We often see heated debates between active forum members from Mongolia and Kazakhstan on social networks. One of these discussions is about Mongolian writing, which we present on our website. Material unchanged:

Modern Mongolian has retained its ancient origins. The language has undergone changes over the years, but it still retains its roots. The current Mongols prove this every time with precision. translation I documents, letters from the 12th, 13th... centuries.

This translation from old Mongolian how the guys from Mongolia did it and how they did it translation historian Daniyarov Kalibek.

Kazakh historian D. Kalibek tried to translate the verse into medieval Mongolian. According to the Kazakhs and that historian, the transcription of Old Mongolian is in Latin and everything is almost clear to them. In fact, Kazakhs cannot understand because the Mongolian language is completely foreign to them.

Here is a poem in ancient Mongolian and modern Mongolian:

Erte udur – ece jeeinjisun okin-o- Onketen;\mng: Ert өdroөөs shinzhsen ohin Ongeten;

ulus ulu temecet-\mng:uls ulu temceed

Qasar qoa okid-i—-\mng:hatsar goa okhidig

Qaqan boluqsan – a taho—\mng:Khaan bolson ta ho

Qasaq terken – tur unoiju—\mng: Hasag tergendee unazh

Qara buura kolkeji——\mng:har buuraa hollozh-

Qataralsu otcu——-\mng:Khatirlaj odsu-\

Qatun saulumu ba—-\mng:Khatan suulgamu ba-

Ulus irken ulu te temecet ba—\mng:uls irgen vlV de temetsed ba—

Onke sait Okid-iyen ockeju—\mng:ongo site okidoo Osgozh—

Olijke tai terken-tur unouliu—\mng:Olzhigotoy tergend unuulyuu-

Ole buura kolkeju—\mng:өl buuraa khөllөzh—

Euskeju otcu—\mng:vvsgezh odsu—

Undur saurin-tur—\mng:өndөr suurin dur-

Orecle etet sauqui ba—\mng: өrgөl eded suuguy ba—\

Erfenece Kunqirat irket.—\mng:ertnees khongiraad irged—

Our daughters have been chosen for a long time

Our beautiful girls

To you who became khans (given)

We ride on tall, fast carts

We harness black camels (males) to them

And let's run fast

They become mistresses

They confront with the subjects of other uluses

We give away the best daughters

We put them on fast carts

We harness camels to them

And (to you) we take

They sit on a high place

For a long time, Khongirat subjects

Any Mongolian, having read this poem, will immediately understand that he is praising the beautiful, beautiful-faced Khongiraat girls, who have been marrying the khan for a long time, becoming the khansha\mistress\. Hongiraat is a Mongolian tribe. They now live in Mongolia.

And here the most interesting thing is “translated” by the same historian D. Kalibek in quotation marks))):

1.Qacar - Gasyr - Epoch\ this is not quite an EPOCH, here is the word Khatsar-cheeks, face, especially since here comes the Mongolian phrase Qasar qoa-khatsar goo-beautiful-faced,\

2.Qatun - Katyn - Wife\hatan is a mistress, khansha in Mongolian. It's a sin to make a mistake with a Khatan.\

3. Okid-i – Okidy – Teaches\ incorrect translation Teaches; and on MNG Okid-i-okhidiyg-girls\

4. Qaqan – Kagan – Ruler; \Khan, khan na mng. There's simply no room for error here. In many languages, khan, hag, kagan are king, ruler, head\

5. Qasaq terken tyr – Іазає тјрін стр – Kazakh relatives of the wife are standing—this is clearly not a coincidence))) in Mongolian it is written Khasag tergen dur - means in a BIG CART.

6. Erfenece kunqirat irken – Erte»nen konrat erkin – For a long time, konrat have been free.——there is no word freedom here. It’s just been written for a long time khongiraada and that’s it.

The main thing is to pay attention to his translation, why he could not write word for word in his Kazakh as we wrote in Mongolian in 30 minutes. It’s obvious that he just kind of fantasized about it and called the translation ohm. Thus, the man wanted to seem to understand the language of Genghis Khan, in fact he perfectly proved that he had nothing in common with the language of the great ancestors of the Mongols.

The Mongols of the 13th century spoke Mongolian, which we, the Mongols of the 21st century, understand. But the Turks, including Kalibek Daniyarov, can only understand individual words or even phrases, which is not surprising. In general, Mongolian is a completely alien language to the Turks. It is a fact.

Translation: From P. Uranbileg and D. Sodnom

The content of the article

MONGOLIAN LANGUAGES, one of the Old World language families. Despite the small number of speakers (about 6.8 million people) and the small number of languages included in the family, their distribution area covers a vast territory from the northeastern provinces of the PRC to the interfluve of the Don and Volga. The Mongolian family includes the following languages.

Mongolian.

This linguonym is used in several senses.

A. In its narrowest sense, it applies to the language of the Mongols of the Mongolian People's Republic, also called after the main dialect Khalkha-Mongolian or simply Khalkha. The Khalkha-Mongolian language has a literary norm and the status of the state language of the MPR; the number of its carriers is approx. 2.3 million (1995). The Khalkha dialect is part of the central group of dialects of the Mongolian language; Along with it, the eastern and western groups are also distinguished. The differences between dialects are mainly phonetic.

B. In a broader sense, the term “Mongolian language” also includes three main dialects (east central and southern, further divided into dialects) language of the Mongols of Inner Mongolia- the autonomous region of the same name and the neighboring provinces of Heilongjiang, Liaoning and Jilin in the PRC, also called Inner Mongolian (view from China) or peripheral Mongolian (view from Mongolia and Russia). The number of speakers of this language (according to the 1982 census) was 2.713 million people; in the 1990 census, the Mongols were recorded together with the Buryats, as well as the Turkic-speaking, but culturally Mongolized Tuvans, as representatives of the “Mongolian nationality” (one of the five main “official nationalities” of the PRC); their total number then amounted to approx. 4.807 million

The differences between the language of the Mongols of the Mongolian People's Republic and the language of the Mongols of Inner Mongolia affect phonetics, as well as such morphological parameters, which are very variable within the Mongolian family, such as a set of participial forms and the presence/absence of some peripheral case forms. The same type of differences exist between dialects within both the Mongolian language of the Mongolian People's Republic and within the language of the Mongols of Inner Mongolia. In reality, it is one language divided by a state border, with many dialects represented on both sides of it. The umbrella term for this is modern Mongolian language; In total, over 5 million (according to other estimates - up to 6 million) people speak it, i.e. more than 3/4 of the entire Mongol-speaking population. About 6 thousand Mongolians live in Taiwan; 3 thousand, according to the 1989 census, lived in the USSR. The division has consequences mainly of an external linguistic nature: the Mongolian People's Republic and Inner Mongolia have different literary norms (in the latter case, the norm is based on the old written language), in addition, the dialects of Inner Mongolia have experienced a noticeable influence of the Chinese language.

B. With an even broader interpretation, the concept of “Mongolian language” expands not only geographically, but also historically, and then it includes the common Mongolian language, which existed until approximately the 16th–17th centuries, as well as Old written Mongolian language- the common literary language of all Mongol tribes from the 13th to the 17th centuries. The dialectal basis of the latter is unclear; in fact, it has always been a supra-dialectal form of purely written communication, which was facilitated by the writing (basically Uyghur) that did not convey the phonetic appearance of words very accurately, leveling out inter-dialectal differences. Perhaps this language was formed by one of the Mongol tribes that were destroyed or completely assimilated during the emergence of the empire of Genghis Khan. It is generally accepted that Old Written Mongolian reflects a more ancient stage in the development of Mongolian languages than any of the known Mongolian dialects; this explains its role in the comparative historical study of Mongolian languages.

The history of written language is divided into ancient (13th–15th centuries), middle (15th–17th centuries) and classical (17th–early 20th centuries) stages. The frequently used terms "Old Mongolian" and "Middle Mongolian" are used to designate the common, although dialectally fragmented, language of the Mongolian tribes of the corresponding historical periods. From the 17th century in connection with the creation of the so-called clear letter by Zaya-Pandita ( todo bichig), adapted to the peculiarities of the Oirat dialects, and the formation of the Oirat literary language, the classical old written Mongolian language began to be used mainly in the eastern part of the Mongolian area - in Khalkha (outer MPR) and Inner Mongolia; In Buryatia, a special Buryat version of the old written Mongolian language gradually formed. In Inner Mongolia, the old written language is still used today. In Buryatia, writing was introduced first on a Latin basis (in 1931), and then on a Cyrillic basis (in 1939); in the Mongolian People's Republic the Cyrillic alphabet was introduced in 1945; New literary languages developed there. In the post-communist MPR, and partly in Buryatia, interest in the old written language is currently being revived; Its teaching is actively carried out.

The language of the monuments of the so-called “square script” of the 13th–14th centuries. due to the presence of a number of structural features, it is sometimes considered as a special variety of the widely understood Mongolian language.

Buryat language

(in the USSR until 1958 it was officially called Buryat-Mongolian). Distributed on the territory of the Republic of Buryatia as part of the Russian Federation, in the Aginsky national district of the Chita region and in the Ust-Ordynsky national district of the Irkutsk region, in a number of villages in the Irkutsk and Chita regions, in two aimags in the north of the MPR and in the Hulunbuir aimag of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in the PRC (the last group is called Bargu-Buryats). The number of ethnic Buryats in the USSR according to the 1989 census was 421,380 people (in the RSFSR - 417,425), of which approx. 363,620 named Buryat as their native language (the rest are mostly Russian-speaking); Mongolia is home to approx. 65 thousand Buryats (1995) and approximately the same number in the PRC (according to 1982 data).

Kalmyk language,

also called Oirat-Kalmyk, and sometimes Mongolian-Kalmyk or Western Mongolian. The most western of the Mongolian languages, it is widespread in Europe, in the Kalmyk Republic - Khalmg Tangch within the Russian Federation, as well as in the Rostov, Volgograd and especially Astrakhan regions. A separate group of Kalmyks who retain their language also lives in Kyrgyzstan in the area of Lake Issyk-Kul. The Kalmyk dialect they use is sometimes called Sart-Kalmak(according to the former name of this group of Kalmyks, numbering, according to 1990, about 6 thousand people; now they are called Issyk-Kul Kalmyks). The other two main dialects of the Kalmyk language are Derbet and Torgut. There is a small Kalmyk diaspora: small groups of Kalmyks live in Taiwan, as well as in the USA and Germany. The number of Kalmyks in the former USSR in 1989 was 173,821 people, of which 156,386 called Kalmyk their native language.

Kalmyks are descendants of the Oirat tribes who migrated to the right bank of the Volga from Dzungaria (northwest China) in the 17th century. and adopted a self-name Kalmyk; they began to call their language Kalmyk ( halmg kel). The Oirats who remained in Dzungaria were by the mid-18th century. almost completely exterminated by the troops of the Chinese Qing Empire, but some Kalmyks returned at the end of the 18th century. to Dzungaria, where (in the west of the MPR and in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the PRC) their descendants live to this day; in the PRC they are called Oirat tribes (139 thousand people according to 1987 data), in the MPR they are simply called Oirats (205 thousand). The language of the Oirats of the MPR and the PRC is indicated in the literature somewhat vaguely; some authors call it Kalmyk, others, without directly naming the language, talk about Oirat dialects (Torgut, Derbet, Bait, Uriankhai and some others; there is also the Torgut-Olet dialect of the Oirats, who migrated in the 17th century to Lake Kukunar in the Chinese province of Qinghai ; sometimes it is even considered a separate language); dialects are counted from literary Oirat language, which arose in the 17th century. and used by the Kalmyks of Russia until 1924 and by the Kalmyks of the Mongolian People's Republic until 1946 (in Xinjiang it is still used today).

Bao'an language,

which, according to 1990 data, is spoken by approx. 12 thousand people (Muslims, unlike the majority of the Mongolian peoples) in the PRC - in the Baoan-Dongxiang Autonomous County of the Linxia Autonomous Prefecture of Gansu Province (Dahejia dialect, about 6 thousand people) and in Tongren County in Qinghai Province (Tongren dialect, about 4 thousand people; the Mongors living in Gansu also use the Tongren dialect to communicate with the Baoan). There are noticeable differences in phonetics and vocabulary between dialects; The Dahejia dialect was influenced by the Chinese, and the Tongren dialect by the Tibetan languages. Bao'an is an unwritten language used in everyday life; Chinese writing is used for written communication.

Dagursky

(also Daurian, or Dahurian) a language whose speakers have long lived in two geographically distant regions of the PRC: in Heilongjiang province (Qiqihar and surrounding counties - the very center of historical Manchuria) and Hulunbuir aimag of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region in the northeast country and in Chuguchak County of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in the far northwest, near the border with Kazakhstan. The number of ethnic Dagurs according to the 1990 census is approx. 121 thousand people, of which approx. 85 thousand speak Dagur language (usually also Chinese). The ethnic origins of the Dagur are unclear; Some researchers consider them to be a Mongolian tribe that was subject to strong Tungus-Manchu influence, others - a Tungus-Manchu tribe that passed into the 13th–14th centuries. into Mongolian language. Four dialects are distinguished: Butkha, Tsitsikar, Hailar (in which such a strong Tungus-Manchu influence is seen that it is sometimes even considered a dialect of the Evenki language) and Xinjiang. The language is unwritten, although attempts to introduce writing have been made repeatedly, starting from the Qing time; experimental writing was created once on a Cyrillic basis and twice on a Latin alphabet (in the 1920s and 1960s). For the purpose of written communication, the Manchu language was previously used, and now Chinese is used. The number of borrowings from the Tungus, Manchu and Cathay languages is also large. In functional terms, the language performs purely colloquial and everyday functions.

Dongxiang language

(occasionally also san(b)that- by the name of the ethnic group), widespread in the southwest of Gansu province in the People's Republic of China, in the Bao'an-Dongxiang Autonomous County of the Linxia Autonomous Prefecture (in the neighborhood of the Bao'an language, with which we are partially intelligible; like Bao'an, Santa are Sunni Muslims). The number of speakers (according to the 1990 census) is approx. 374 thousand. Dialect division, according to B.Kh. Todaeva, is not expressed; according to other sources, there are three dialects with minor differences. The language is unwritten; used only in everyday life; the younger generation in a number of situations uses Chinese even when talking to each other; in the dictionary - about 30% of Chinese borrowings.

Mongolian language

(aka that– by the name of the ethnic group – or Shirongol-Mongolian), common in the east of Qinghai province (in Huzu, Minghe, Datong and Tongren counties) and in Gansu province in China. The number of speakers (according to the 1982 census) is 90 thousand. There are two very different dialects: Hutzu (60 thousand; divided into subdialects, used in the county of the same name and in Datong county) and Minghe (30 thousand speakers). In Tongren County, Mongors often use the Bao'an language to communicate with the Bao'an. The language is unwritten; For written communication, educated Mongors use Chinese and Tibetan, which have had a certain influence on Mongorian, including in phonetics. Most of the population, however, speaks Chinese poorly.

Mughal language,

which was considered endangered already in the 1950s; Currently, it is reportedly spoken by approx. 200 people (representatives of the older generation) from several thousand scattered Mongol groups in Afghanistan - primarily in the villages of Kundur and Karez-i-Mulla near Herat. Native speakers of the Mughal language also speak New Persian; ethnic Mughals in northern Afghanistan speak Pashto. The Mughals consider themselves descendants of the Mongol warriors of the 13th century who settled in Afghanistan. The language is unwritten; used within the family circle and partly as a secret language; There are examples of his writing in Arabic writing, including texts of the poet’s poems from the early 20th century. Abd al-Qadir, who wrote in the Mughal language.

Shira-Yugur language,

spoken by some of the people Yugu(aka Yellow Uighurs; the name “Yugu” has been adopted in the PRC since 1954), living in the north-west of Gansu province in the PRC. The total number of Yugu – St. 12 thousand people, of whom the Shira-Yugur language is spoken (according to 1991 data) approx. 3 thousand people (“Eastern Yugu”). According to some assumptions, the Shira-Yugurs are a Turkic tribe that switched to the Mongolian language. (Another approximately 4,600 people in Sunan Autonomous County speak the Turkic Saryg-Yugur language; they are called “Western Yugu.”) Both language names are derived from the name of the people, meaning “yellow Uighurs.” For a slightly smaller part of the population, the native language is Chinese, which is also used as a lingua franca; And some of the Yugu speak Tibetan. The language is unwritten; Yugu use Chinese for written communication.

In addition to those listed, two more dead languages are classified as Mongolian.

Khitan language

- language Khitan, or Chinese; It is believed that the Russian name for China comes from the name of this not-at-all-Chinese tribe. The Khitans were part of a tribal union that captured the country at the beginning of the 10th century. Northeast China and founded the Liao Empire. In 1127 it was defeated by the Jurchens, after which part of the Khitans migrated to the west, to Semirechye (southeast of modern Kazakhstan), where they retained statehood until the invasion of Genghis Khan in 1211. Modern Dagurs consider themselves direct descendants of the Khitans. The belonging of the Khitan to the Mongolian peoples and the Khitan language to the Mongolian people is established with sufficient confidence on the basis of data from Chinese historical treatises, which include a number of Khitan words and words in Chinese transcription, as well as information about Khitan syntax (typically Altai). The Khitans used two writing systems: the “big letter”, which was not particularly widespread (apparently, purely ideographic), and the “small letter”, invented a little later, in 925, structured like Chinese and allowing both ideographic and phonetic use of signs, outwardly similar to Chinese characters. Efforts to decipher the “small letter”, preserved in not too numerous epigraphic monuments, have been going on for several decades and are gradually bringing some results; however, it is too early to talk about confident decryption.

Xianbei language

– tribal language Xianbi, who lived in the 2nd–4th centuries. on the territory of modern Inner Mongolia, which, together with the Mongolian Tabgachi tribe, conquered China in the 4th century. and founded the “Late Wei” Toba dynasty, which lasted until the mid-6th century. The extremely limited information contained in Chinese sources allows Xianbei to be classified as a Mongolian language, and Tabgach to be considered as its dialect. The Syanbi, according to some assumptions, had a writing system based on the Orkhon-Yenisei runic alphabet.

Despite the small number of Mongolian languages, several of their classifications are presented in the literature. One of them, belonging to G.D. Sanzheev, divides the living Mongolian languages - without taking into account the old written Mongolian - into the main ones (Mongolian proper, Buryat and Kalmyk; these languages throughout their history formed a relatively single mass and were in close contact; they all have a literary tradition, until recently common; and all currently enjoy state status - in Mongolia, Buryatia since 1992 and Kalmykia since 1991) and marginal (or “island” - all others, separated from the main Mongolian massif by a foreign language environment - Chinese, Tibetan, Iranian; all of them are unwritten and have a low sociolinguistic status; the number of speakers of the Dongxiang language, for example, is comparable to the number of Buryats or Kalmyks/Oirats). T.A. Bertagaev’s classification is also widespread, based on phonetic parameters: the presence or absence of synharmonism (similarity of vowels in root vowel suffixes), and the disappearance or preservation of the initial *f. This classification distinguishes a group of anlaut-vocal languages (with synharmonism and the disappearance of the initial *f; it coincides with the group of “main” Mongolian languages), a group of anlaut-spirant languages (without synharmonism and preserving the initial *f in the form of one or another fricative consonant-spirant; this group includes all other languages except Mughal); and a mixed group consisting of only the Mongolian language, which does not have synharmonism, but has not retained the initial spirant (the ancient Mongolian written language and the language of “square writing” belong to the same group). There are also more detailed classifications that divide the “main” and sometimes “island” groups.

The time of divergence of the dialectally fragmented but unified Mongolian language dates back to the 16th–17th centuries; in other words, according to standard comparative criteria, this is not a family, but a group of languages, moreover, very closely related (like the Tungus-Manchu languages). The similarities between the “main” Mongolian languages are especially great, further supported by the presence of a common supra-dialectal written language. The “island” languages, under the influence of the foreign language environment and in isolation from the Mongolian “core,” underwent more dramatic changes. Nevertheless, the term “family” is more often used to designate Mongolian languages, which is facilitated by the lack of general acceptance of the Altai hypothesis ( cm. ALTAI LANGUAGES), postulating the historical community of the Turkic, Mongolian and Tungus-Manchu languages (and also, in accordance with the increasingly popular point of view, the Korean and Japanese languages), and the long-standing tradition of calling the Turkic languages \u200b\u200bin a "family" (in any relation to Altaic hypothesis) has the same position in the genealogical classification as the Mongolian and Tungus-Manchu languages. Due to these considerations, the Altaic languages are often spoken of as a “macrofamily,” although the degree of their divergence is in no way stronger than in the Indo-European family of languages, and certainly less than in such a classical macrofamily as Afroasiatic.

The Mongolian languages are very close and have much in common with the languages of other groups of the hypothetical Altaic family, especially with the Tungus-Manchu.

The phonological systems of Mongolian languages are relatively simple. In the vocalism of most languages, seven vowel phonemes are distinguished: the same five as in Russian, plus labialized front (in Kalmyk) or middle (in other languages) vowels (such as German ü And ö ; in Cyrillic scripts they are designated Y And q respectively). The Mongolian, Bao'an and Mughal languages and the Central Mongolian dialect of Inner Mongolia do not have these vowels. In most Mongolian languages, there is a phonemic (meaning-distinguishing) opposition between short vowels and long vowels of similar quality (which appeared after the disappearance of the intervocalic consonant - cf., for example, modern Mongolian. baatar"hero, knight" and earlier bag atur, borrowed from Turkic languages? – as in Russian, where the back-lingual consonant is preserved). In Cyrillic graphics, this opposition is conveyed by doubling the sign for the vowel, for example. Boer. borough"grey" - borough"rain"; Gehe"speak" - geehe"lose" etc. In Mughal and Dongxiang there are no long vowels; in Bao'an and Shira-Yugur the contrast between long and short vowels is non-phonemic. The stress is dynamic, in most languages it falls on the first syllable, and in Mongolian, Baoan and Shira-Yugur it falls on the last. Unstressed vowels are usually reduced (as in Russian), the reduction is especially strong in Kalmyk, where it is reflected in spelling - cf., for example, the name of the Kalmyk Republic, in spelling notation Halmg Tankhch, in Russian transcription [halmъг tanhъчъ], where a hard sign denotes a reduced sound. In languages with final stress, as a result of reduction, syllables of the SSG structure, which are not characteristic of Mongolian languages as a whole, appear. In Mongolian and Buryat, synharmonism is presented in row and roundness, in Kalmyk only in row; in other languages, synharmonicism is absent altogether or is greatly destroyed.

Consonantism (from the point of view of a native Russian speaker) is simple; among the relatively “unusual” sounds there are voiced africates dñ And dz(in particular, in Mongolian, where in spelling they are designated by letters and And h, because there are no corresponding fricatives in Mongolian), a voiced velar spirant g(in Kalmyk; however, this sound is also represented in southern Russian dialects, in the Ukrainian language and in the standard pronunciation of indirect cases of the word God in Russian literary language), glottal spirant h(in Dongxiang, Baoan, Buryat). In Buryat, all affricates, including voiceless ones, have become the corresponding fricatives (i.e. and, h, w, With).

The features of the “Altai type” (a term fraught with confusion of typological and genealogical categories and therefore long considered incorrect, but now, with appropriate reservations, actually rehabilitated) are especially clearly manifested in the grammar of the Mongolian languages. All of them are agglutinative, i.e. used to express inflectional and word-forming meanings of chains of relatively unambiguous and unchangeable or weakly and regularly modified affixes: bur. bari-gda-ha-g y"not to be caught" where bari-"grab, -when-"passive voice indicator" -Ha-“indicator of the participle of the future tense” (in Mongolian languages it also serves as an infinitive) -g y"absence rate". Affixes are located after the root, i.e. are suffixes. Definition of any type (Mong. ahyn ger "brother's house/yurt", lit. "brother's house/yurt", modon ger"wooden house", Tsagaan ger"white house/white yurt") is located in front of the designated one. Instead of prepositions, postpositions are used (Mong. Garyn Dor"under the house") The word order in a sentence is SOV, i.e. “subject – object – predicate”; the syntactic structure is nominative-accusative, as in Russian ( cm. LINGUISTIC TYPOLOGY). To express various relationships between predications in a complex sentence, a developed system of impersonal verbal forms is predominantly used - various participles and gerunds, often with a postposition; In such forms, the word denoting the subject of the action can appear in indirect cases: Mong. Delhiy bqq rq nhiy bolokh tuhay bagsh tailbarlan yarzhee“The teacher explained that the Earth is a sphere,” lit. “The earth is round, the teacher said while explaining”; Namaig gertee kharval oroi bolson“When I returned home, it was already late,” lit. "I-blame. Case in-my-house, when I returned it was too late." There are few original unions; words that perform conjunction functions are often grammaticalized verb forms (for example, Mong. ahoul, more"if" from archaic verbs of being A- And bts-; AVH And bolovch“although” is a form of concessive gerundial participle from the same A- and from modern bolokh"to become", derived from bts-; gezh“what” is a form of connecting gerund from modern. geh"to speak") The interpretation of the corresponding syntactic phenomena remains a subject of debate.

The Mongolian languages have a completely traditional set of parts of speech, which are further grouped into three classes: inflected, conjugated and invariable. Nouns have different number forms (singular and plural); There are several indicators of the plural in most Mongolian languages, and they are used only when necessary to indicate plurality. Case forms from seven to nine; in all languages (except Dongxiang and Baoan, where there is no joint case, but there is a connective) there are indicators of the genitive, dative-local, accusative, initial (movement from the subject), instrumental and joint cases; Some languages have additional forms or overlaps of case forms. The status of the nominative case is a matter of debate; a noun in the stem form can perform various functions - subject, modifier, object and nominal part of the predicate; in the last three cases, this form often (but not always) indicates an uncertain name. The double declension is quite widespread: Mong. bagsh-iin-d“at the teacher (in the house)” or “to the teacher (home)” – the indicator of the genitive case is followed by the indicator of the dative-local case. In most Mongolian languages, the name takes postpositive indicators of personal (as in Turkic) as well as reflexive possessiveness; they are placed after the case indicator. The adjective does not change (there are no degrees of comparison, in particular) and is weakly separated from the noun. Personal and demonstrative pronouns have different stems in the nominative and indirect cases, for example, mong. bi"I", mini"me" (gen. fall.), Namaig“me” (vin. pad.), etc.; Demonstratives are used as personal pronouns of the 3rd person in all languages except Dagur, Dongxiang, Bao'an and partly Mughal. The categories of gender/class and animacy inherent in many languages of the world are absent, which is not only a common Altai, but also a common Ural-Altai feature. There is some semblance of the category of genus in the system of Mongolian word-formation suffixes denoting the color and age of animals, for example. Mong. gunan"three-year-old" – gunzhin"three-year-old"

The verb has a developed system of personal (finite) and impersonal (non-finite: participles and gerunds) forms. There are more non-personal forms in Buryat and Mongolian; in the latter, for example, there are four to six types of participles and about one and a half dozen gerunds - some of them are morphologically non-elementary and therefore can be interpreted differently. The abundance of non-finite forms is a characteristic feature of the Mongolian languages (and makes them similar to the Tungus-Manchu languages), and their intensive use is a characteristic feature of the Mongolian syntax. All verb forms have a voice category (impellative or causative voice is represented, and in most languages also passive, joint and reciprocal; voice suffixes in all languages except Bao'an can be combined with each other, for example, Mong. baiguulagduulakh“to give in to organization”: two indicators of the incentive voice and one indicator of the passive voice). The participial and finite forms express the category of tense, intertwined with the category of the method of verbal action. Most languages have more than one form for action in the past, while present and future tenses are not distinguished in all Mongolian languages (in particular, there is one form for future and present in Mongolian and Kalmyk). The picture is complicated by the fact that the function of the predicate can be (and, for example, in Mongolian it often is) a participle. Almost all past tense forms are used interchangeably, and the relationships between them are unclear. Personal forms also have a category of mood. In addition to the indicative, there is a warning ( es haruuzai“I’m afraid they won’t see”) and several moods of the imperative-desirable type, distinguishing quite a few different forms of politeness (in which one can see an areal feature - “Far Eastern politeness”, which found its expression in a special grammatical category in the Japanese language). Different negative particles are used with different verb forms and forms of different moods. Analytical verb forms are quite widely represented, conveying subtle shades of verbal action.

There are few adverbs in Mongolian languages; many of them are grammaticalized case forms of nouns.

A feature of the Mongolian languages is the intensive use of various kinds of discourse particles, the patterns of which are not sufficiently described.

The syntax of the Mongolian languages is basically common Altaic and was briefly described above.

In the vocabulary of Mongolian languages, there are numerous productive word-formation processes (suffixal word formation, stem formation), which allowed those of these languages that fully perform all sociolinguistic functions to develop national terminological systems. This applies to the greatest extent to the Khalkha-Mongolian language; In Kalmyk and Buryat, borrowings from Russian were also very intense, which was facilitated by the massive bilingualism of the Buryats and Kalmyks. Some borrowings from Russian were carried out orally and therefore reflect Russian pronunciation (rather than spelling), moreover, adapted to the phonetics of the corresponding languages (Burgian spelling: araadi"radio", tooshho"point (trading)", humpeet"candy", peeshen"bake", Iristraan"restaurant" etc.; the transmission of Russian stress using longitude is typical), others were borrowed in a form close to Russian spelling. The actual pronunciation of both depends on the speaker’s degree of knowledge of the Russian language, as well as on the cultural attitude: in modern Russian, the reproduction of English pronunciation is considered at least a mannerism, worthy only of leading FM radio stations, while in Buryatia, the reproduction of Russian pronunciation is at least to a certain extent was welcomed. The Mongolian languages also have a vast layer of borrowings from the Tungus-Manchu languages (which are not always easy to separate from parallels, apparently due to linguistic kinship), numerous borrowings from Tibetan and Sanskrit, Chinese (the latter are especially numerous in the “island” Mongolian languages , widespread in the territory of the People's Republic of China), to a lesser extent, Persian and Arabic.

Mongolian borrowings in Russian are few; Most of the “nomadic” vocabulary in the Russian language is actually Turkic in origin, although sometimes it has Mongolian correspondences. In reality, Mongolian borrowings came mainly from the “near” Kalmyk language at a relatively later time, for example doha, malachai. Such exoticisms as aimag(name of administrative unit in Mongolian-speaking countries), lama And datsan(Lamaist monastery; both words, in turn, came to the Mongolian languages from Tibetan), Burkhan“god, spirit” – from the name of Buddha; this word came to the Mongolian languages through the Chinese language; about(a pyramid of stones in a particularly prominent place, for example on a pass, serving as an object of worship).

Throughout their history, the Mongols created for themselves (by adapting existing writing systems) many different scripts. The earliest of them, apparently, was the Orkhon-Yenisei runic writing used by the Syanbi. By the 10th century include monuments of the “large” (hieroglyphic) and “small” (mixed and in some ways, perhaps even sound) Khitan writing. At first, the Uyghur language and Uyghur script were used in the offices of Genghis Khan. In 1269, the Tibetan-based syllabary “square” letter, or passepa (otherwise Pakba, which more accurately conveys its Tibetan name), developed by the great Lama Pakba (this title means “worthy”) Locho Gyachan, was adopted. The Pakba letter very accurately conveyed the features of the language of the then Mongolian elite, which made it tied to the features of one of the dialects; besides, it was quite complex (as, indeed, the Tibetan writing itself). They have been using it for about a hundred years. Between 1307 and 1311, Lama Choji Odser, based on the Uyghur script, developed the Mongolian vertical script, which became the main means of writing Mongolian speech; In Inner Mongolia, this alphabet is still used in practice today, and it has not been forgotten in other countries. Odser's alphabet ignored many phonetic differences and, as such, was always compatible with various dialects of the Mongolian language (later with various languages); Moreover, it is simple in style and convenient for cursive writing. Subsequently, a transcription alphabet was created based on this alphabet galik for recording foreign words; his signs are also used to this day. In 1648, Lama Zaya-Pandita Namkaidzhamtso created a modification of the vertical script for the Oirats, and in 1910, Lama Agvan Dorzhiev developed a similar modification for the Buryat language; but the transition to the Latin alphabet and then to the Cyrillic alphabet soon became on the agenda. In 1686, the syllabic horizontal-square script Soyombo was also developed; There were other experiments in the written recording of Mongolian speech (syllabic Tibeto-Mongolian writing and Turkic Brahmi, sound Manchu-Mongolian and Arab-Mongolian, etc.), but they did not receive any wide distribution.

The earliest surviving monument of the Mongolian languages (except for the still far from final decipherment of the Khitan script) is Chinggis Stone beginning of the 13th century with an inscription carved on it. By the 13th century. include monuments of folk poetry ( Hongirad song, Song of Bohe-Chigler). The literature of subsequent centuries was also mainly of an epic nature. There is also a huge volume of Lamaist literature, which has occupied a dominant position since the 17th century, and treatises on various branches of knowledge. Literature of a secular nature begins to develop again in the 19th century; The modern stage of development of literature in Mongolian languages dates back to the beginning of the 20th century.

The study of Mongolian languages has a long history; the learned monks were familiar (through Tibetan media) with the powerful Indian linguistic tradition; in the 17th–18th centuries. Sanskrit grammatical treatises were translated into Mongolian, including the famous grammar of Panini. Dictionaries and manuals on the Tibetan and Mongolian languages were created. In the West, the first studies on Mongolian languages appeared in Russia in the first half of the 19th century; however, already in 1730 F. Strahlenberg included in his Geography small Kalmyk-Mongolian dictionary. Important stages were the Mongolian grammars of J. Schmidt (1832), O.M. Kovalevsky (1835) and especially A.A. Bobrovnikov (1847) and the Kalmyk grammar of A.V. Popov (1849). From the second half of the 19th century. the comparative historical study of Mongolian languages began (works by M.A. Castren, later by A.D. Rudnev, V.L. Kotvich, G. Rastedt, B.Ya. Vladimirtsov, N.N. Poppe, G.D. Sanzheev) ; in parallel, descriptive work continued (research by T.A. Bertagaev, Ts.B. Tsydendambaev, M.N. Orlovskaya, G.Ts. Pyurbeev and others, as well as Mongolian scientists - Ts. Damdinsuren, S. Luvsanvandan, A. Luvsandendev) . An important role in the 1950s was played by B.Kh. Todaeva’s field research on the “island” Mongolian languages of the PRC. Research on Mongolian languages is actively developing in the Mongolia, Buryatia and Kalmykia, as well as in Hungary, Germany, the USA, and Japan. Detailed grammatical descriptions of almost all Mongolian languages have been created; The “main” languages have been and continue to be studied in great detail, and detailed dictionaries have been compiled for them (for example, Buryat-Russian dictionary K.M.Cheremisova 1973 was recognized as one of the best national-Russian dictionaries in the USSR), textbooks were written. Many universities around the world are training Mongolian scholars.

Pavel Parshin

Literature:

Sanzheev G.D. Comparative grammar of Mongolian languages. M., 1953

Todaeva B.Kh. Mongolian languages and dialects of China. M., 1960

Sanzheev G.D. Comparative grammar of Mongolian languages. Verb. M., 1963

Sanzheev G.D. Linguistic introduction to the study of the history of writing of the Mongolian peoples. Ulan-Ude, 1977

Vladimirtsov B.Ya. Comparative grammar of written Mongolian language and Khalkha dialect, ed. 2. M., 1989

Mongolian languages. Tungus-Manchu languages. Japanese language. Korean. – In the book: Languages of the world. M., 1997

Hello, dear readers – seekers of knowledge and truth!

Interestingly, the Mongolian, Chinese, Afghan and Russian populations have something in common. And, oddly enough, it’s language. After all, Mongolian is spoken not only in Mongolia - there is a whole language group that has spread far beyond its borders.

We want to tell you what the Mongolian group of languages is. From the article you will learn what families and groups of languages there are, what place Mongolian occupies among them. Their geography, types, features, history - we will talk about all this below.

Language families

Each language acquires connections with other, related ones. Historically, they are due to the proximity of peoples and origin from the same proto-language. Related to this is the concept of genealogical linguistic classification.

There are more than seven thousand languages in the world.

Of course, it is difficult to list them all in a group. Therefore, we will provide only a list of the main language families, each of which is divided geographically into groups, and then into individual languages and dialects.

Language families are distinguished:

- India, Europe - the Indo-European family is considered the largest;

- Caucasus;

- Africa, Asia;

- China, Tibet;

- Ural;

- Altai.

The Mongolian group is included in the Altai family according to the Altai theory, which is considered the main one. This also includes the Chinese-Tibetan, Turkic, and Far Eastern groups.

Geography of the Mongolian language

The Mongolian peoples settled mainly in Asian and European territories: in the steppes, forests, mountains, and near the seas. For the most part, these are the lands of the Republic of Mongolia, Afghanistan, northeast China, especially Inner Mongolia, as well as some Volga and Baikal republics in Russia - Buryatia, Kalmykia, Tuva.

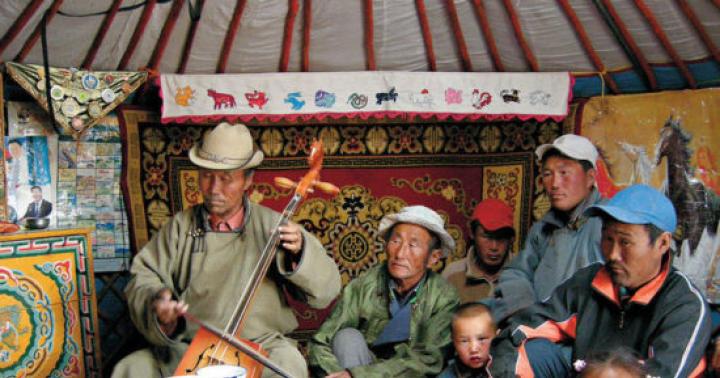

In a Mongolian yurt

In a Mongolian yurt

However, many representatives of the Mongolian people live far from these territories, while maintaining their own traditions, including their language.

The Mongolian group includes several languages that are very similar in vocabulary, grammar, and sound. This state of affairs is not surprising - until the 5th century they were united and only later split into several branches.

They are closely intertwined with Turkic, Tungusic, Manchu, Tibetan, Korean, and Slavic languages, because their speakers live next door. Linguists note especially many borrowings from Turkic. Even now there are people here who speak two languages at once - the so-called bilinguals, for example, Uyghurs and Khotons.

Classic Mongolian was used by all literate Tuvans until the 40s of the last century.

The number of speakers of Mongolian languages in the world exceeds six million. They are divided into dialects of the west, center, and east. Their differences mostly relate to phonetics and pronunciation.

Tyva

Tyva

Mongolian is recognized as the official language in Mongolia. It began to take shape in this capacity after the internal revolution of 1921. The Khalkha dialect of the Central Mongolian subgroup was taken as a basis - laws are passed in it, books are written, and educational programs are built.

Inner Mongolia, an autonomous region of China, does not have a distinct dialect, so its residents use the classic old script.

Kinds

Defining a clear classification of languages seems difficult. Conventionally, they are divided into two large groups – northern and southern.

Northern group includes:

- Old written

Connected with the history of the 13-17th centuries, it incorporates the Middle Mongolian, Buryat version, today’s literary language of Inner Mongolia.

- Central subgroup

This includes modern Mongolian: the state language of Mongolia is Khalkha, dialects of the center, east, south, which belong to the Mongol-Chinese territories, as well as the Ordos branch. In addition, Buryat and Khamnigan, known in the Russian Transbaikalia, are included in the central cluster.

- Western cluster

Covers Kalmyk, Oirat and their dialects.

Kalmyk camel

Kalmyk camel

The southern group includes the following languages:

- Shira-Yugur - spoken by the Yugu people in China;

- Mongolian – covers the Chinese provinces of Qinghai and Gansu;

- Bao'an - has about 12 thousand Chinese speakers, whose main feature is the Muslim faith;

- Dongxiang - also common in several Chinese provinces, covers more than 350 thousand people;

- Kangjia.

In addition, there are other major languages:

- Mughal - common in Afghanistan;

- Khitan - common among the Khitai tribe who lived on Chinese territory in the 10th century; It is believed that thanks to this name, “China” sounds exactly like this in Russian;

- Dagur - native to the Dagur people of the People's Republic of China;

- Xianbi - refers to the ancient Xianbi tribe, which lived in the 2nd-4th centuries in what is now Inner Mongolia.

Yurts in Inner Mongolia

Yurts in Inner Mongolia

All these languages, common among certain nationalities, in certain countries, regions, provinces, have their own dialects. Due to their similarity and common origin, representatives of the Mongolian peoples can communicate without problems, especially if they live in adjacent territories.

At the same time, some of them have such different features of vocabulary, pronunciation, formation of gerunds, and cases that their representatives are unlikely to understand their “relatives.”

One of the problems of modern Mongolian languages is the threat of extinction of some of them.OngoingGlobalization with the Internet, television, world trade, mass communications puts Khalkha in first place - it is used by 8 out of 10 speakers. At the same time, the languages of small nations are gradually forgotten.

Features of the language

Mongolian languages are considered quite complex. Many of them have common features:

- agglutinativeness - prefixes and suffixes are “built on top” of one another, which changes the meaning of the word;

- inflectivity – play a big role word endings. For example, they completely replace personal pronouns;

- strict word order - first comes the dependent word, containing, for example, a description of place or time, and at the end - the main word;

- ergativity is a case indicating the subject and object of an action, the Russian equivalent to it is the passive voice of participles;

- a small number of parts of speech - there is only a verb (can be conjugated), a name (can be inflected), unchangeable parts of speech. A noun differs from an adjective only syntactically;

- presence of singular and plural;

- 7-9 cases – the number depends on the specific language;

- participle, participle as special forms of the verb;

- verb tenses - the past tense can be expressed by several forms of the verb at once, while the present and future can be the same;

- cautionary mood - it exists along with the motivating and indicative, expressed in phrases like “I’m afraid that...”.

Buryat holiday

Buryat holiday

Alphabet

Initially, they wanted to make the alphabet based on the Latin alphabet. However, as a result, the Cyrillic alphabet was taken as a basis - in 1943 the alphabet was officially adopted.

It contains 35 letters. In addition to the letters familiar to Russian people, two more vowels are added here - ө, phonetically reminiscent of the German ö, and ү, pronounced like the German ü.

The remaining letters sound the same as in Russian. The only exceptions are the complex names of some of them:

- y – khagas i;

- ъ – khatuugin temdeg;

- y – er ugiyn y;

- ь – golden temdeg.

This alphabet is still used today.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I would like to say that Mongolian languages are unique and amazing. They are spoken by about 6 million people - not so many on the scale of a planet of seven billion.

The general group is divided into many dialects, each of which has its own characteristics. Of course, we would like all of them to be preserved despite globalization, and for our descendants to also be able to learn about the culture and depth of the soul of these peoples through the study of linguistics.

Thank you very much for your attention, dear readers! We hope you found our article useful and you were able to get a little closer to understanding the features of the Mongolian world. If you liked the information, share it with your friends by providing links to the article on social networks.

And join us - subscribe to the blog to receive new interesting articles in your email!

Mongolian languages are a group of languages of the Mongolian peoples. The total number of speakers is 6.5 million people. The question of including this group in the Altaic languages remains at the level of hypothesis. Mongolian languages are the result of the development of dialects of the once unified (until the 16th-17th centuries) Mongolian language; they are divided into the main ones - the Mongolian language proper, the Buryat language, the Kalmyk language, and marginal ones - Mughal (in Afghanistan), Dagur (in Northeast China ), Mongorian, Dongxiang, Baoan and Shira-Yugur (in the Chinese provinces of Gansu and Qinghai). For major Mongolian languages from the 13th century. until the beginning of the 20th century. (Kalmyk language - until the middle of the 17th century) a single old written Mongolian language was used, which continues to be used in Inner Mongolia (PRC). Marginal languages were heavily influenced by Iranian dialects, Tibetan and Chinese.

The main Mongolian languages are phonologically synharmonic, and in grammatical structure they are suffixal-agglutinative, synthetic. The vowels of modern Mongolian languages - various reflexes of 4 ancient back rows (a, o, u, ы) and 4 front row ones (e, e, Y (ÿ), i) - are quantitatively and phonologically divided into short, long and (absent in Kalmyk language) diphthongs. Consonants go back to the ancient b, m, n, t, d, ch, j, s, l, p, k, g (as well as “k” with allophones of the back tongue and velar), ң, and also (?), p, w that have undergone evolutionary changes. Significant differences in phonetics between the main Mongolian languages: the dialects of Inner Mongolia do not have the sibilant affricates ts, dz, which exist in other Mongolian languages and dialects. Mongolian languages proper are characterized by the presence of aspiration of strong consonants and regressive dissimilation of initial strong ones, which is not found in other Mongolian languages. The Kalmyk language has vowels o, ө, e only in the 1st syllable, while other Mongolian languages are characterized by labial harmony; in addition, in this language there are phonemes ə (like Finnish ä), the front row of the lower rise, flowing ђ (orthographically h) and stop “g” (in other Mongolian languages, allophones of one consonant phoneme “g”). The Buryat language has a glottal h (< с), отсутствуют аффрикаты ч (>w), j (> f, h). In addition, in Buryat and many Mongolian dialects proper, the ancient back-lingual allophone "k" is reflected as the spirant "x", but is preserved in the Kalmyk language and some internal Mongolian dialects. All Mongolian languages have long been distinguished by the fact that the consonants r, l (with a few exceptions) and, prevocalically, ң do not occur at the beginning of a word; at the end of a syllable, voiced consonants are deafened (much like in Russian); strong consonants, affricates j (Buryat “zh”), dz (Khalkh., but Buryat. and Kalm. “z”), ch (sh), c (Khalkh., Kalm., but Buryat. “s”) not may be at the end of a syllable if the final vowels are not dropped; a confluence of consonants is possible only at the junction of syllables. Deviations from the stated norms can only be in borrowed words. In the major Mongolian languages, consonants can (but not always) be palatalized or non-palatalized phonemes.

The main Mongolian languages are grammatically very close to each other. These languages traditionally have the same parts of speech as European ones. But some Mongolists, in the category of names, distinguish subject names, in the infinitive position corresponding, for example, to Russian nouns, and in the defining position to adjectives (Mongolian temer biy “there is iron”, but temer zam “railway”), and qualitative names corresponding to Russian nouns, qualitative adjectives and adverbs of manner of action (morina khurdan ni “fastness of a horse”, khurdan mor “fast horse”, khurdan yavna “walks quickly”).

Any word consists of a root, derivational and inflectional suffixes. The root can either be dead (for example, tsa-< *ча- в словах цагаан «белый», цасан «снег», цайх «белеть», «светать») либо живым (напр. гэр «юрта», гар «выходи»). Живой корень служит базой словообразования и словоизменения, мертвый образует первичную грамматическую основу, принимая соответствующие словообразовательные суффиксы. От первичной основы могут образовываться вторичные, третичный и т.п. основы с последовательным рядом суффиксов: ажил «работа», ажилчин «рабочий», ажилла- «работать», ажиллагаа «деятельность»; ял- «победить», ялалт «победа», ялагд- «быть побежденным», ялагдал «поражение».

A nominal stem is a form of the nominative case (exceptions are the stems of personal pronouns), to which plural suffixes are added. number, other cases and possessiveness (personal, impersonal, reflexive), for example nom “book”, nomud “books”, nomudaar “by books”, nomudaaraa “by your books”, nomudaar chin “by your books”. The latter are located after the case suffix. The Mongolian language has 7 cases (in the Kalmyk and Mongolian dialects of the Ordos type there is also a connective case): nominative, genitive, accusative, dative-local, initial and instrumental; in the old written Mongolian language there is also a locative case in -a//-e (only in names with a final consonant).

The verb stem is the imperative form of the 1st person singular, from which all other forms of the verb are formed: 8 imperative-desirables, which cannot be used in interrogative sentences and can only be accompanied by their inherent particles of negation-prohibition “bitgiy” and “bu” (in the Kalmyk language “biche”) - “not”, 4 indicative, 5 participial and 12 participial (3 accompanying and 9 adverbial). Verb systems have 5 voices (direct, incentive, passive, joint and reciprocal), the suffixes of which are located between the primary stem, the direct voice form and any other conjugated form of the verb or any derivational suffix. In Mongolian languages there are single relict forms of the exclusive 1st person plural pronoun.

Syntactic features: SOV or OSV word order, subject and modifier respectively precede the predicate and the modifier. When there is a quantitative definition, what is being defined most often remains in the singular form. Of the homogeneous members of the sentence, the last one receives formalization (the so-called group declension). The definition does not agree with the defined either in number or in case. From the beginning of the 13th century. Mongolian writing is known. In the 20-40s. 20th century the main Mongolian languages switched to new alphabets based on Russian graphics.

Literature

Vladimirtsov B.Ya. Comparative grammar of the Mongolian written language and the Khalkha dialect. L., 1929.

Sanzheev G.D. Comparative grammar of Mongolian languages, vol. 1. M., 1953.

Sanzheev G.D. Comparative grammar of Mongolian languages. Verb. M., 1964.

Todaeva B.Kh. Mongolian languages and dialects of China. M., 1960.

Bertagaev T.A. Vocabulary of modern Mongolian literary languages. M., 1974.

Poppe N. Introduction to Mongolian comparative studies. Helsinki, 1955.

G. D. Sanzheev

MONGOLIAN LANGUAGES

(Linguistic encyclopedic dictionary. - M., 1990. - P. 306)

Mongolia Mongolia

Regional language:

China China: Inner Mongolia

Russia Russia: Buryatia; Kalmykia; Irkutsk region: Ust-Ordynsky Buryat district; Trans-Baikal Territory: Aginsky Buryat District

in Mongolia Cyrillic (Mongolian alphabet)

in the People's Republic of China, Old Mongolian writing

Mongolian(self-name: mongɣol xele, Mongol Hal listen)) is the language of the Mongols, the official language of Mongolia. The term can be used more widely: for the Mongolian language of Mongolia and Inner Mongolia in China, for all languages of the Mongolian group, in a historical context for languages such as ancient Common Mongolian and Old Written Mongolian languages.

Mongolian language in the narrow sense

The language of the Mongols is the main population of Mongolia, as well as Inner Mongolia and the Russian Federation. Often called after the main dialect Khalkha-Mongolian or simply Khalkha.

Mongolian language group

Khalkha Mongolian, together with the Mongolian written language, is part of the Mongolian family of languages. This family is divided into the following groups:

- Northern Mongolian languages: Buryat, Kalmyk, Ordos, Khamnigan, Oirat;

- Southern Mongolian languages: Dagur, Shira-Yugur, Dongxiang, Bao'an, Tu (Mongolian);

- Mughal stands apart in Afghanistan.

By their structure, these are agglutinative languages with elements of inflection. The majority (except Kalmyk and Buryat) are characterized by impersonal conjugation. In the field of morphology, they are characterized, in addition, by the absence of a sharp line between inflection and word formation: for example, different case forms of the same word often function lexically as new words and allow a secondary declension, the basis of which is not the primary stem, but the case form . The role of possessive pronouns is played by special suffixes: personal and impersonal. The presence of predicative suffixes gives the impression that names can be conjugated. Parts of speech are poorly differentiated. The following parts of speech are distinguished: name, verb and immutable particles. Noun and adjective in most living and written languages are not differentiated morphologically and differ only in terms of syntax.

In the area of syntax, the characteristic position of the definition before the defined, the predicate is usually at the end of sentences and the lack of agreement in the case of the definition and the defined, as well as different members of the sentence.

The differences between the language of the Mongols of the MR and the language of the Mongols of Inner Mongolia affect phonetics, as well as such morphological parameters, which are very variable within the Mongolian family, such as the set of participial forms and the presence/absence of some peripheral case forms. The same type of differences exist between dialects within both the Mongolian language of the MR and within the language of the Mongols of Inner Mongolia. In reality, it is one language divided by a state border, with many dialects represented on both sides. The umbrella term modern Mongolian refers to this; In total, over 5 million (according to other estimates - up to 6 million) people speak it, that is, more than 3/4 of the entire Mongol-speaking population. About 6 thousand Mongolians live in Taiwan; 3 thousand, according to the 1989 census, lived in the USSR. The division has consequences mainly of an external linguistic nature: in the Republic of Moldova and in Inner Mongolia, literary norms are different (in the latter case, the norm is based on the Chahar dialect); In addition, the dialects of Inner Mongolia have experienced significant influence from the Chinese language (in the areas of vocabulary and intonation).

Historical Mongolian languages

With an even broader interpretation, the concept of “Mongolian language” expands not only geographically, but also historically, and then it includes the common Mongolian language, which existed until about the 12th century, as well as the old written Mongolian language - the common literary language of all Mongolian tribes from the 13th to the 17th century century The dialectal basis of the latter is unclear; in fact, it has always been a supra-dialectal form of purely written communication, which was facilitated by the writing (basically Uyghur) that did not convey the phonetic appearance of words very accurately, leveling out inter-dialectal differences. Perhaps this language was formed by one of the Mongol tribes that were destroyed or completely assimilated during the rise of Genghis Khan’s empire (presumably the Naimans, Kereits or Khitans). It is generally accepted that Old Written Mongolian reflects a more ancient stage in the development of Mongolian languages than any of the known Mongolian dialects; this explains its role in the comparative historical study of Mongolian languages.

In the history of written language, ancient (XIII-XV centuries), pre-classical (XV-XVII centuries) and classical (XVII - early XX centuries) stages are distinguished. The frequently used terms “Old Mongolian language” and “Middle Mongolian language” are used to designate the common, although dialectally fragmented, language of the Mongolian tribes before the 13th century and in the 13th-15th centuries. respectively.

Since the 17th century, in connection with the creation by Zaya-Pandita of the so-called clear script (todo-bichig), adapted to the peculiarities of the Oirat dialects, and the formation of the Oirat literary language, the classical old-written Mongolian language began to be used mainly in the eastern part of the Mongolian area - in Khalkha (outer Mongolia) and Inner Mongolia; The Buryats in the Russian Empire gradually developed a special Buryat version of the old written Mongolian language.

In Inner Mongolia, the old written language is still used today. In Buryatia, writing was introduced first on a Latin basis (in 1931), and then on a Cyrillic basis (in 1939); in the Mongolian People's Republic the Cyrillic alphabet was introduced in 1945; New literary languages developed there. In post-communist Mongolia, and partly in Buryatia, interest in the old written language is being revived; Its teaching is actively carried out.

The language of the monuments of the so-called “square script” of the 13th-14th centuries. due to the presence of a number of structural features, it is sometimes considered as a special variety of the widely understood Mongolian language.

Mongolian language and Cyrillic alphabet

There are 35 letters in the Mongolian alphabet:

| Pos. | Cyrillic | Name | IPA | ISO 9 | Standard Romanization |

THL | Library Congress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ahh | A | a | a | a | a | |

| 2 | BB | bae | p, pʲ, b | b | b | b | b |

| 3 | Vv | ve | w, wʲ | v | v | w | v |

| 4 | G | ge | ɡ, ɡʲ, k, ɢ | g | g | g | g |

| 5 | Dd | de | t, tʲ, d | d | d | d | d |

| 6 | Her | e | jɛ~jɜ, e | e | ye, ye | ye, yo | e |

| 7 | Her | e | jɔ | ë | yo, yo | yo | ë |

| 8 | LJ | zhe | tʃ, dʒ | ž | j | j | zh |

| 9 | Zz | ze | ts, dz | z | z | z | z |

| 10 | Ii | And | i | i | i | i | |

| 11 | Yikes | Khagas and | j | ĭ | i | ĭ | |

| 12 | (Kk) | ka | (kʰ, kʰʲ) | k | k | k | k |

| 13 | Ll | el | , ɮʲ | l | l | l | l |

| 14 | Mm | Em | , mʲ | m | m | m | m |

| 15 | Nn | en | , nʲ, | n | n | n | n |

| 16 | Ooh | O | o | o | o | o | |

| 17 | Өө | ө | ô | ö | ö | ö | |

| 18 | (PP) | pe | (pʰ, pʰʲ) | p | p | p | p |

| 19 | RR | er | , rʲ | r | r | r | r |

| 20 | Ss | es | s | s | s | s | |

| 21 | Tt | te | tʰ, tʰʲ | t | t | t | t |

| 22 | Ooh | at | u | u | u | u | |

| 23 | Үү | ү | ù | ü | ü | ü | |

| 24 | (FF) | fe, F, ef | () | f | f | f | f |

| 25 | Xx | heh, Ha | , xʲ | h | x | kh | kh |

| 26 | Tsts | tse | tsʰ | c | c | ts | ts |

| 27 | Hh | che | tʃʰ | č | č | ch | ch |

| 28 | Shh | sha, esh | š | š | sh | sh | |

| 29 | (Shch) | now, eshche | (stʃ) | ŝ | šč | shch | shch |

| 30 | Kommersant | hatuugiin temdeg | ʺ | ı | ʺ | ı | |

| 31 | Yyy | er ugiyn y | y | y | î | y | |

| 32 | bb | golden temdeg | ʹ | ʹ | ĭ | i | |

| 33 | Uh | uh | è | e | e | ê | |

| 34 | Yuyu | Yu | jʊ, | û | yu, yu | yu, yu | iu |

| 35 | Yaya | I | , | â | ya | ya | ia |

see also

Notes

Literature

- Large academic Mongolian-Russian dictionary, in 4 volumes. Edited by: A. Luvsandendev, Ts. Tsedendamb, G. Pyurbeev. Publisher: Academia, 2001-2004. ISBN 5-87444-047-X, 5-87444-141-7, 5-87444-143-3

- B. Sumyaabaatar(Mongolian), “Mongol khelniy oiroltsoo ugiin tovch tol” / “Concise Dictionary of the Mongolian Language,” 1966, 191 p.

- B. Sumyaabaatar (Mongolian), “Mongol khel, utgazohiol, aman zohiolyn nomzuy,” Bibliography of the Mongolian language, literature and oral folk art, 1972, 364 p.

- (Mong.) Amarzargal, B. 1988. BNMAU dah" mongol helnij nutgijn ajalguuny tol" bichig: halh ajalguu. Ulaanbaatar: ŠUA.

- Apatóczky, Ákos Bertalan. 2005. On the problem of the subject markers of the Mongolian language. In Wú Xīnyīng, Chen Gānglóng (eds.), Miànxiàng xīn shìjìde ménggǔxué. Běijīng: Mínzú Chūbǎnshè. 334-343. ISBN 7-105-07208-3.

- (Japanese) Ashimura, Takashi. 2002. Mongorugo jarōto gengo no -lɛː no yōhō ni tsuite. TULIP, 21: 147-200.

- (Mongolian) Bajansan, Ž. and Š. Odontör. 1995. Hel šinžlelijn ner tom joony züjlčilsen tajlbar tol . Ulaanbaatar.

- (Mongolian) Bayančoγtu. 2002. Qorčin aman ayalγun-u sudulul. Kökeqota: ÖMYSKQ. ISBN 7-81074-391-0.

- (Mong.) Bjambasan, P. 2001. Mongol helnij ügüjsgeh har’caa ilerhijleh hereglüürüüd. Mongol hel, sojolijn surguul: Erdem šinžilgeenij bičig, 18: 9-20.

- Bosson, James E. 1964. Modern Mongolian; a primer and reader. Uralic and Altaic series; 38. Bloomington: Indiana University.

- Brosig, Benjamin. 2009. Depictives and resultatives in Modern Khalkh Mongolian. Hokkaidō gengo bunka kenkyū, 7: 71-101.

- Chuluu, Ujiyediin. 1998. Studies on Mongolian verb morphology. Dissertation, University of Toronto.

- (Mong.) Činggeltei. 1999. Odu üj-e-jin mongγul kelen-ü ǰüi. Kökeqota: ÖMAKQ. ISBN 7-204-04593-9.

- (Mong.) Coloo, Ž. 1988. BNMAU dah" mongol helnij nutgijn ajalguuny tol" bichig: ojrd ajalguu. Ulaanbaatar: ŠUA.

- (English) Djahukyan, Gevork. (1991). Armenian Lexicography. In Franz Josef Hausmann (Ed.), An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography(pp. 2367–2371). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- (Chinese) Dàobù. 1983. Menggǔyǔ jiǎnzhì. Běijīng: Mínzú.

- (Mongolian) Garudi. 2002. Dumdadu üy-e-yin mongγul kelen-ü bütüče-yin kelberi-yin sudulul. Kökeqota: ÖMAKQ.

- Georg, Stefan, Peter A. Michalove, Alexis Manaster Ramer, Paul J. Sidwell. 1999. Telling general linguists about Altaic. Journal of Linguistics, 35: 65-98.

- Guntsetseg, D. 2008. Differential Object Marking in Mongolian. Working Papers of the SFB 732 Incremental Specification in Context, 1: 53-69.

- Hammar, Lucia B. 1983. Syntactic and pragmatic options in Mongolian - a study of bol and n". Ph.D. Thesis. Bloomington: Indiana University.

- Harnud, Huhe. 2003. A Basic Study of Mongolian Prosody. Helsinki: Publications of the Department of Phonetics, University of Helsinki. Series A; 45. Dissertation. ISBN 952-10-1347-8.

- (Japanese) Hashimoto, Kunihiko. 1993.<-san>no irony. MKDKH, 43: 49-94. Sapporo: Dō daigaku.

- (Japanese) Hashimoto, Kunihiko. 2004. Mongorugo no kopyura kōbun no imi no ruikei. Muroran kōdai kiyō, 54: 91-100.

- Janhunen, Juha (ed.). The Mongolic languages. - London: Routledge, 2003. - ISBN 0-7007-1133-3

- Janhunen, Juha. 2003a. Written Mongol. In Janhunen 2003: 30-56.

- Janhunen, Juha. 2003b. Para-Mongolic. In Janhunen 2003: 391-402.

- Janhunen, Juha. 2003c. Proto-Mongolic. In Janhunen 2003: 1-29.

- Janhunen, Juha. 2003d. Mongolian dialects. In Janhunen 2003: 177-191.

- Janhunen, Juha. 2006. Mongolic languages. In K. Brown (ed.), The encyclopedia of language & linguistics. Amsterdam: Elsevier: 231-234.

- Johanson, Lars. 1995. On Turkic Converb Clauses. In Martin Haspelmath and Ekkehard König (eds.), Converbs in cross-linguistic perspective. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter: 313-347. ISBN 978-3-11-014357-7.

- (Korean) Kang, Sin Hyen. 2000. Tay.mong.kol.e chem.sa č-uy uy.mi.wa ki.nung. Monggolhak, 10: 1-23. Seoul: Hanʼguk Monggol Hakhoe.

- Karlsson, Anastasia Mukhanova. 2005. Rhythm and intonation in Halh Mongolian. Ph.D. Thesis. Lund: Lund University. Series: Travaux de l’Institut de Linguistique de Lund; 46. Lund: Lund University. ISBN 91-974116-9-8.

- Ko, Seongyeon. 2011. Vowel Contrast and Vowel Harmony Shift in the Mongolic Languages. Language Research, 47.1: 23-43.

- (Mongolian) Luvsanvandan, Š. 1959. Mongol hel ajalguuny učir. Studio Mongolica , 1.

- (Mongolian) Luvsanvandan, Š. (ed.). 1987. (Authors: P. Bjambasan, C. Önörbajan, B. Pürev-Očir, Ž. Sanžaa, C. Žančivdorž) Orčin cagijn mongol helnij ügzüjn bajguulalt. Ulaanbaatar: Ardyn bolovsrolyn jaamny surah bičig, setgüülijn negdsen rjedakcijn gazar.

- (Japanese) Matsuoka, Yūta. 2007. Gendai mongorugo no asupekuto to dōshi no genkaisei. KULIP, 28: 39-68.

- (Japanese) Mizuno, Masanori. 1995. Gendai mongorugo no jūzokusetsushugo ni okeru kakusentaku. TULIP, 14: 667-680.

- (Mongolian) Mönh-Amgalan, J. 1998. Orčin tsagijn mongol helnij bajmžijn aj. Ulaanbaatar: Moncame. ISBN 99929-951-2-2.

- Poppe, Nicholas. 1970. Mongolian language handbook. Washington D.C.: Center for Applied Linguistics.

- (Mongolian) Pürev-Očir, B. 1997. Orčin cagijn mongol helnij ögüülberzüj. Ulaanbaatar: n.a.

- Rachewiltz, Igor de. 1976. Some Remarks on the Stele of Yisuüngge. In Walter Heissig et al., Tractata Altaica - Denis Sinor, sexagenario optime de rebus altaicis merito dedicata. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 487–508.

- Rachewiltz, Igor de. 1999. Some reflections on the so-called Written Mongolian. In: Helmut Eimer, Michael Hahn, Maria Schetelich, Peter Wyzlic (eds.). Studia Tibetica et Mongolica - Festschrift Manfred Taube. Swisttal-Odendorf: Indica et Tibetica Verlag: 235-246.

- (Mongolian) Rinchen, Byambyn (ed.). 1979. Mongol ard ulsyn ugsaatny sudlal helnij šinžlelijn atlas. Ulaanbaatar: ŠUA.

- Rybatzki, Volker. 2003. Middle Mongol. In Janhunen 2003: 47-82.

- (Mongolian) Sajto, Kosüke. 1999. Orčin čagyn mongol helnij "neršsen" temdeg nerijn onclog (temdeglel). Mongol ulsyn ih surguulijn Mongol sudlalyn surguul" Erdem šinžilgeenij bičig XV bot", 13: 95-111.

- (Mong.) Sanžaa, Ž. and D. Tujaa. 2001. Darhad ajalguuny urt egšgijg avialbaryn tövšind sudalsan n". Mongol hel šinžlel, 4: 33-50.

- (Russian) Sanzeev, G. D. 1953. Sravnitel’naja grammatika mongol’skih jazykov. Moscow: Akademija Nauk USSR.

- (Mong.) Sečen. 2004. Odu üy-e-yin mongγul bičig-ün kelen-ü üge bütügekü daγaburi-yin sudulul. Kökeqota: ÖMASKKQ. ISBN 7-5311-4963-X.

- Sechenbaatar, Borjigin. 2003. The Chakhar dialect of Mongol: a morphological description. Helsinki: Finno-Ugrian society. ISBN 952-5150-68-2.

- (Mong.) Sečenbaγatur, Qasgerel, Tuyaγ-a [Tuyaa], Bu. Jirannige, Wu Yingzhe, Činggeltei. 2005. . New Haven: American Oriental Society. American Oriental series; 42.

- Street, John C. 2008. Middle Mongolian Past-tense -BA in the Secret History. Journal of the American Oriental Society 128 (3): 399-422.

- Svantesson, Jan-Olof. 2003. Khalkha. In Janhunen 2003: 154-176.

- Svantesson, Jan-Olof, Anna Tsendina, Anastasia Karlsson, Vivan Franzén. 2005. The Phonology of Mongolian. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926017-6.

- (Mongolian) Temürcereng, J̌. 2004. Mongγul kelen-ü üge-yin sang-un sudulul. Kökeqota: ÖMASKKQ. ISBN 7-5311-5893-0.

- (Mong.) Toγtambayar, L. 2006. Mongγul kelen-ü kele ǰüiǰigsen yabuča-yin tuqai sudulul. Liyuuning-un ündüsüten-ü keblel-ün qoriy-a. ISBN 7-80722-206-9.

- (Mongolian) Tömörtogoo, D. 1992. Mongol helnij tüühen helzüj. Ulaanbaatar.

- (Mongolian) Tömörtogoo, D. 2002. Mongol dörvölžin üsegijn durashalyn sudalgaa. Ulaanbaatar: IAMS. ISBN 99929-56-24-0.

- (Mongolian) Tsedendamba, Ts., Sürengijn Möömöö (eds.). 1997. Orčin cagijn mongol hel. Ulaanbaatar.

- Tserenpil, D. and R. Kullmann. 2005. Mongolian grammar. Ulaanbaatar: Admon. ISBN 99929-0-445-3.

- (Mongolian) Tümenčečeg. 1990. Dumdadu ǰaγun-u mongγul kelen-ü toγačin ögülekü tölüb-ün kelberi-nügüd ba tegün-ü ularil kögǰil. Öbür mongγul-un yeke surγaγuli, 3: 102-120.

- The end of the Altaic controversy (review of Starostin et al. 2003)

- Walker, Rachel. 1997. Mongolian stress, licensing, and factorial typology. Rutgers Optimality Archive, ROA-172.

- (German) Weiers, Michael. 1969. Untersuchungen zu einer historischen Grammatik des präklassischen Schriftmongolisch. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. Asiatische Forschungen, 28. (Revision of 1966 dissertation submitted to the Universität Bonn.)

- Yu, Wonsoo. 1991. A study of Mongolian negation. Ph. D. Thesis. Bloomington: Indiana University.

Links

- Monumenta Altaica - Altai linguistics - grammars, texts, dictionaries; everything about Mongolian languages and peoples.