreme Court of the RSFSR revised almost half of the sentences. The Presidium of the Central Election Commission issued even more acquittal decisions. According to the records of Krylenko, People's Commissar of Justice, the total number of executed people did not exceed 1000.

Case review

A completely logical question arises: why did the Supreme Court begin to review the decisions of lower authorities? This happened because the latter, applying the law of “three ears of corn,” sometimes reached the point of absurdity. For example, serious punishment was imposed on three peasants who were characterized by the prosecution as kulaks, and by the certificates they themselves presented as middle peasants. They were convicted of taking a boat that belonged to a collective farm and going fishing. A serious sentence was also handed down to an entire family. People were convicted for fishing in the river that flowed next to the collective farm. Another absurd decision was made against the young man. He "played around with the girls in the barn, thereby disturbing a piglet that belonged to the collective farm." Since collective property was inviolable and sacred, the judge sentenced the young man to 10 years in prison “for disturbing.” As Vyshinsky, the famous prosecutor of that time, points out in his brochure, all these cases were regarded by judges as an encroachment on public material values, although in fact they were not such. At the same time, the author adds that such decisions are constantly overturned, and the judges themselves are removed from their positions. Nevertheless, as Vyshinsky noted, this whole reality is characterized by an insufficient level of understanding, a limited horizon of people capable of making such verdicts.

Examples of solutions

The accountant of one of the collective farms was sentenced to 10 years in prison for his careless attitude towards agricultural equipment, which was expressed in partially leaving it in the open air. However, the court did not establish whether the instruments were rendered partially or completely unusable. A oxman on one of the collective farms released bulls into the street during harvesting. One animal slipped and broke its leg. By order of the board, the ox was slaughtered. The People's Court sentenced the hauler to 10 years in prison. One of the ministers also fell under the law of “three ears of corn.” Having climbed the bell tower to remove the snow from it, he found corn there in 2 bags. The minister immediately reported this to the village council. People were sent to check and found a third bag of corn. The minister was sentenced to 10 years. A barn manager was sentenced to ten years for allegedly weighing people down. The audit revealed 375 kg of excess grain in one of the storage facilities. When considering the case, the people's court did not take into account the manager's statement about inspecting the remaining barns. The accused argued that due to the incorrect description of the statements, there must be a shortage of grain in the same quantity in the other store. After the verdict was pronounced, the manager’s statement was confirmed. One of the collective farmers was sentenced to 2 years in prison for taking a handful of grain into his palm and eating it, because he was hungry and exhausted, not having the strength to work. All these facts can serve as evidence of the cruelty of the then existing regime. However, illegal and essentially meaningless sentences were canceled almost immediately after they were adopted.

Government instructions

The sentences “for ears of corn” were a manifestation of arbitrariness and lawlessness. The state demanded that justice workers not allow the use of a normative act when this would lead to its discredit. In particular, the law “on three ears of corn” could not be applied in cases of theft on an extremely small scale or in the case of an extremely difficult financial situation of the perpetrator. Local judicial personnel were extremely unqualified. Combined with excessive zeal, this led to massive “excesses.” However, there was an active fight against them at the state level. In particular, authorized persons were required to apply Art. 162 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR, which provided for more lenient punishments. Higher authorities pointed out to lower authorities the need to correctly qualify acts. In addition, it was said about the unlawful non-application of the provision on mitigation of sanctions in difficult life situations.

Famine in the USSR 1932-1933

The situation in the country was extremely difficult. The plight was noted in the RSFSR, BSSR, the North Caucasus, the Volga region, the Southern Urals, Western Siberia, and Northern Kazakhstan. In the Ukrainian SSR, official sources indicate the name “Holodomor”. In Ukraine, in 2006, the Verkhovna Rada recognized it as an act of genocide of the people. The leadership of the former republic accused the Soviet government of deliberately exterminating the population. Sources indicate that this “man-made famine” led to huge multimillion-dollar casualties. Later, after the collapse of the Union, this situation was widely covered in the media and various official documents. The Holodomor in Ukraine was regarded by many leaders as one of the manifestations of an aggressive policy. However, as mentioned above, the disastrous situation also occurred in other republics, including the RSFSR.

Grain procurement

According to the results of research conducted by Doctor of Historical Sciences Kondrashin, the famine in the USSR of 1932-1933 was not the result of widespread collectivization. In some regions, for example, in the Volga region, the situation was due to forced grain procurements. This opinion is confirmed by a number of eyewitnesses of those events. The famine arose from the fact that the peasants had to hand over all the collected grain. suffered greatly from collectivization and dispossession. In the Volga region, the commission on grain procurement, under the leadership of the Secretary of the Party Central Committee Postyshev, issued a resolution on the confiscation of stocks from individual grain growers, as well as grain earned by collective farmers. Under pain of criminal punishment, chairmen and heads of administrations were forced to transfer almost the entire harvest to the state. All this deprived the region of food supplies, which provoked mass famine. The same measures were taken by Kaganovich and Molotov. Their decisions concerned the territories of the North Caucasus and Ukraine. As a result, mass death of the population began in the country. At the same time, it must be said that the grain procurement plan for 1932 and the volume of grain actually collected were significantly lower than in previous and subsequent years. The total amount of alienated grain from villages through all channels (markets, purchases, procurement) decreased by 20%. The volume of exports decreased from 5.2 million tons in 1931 to 1.73 in 1932. The following year it decreased even more - to 1.68 million tons. For the main grain-producing regions (Northern Caucasus and Ukraine), quotas for the quantity of procurement have been repeatedly reduced. For example, the Ukrainian SSR accounted for a quarter of the grain delivered, while in 1930 the volume was 35%. According to Zhuravlev, the famine was provoked by a sharp drop in harvests as a result of collectivization.

Results of application of the normative act

A note from the deputy chairman of the OGPU Prokofiev and the head of the economic department of the OGPU Mironov addressed to Stalin indicates that of the theft cases solved in two weeks, special attention was paid to major crimes that occurred in Rostov-on-Don. The theft spread throughout the local bakery system. Thefts occurred at mills, at the plant itself, in two bakeries, and in 33 stores where products were sold to the public. As a result of the inspections, the theft of more than 6 thousand pounds of bread, 1,000 of sugar, 500 of bran, etc. was established. Such chaos occurred due to the lack of clear reporting and control, as well as due to the criminal nepotism of employees. The workers' supervision, which was attached to the trading network, did not justify its purpose. In all cases, inspectors acted as accomplices to crimes, putting their signatures on obviously fictitious acts on the under-delivery of bread, write-off of shrinkage, etc. As a result of the investigation, 54 people were arrested, five of whom were members of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). In the Taganrog branch of Soyuztrans, an organization of 62 people was liquidated. Among them were port employees, loaders, drivers, most of whom were former kulaks, merchants, and criminal elements. As part of the organization, they stole cargo transported from the port. The volumes of stolen goods directly indicate that the participants in the crimes were clearly not peasants.

Conclusion

As a result of the application of the regulatory act, theft on railway transport and theft of state farm property, material assets from artels and cooperatives began to decrease. In January 1936, mass rehabilitation of convicted people began. A resolution was adopted on January 16, according to which the relevant cases were examined. As a result, some of the convicts, whose actions did not contain corpus delicti, were released from prison.

The black myth of the “Holodomor” is very versatile. Its supporters argue that collectivization in the USSR became the main cause of famine in the country; that the Soviet leadership deliberately organized the export of grain abroad, which led to an aggravation of the food situation in the country; that Stalin deliberately organized famine in the USSR and Ukraine (the myth of the “Holodomor in Ukraine”), etc.

The creators of this myth took well into account the fact that most people perceive information on an emotional level. If we talk about numerous victims - “millions and tens of millions”, the public consciousness falls under the magic of numbers and at the same time does not try to understand the phenomenon, to understand it. Everything fits into the formula: “Stalin, Beria and the Gulag.” In addition, when more than one generation has passed, society already lives more in illusions, myths, which the creative, free intelligentsia helpfully creates for them from year to year. And the intelligentsia in Russia, traditionally brought up on Western myths, hates any Russian state - Rus', the Russian Empire, the Red Empire and the current Russian Federation. The majority of the population of Russia (and the CIS countries) receives information about the USSR (and the Fatherland) not from small-circulation scientific literature, but with the help of “educational” programs of various Posners, Svanidzes, milky, artistic “historical” films, which give an extremely perverted, falsified picture, and even from an exclusively emotional point of view.

In the ruins of the USSR, the situation is further aggravated by the fact that the picture is heavily smeared with nationalist tones. Moscow, the Russian people, appear in the role of “oppressors”, “occupiers”, “bloody dictatorship”, which suppressed the best representatives of small nations, interfered with the development of culture and economy, and carried out outright genocide. Thus, one of the favorite myths of the Ukrainian nationalist “elite” and intelligentsia is the myth of a deliberate famine, which was caused with the aim of exterminating millions of Ukrainians. Naturally, the West strongly supports such sentiments; they fully fit into the plans for an information war against Russian civilization and the implementation of plans for a final solution to the “Russian question.” The West is interested in inciting nationalist passions, bestial enmity and hatred of Russia and the Russian people. By pitting the fragments of the Russian world against each other, the masters of the West save significant resources, and their potential enemy, in this case two branches of the Rus Superethnos - the Great Russians and the Little Russians, themselves destroy each other. Everything is in line with the ancient strategy of “divide and conquer.”

In particular, James Mace, author of the work “Communism and the Dilemmas of National Liberation: National Communism in Soviet Ukraine in 1919-1933,” concluded that the leadership of the USSR, strengthening its power, “destroyed the Ukrainian peasantry, the Ukrainian intelligentsia, the Ukrainian language, Ukrainian history in the understanding of the people, destroyed Ukraine as such.” Obviously, such conclusions are very popular among Nazi elements in Ukraine. However, the real facts of history completely refute such lies. Since the inclusion of Left Bank Ukraine into the Russian state under the Truce of Andrusov in 1667, Ukraine has only increased in territorial terms - including the inclusion of Crimea in the Ukrainian SSR under Khrushchev, and the population has been growing. “The destruction of Ukraine as such” led to an unprecedented cultural, scientific, economic and demographic prosperity of Ukraine. And we have seen the results of the activities of the governments of “independent” Ukraine in recent years: a reduction in the population by several million people, the split of the country along the West-East line, the emergence of preconditions for a civil war; degradation of spiritual culture and national economy; a sharp increase in political, financial and economic dependence on the West; rampant Nazi elements, etc.