Henry Ford's book “My Life, My Achievements” went through more than a hundred editions in more than half the countries of the world. In fact, this is the autobiography of a world-famous person who organized a continuous conveyor automobile production, written in bright and figurative language with great energy and inspiration.

The book presents not only unique material, interesting from a historical point of view, but also relevant for practice and sociologists, designers and engineers, economists and managers even today, almost a century later, because is a classic work on the scientific organization of labor activity. But, of course, the work “My Life, My Achievements” will also be of interest to a wide range of readers, as a motivating, inspiring and endlessly informative book.

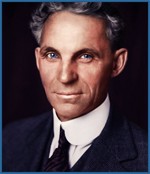

About Henry Ford

Henry Ford is a famous American industrialist and inventor, organizer and owner of automobile factories, author of more than 160 patents. This man is also known for being the first to put car production on an industrial assembly line. The conveyor had been used in production before, but it was Ford who began to use it for car production. The result of Ford's activities was the sale of millions of Ford cars, and the industrialist himself became the head of the very successful Ford Motor Company corporation, which still exists today (you can read about Henry Ford and other outstanding leaders).

Henry Ford is a famous American industrialist and inventor, organizer and owner of automobile factories, author of more than 160 patents. This man is also known for being the first to put car production on an industrial assembly line. The conveyor had been used in production before, but it was Ford who began to use it for car production. The result of Ford's activities was the sale of millions of Ford cars, and the industrialist himself became the head of the very successful Ford Motor Company corporation, which still exists today (you can read about Henry Ford and other outstanding leaders).

Summary of the book “My Life, My Achievements”

The book consists of a preface, an introduction, seventeen chapters and an afterword. Guided by the fact that there are a lot of interesting ideas in the book, and, in fact, there are quite a few chapters, we decided to highlight the most interesting, in our opinion, thoughts of Henry Ford on certain topics.

About the changes

There is no need to fear the future or revere the past. Otherwise, the person himself narrows the scope of his capabilities. are a reason for a new beginning and smarter actions. It is shameful not to fail, but to be afraid to fail. The past can only be useful by pointing to new paths of development.

It doesn't come down to fighting. If you need to fight, then only with your own inertia and. If we want to grow, we must wake up and be awake. Life is a journey, and those who rest do not stand still, but roll downhill. In fact, everything is always in a state of flux.

Regarding profit

Work should, first of all, be for the common good, but you shouldn’t forget about profit. A good enterprise should bring both profit and benefit. However, profit should be a result, not a goal.

If money is at the forefront, work slows down, and... An obsession with money creates a fear of failure, which excludes the right business approach, makes you fear competitors and everything that can affect the conduct of business.

The only source of profit for an organization is production, but this does not mean that a businessman should not understand financial issues. It’s just better to understand less about finance, so that you don’t have the desire to engage in financial transactions instead of being a real producer. It is important to understand that there is nothing wrong with loans or bankers. There is something bad about trying to replace work with credit.

Loans do not allow you to see the real side of financial affairs, and also contribute to the development of laziness. Many entrepreneurs are too lazy to dig out the cause of losses, or too proud to accept the fact that they failed in some way.

Production should not be understood as buying cheap and selling dearly. Manufacturing is about purchasing raw materials at the right price and turning them into a top quality product. If a businessman engages in speculative activities, participates in the race for money and plays dishonestly, he slows down production.

About prices

Even if the company is not doing very well, you can always find a consumer - you just need to keep the prices low enough. Inflated prices are a sign of unhealthy businesses and abnormal economies. If , then he will have a normal temperature; if the market is healthy, it will have normal prices.

Outdated views say that prices should be raised as long as the consumer can pay. But the new business vision suggests the opposite. If lawyers or bankers with old views are introduced into business, nothing good will come of it.

By lowering prices, you can achieve an increase in turnover and even business expansion. Once the profit from the production of Ford cars was so high that it was decided to return $50 to each customer.

Henry Ford's life goal was to ensure that as many people as possible could buy cars, and that as many workers as possible would have stable, well-paid jobs. And Henry Ford was sure that if he had not insisted on moderate incomes for himself and his partners, he would have failed completely.

Regarding management

When large numbers of people work together, the greatest evil they have to contend with is overmanagement. The most dangerous beast is a brilliant manager who loves to draw up diagrams with functions, positions, names.

An enterprise is not a machine. It is a community designed to work, not exchange information. And what is happening in one workshop does not necessarily need to be known to another workshop. If a person is seriously busy with his own work, he will not be interested in someone else's.

The manager's task is to ensure that all links. But for the work to be effective, it is not at all necessary to love each other. And excessive camaraderie can cause failure when one covers for the other, and this is harmful for both.

Henry Ford's company was never distinguished by a complex administrative apparatus, and achieved its fame thanks to its products, and not to the gigantic buildings in which these products were manufactured.

Regarding wages

Typically, the manager or owner of an enterprise does not call his employees partners, but that is exactly what they are. Every entrepreneur who cannot cope with the task on his own attracts partners to the activity. Why doesn’t a manufacturer who can’t cope with production with his own hands call those whom he called to help his enterprise partners? Absolutely any business that requires more than one person to manage it implies a partnership. And at the moment when an entrepreneur attracts a person to help, even if it is a messenger, he already attracts a partner.

An employer who considers himself an ambitious person must pay his employees higher wages than his competitors pay theirs. Employees must help the employer realize these ambitious intentions.

Many of Henry Ford's competitors were convinced that wages were high because of good business or the need for advertising. They condemned the management of the Ford Motor Company for abandoning the tradition of paying workers what they were willing to take.

But poverty cannot be overcome this way, and reform in this area was carried out by Ford for the reason that it was necessary to strengthen the foundation of the company. Henry Ford said that they were not just giving money away, but thinking about the future, because a company that pays its employees little will never be sustainable. And a world in which everyone has everything they need is the best world.

Finally

Naturally, Henry Ford in his book “My Life, My Achievements” discusses other interesting topics: where does any business and production begin, what can be learned from these processes, what is the relationship between people and machines, money and goods, why it is important to do good deeds and how to produce goods inexpensively, what is the point of poverty and what is good in charity, etc.

Henry Ford was a phenomenon who managed to revolutionize not only the automobile industry, but also the minds of people. Millions listened to his ideas during his lifetime and continue to listen to them now. And, speaking frankly, reading “My Life, My Achievements” is recommended for everyone who is interested in achieving success and, of course, business and economics.

A book written in 1924 that changed ideas about doing business and the relationship between employer and subordinates. This is an autobiographical summary of Henry Ford's most important principles, the effectiveness of which is confirmed by the success of his automobile empire. A book that inspires and inspires, gives answers to typical questions of a newbie in the business environment and forces you to radically change your worldview in order to achieve success.

Strictly speaking, Henry Ford's book "My Life, My Achievements" can hardly be called an autobiography in the classical sense of the word. This work is more reminiscent of modern business textbooks, concepts and strategies in the style of Arkhangelsky, Kiyosaki, etc., rather than a detailed biography. And this is not surprising, because the entire life of the founder of the largest automobile empire was inextricably linked with his favorite business. What Steve Jobs would later describe in his famous speech to Stanford University graduates as “the great luck of finding your path at an early age.”

The truly great inventor and businessman Henry Ford worked actively on the problem of employee motivation. While the mentioned Jobs was so able to generate and develop the spirit of competition and infect with a new idea that his employees happily fought not for an increase in salaries, but for T-shirts with the inscriptions “I worked 24/36/72 hours without a break,” etc. . For Ford, motivation played a special role. Material support for employees allowed them to buy cars made with their own hands. And this was one of the main principles of the entrepreneur - everyone should be able to purchase a high-quality and comfortable car for city life.

The book itself has a small volume of about 125-140 pages, depending on the year of publication and version. Earlier versions did not include two chapters, so they were 12-15 pages shorter, and only in 2011 in Russia the book was published in its full version.

The language of the narrative is simple and understandable, designed for a wide range of readers and allows representatives of various professions and fields of activity to understand the basic ideas and methods. Towards the end, the conceptual-categorical apparatus becomes somewhat more complicated, but the reader is already up to speed and is gradually learning to understand the ideas of the great Ford.

Most critics and readers agree that the absence of excessive lyrics and fluff in the narrative makes an autobiography an excellent tool for self-development and a ready-made guide to action. But this feature is not accidental, because Henry Ford himself does not like to waste time, money and effort in vain.

He was the one who came up with the idea eight hour working day and a six- and then a five-day working week. At the same time, providing his workers with everything they needed, not pushing them, but supporting them, he was categorically against trade unions. This position is completely justified and logical, given his attitude towards the workers themselves. It seems that when creating the most comfortable workplace for productive activity and fairly high wages, it would be inappropriate to demand the protection of any other rights and interests of workers.

Researchers separately note the fact that Ford himself had an extremely negative attitude towards Jews and during World War II actively collaborated with the Germans, thanks to which his factories in the occupied lands were not destroyed, but continued to operate. A portrait of the great innovator hung in the office of Adolf Hitler, who considered him his inspiration. The use of some of Ford's early works for anti-Semitic propaganda by the NSDAP and later by the Wehrmacht somewhat tarnished the American businessman's reputation. After several high-ranking officials, politicians, cultural figures and the US President himself condemned him in a public letter, Ford wrote that he renounced his views regarding Jews, asked for their forgiveness and promised not to publish any works on this topic in the future.

One can assess the personality of Henry Ford differently, taking into account one or another aspect of his activity, but it is impossible not to admit that this man largely predetermined the course of development of the era.

A 100% workaholic, he strongly supported the creative initiatives of his employees, inspired them by his own example, encouraged and tried to give impetus to the development of each of them. Later, his desire to control everything even resulted in total surveillance of key factory workers, but after some time he recognized this method as a failure and agreed to give them more freedom.

The book will give you answers to the following questions:

- how to dramatically change your own life;

- is it possible to free oneself from the oppression of conditions imposed by the environment and superiors;

- is it possible to create your own business from scratch and achieve success without connections and start-up capital;

- how to properly manage money and increase it;

- what is the meaning of any creative or business activity;

- how to combine personal enrichment with the idea of creating equal and free conditions for earning money and achieving a high social status for your subordinates.

Overall, the book leaves you with pleasant emotions and inspiration after reading it. She can become a powerful motivator for those who want to achieve something. Definitely recommended reading for any age.

Henry Ford

My life, my achievements

Preface

This book has traveled to almost all states. It is printed in many languages. Her publications sold in great demand everywhere.

The burning interest in it was created not by artificial advertising hype, but by its very content: - behind this book is the life and work of a very great person, behind it is the practical experience of the creator of a production unprecedented in scale and organization.

Much has been written about him as a billionaire, as the greatest industrialist of the New World, as a brilliant ignorant mechanic. But he himself remained silent, not speaking either in literature or in the press.

And now, finally, Ford's book about himself has appeared. She immediately became famous.

The entire life of Ford, this sixty-year-old, the richest man in the world, is full of outstanding moments. Particularly interesting is the beginning of his career, when he, heroically overcoming material obstacles and not getting enough sleep at night, spent two and a half years developing his own, still unsurpassed, car model.

Now he is a billionaire industrialist, engineer, businessman, candidate for President of the United States, of course, looking for explanations, if not justifications, for his activities before the revolution in this book and for himself.

The figure of this man cannot surprise with his rigidity of thought; on the contrary, it would be strange to see the opposite in him under all conditions.

The clashes that Ford had with himself did not pass unnoticed for him, and he found easy explanations for them: all people are different, there can be no equality, even two Fords are not equal to each other, the author notes, not seeing in his recognition to himself the same sentence.

This colossus, it seems, has risen in our time only to bring it down at the pinnacle of capitalism. Ford's opposition to future forms of life is inexpressibly strong. A pacifist at the beginning of the World War, who was even sued over peacekeeping activities, and then a conscious militarist, who provided enormous assistance during the period of America’s participation in the war - all the time, Ford, continuing to sail along the course of capitalist profit, did not leave the imperialist boat.

Ford is completely original and is not like other American billionaires: Carnegie, Rockefeller, Morgan, etc., who glorify the usefulness of capital for society, but he does not go far from them, converging with them in a single goal. The foreign press writes wonders about Ford as an industrialist, and recommends following his ideas and examples of his production, especially for Germany, forgetting that there are no or almost no imitators of him in terms of the scientific organization of production, even in America itself, where there were only unsuccessful followers.

There would be no place to explain the reason for the latter: it apparently lies in the talent of the system invented by Ford, which, like any perfect system, alone guarantees better organization. However, from here there is still a long way to go to organize the country’s national economy, which Ford talks about every now and then.

In his book, Ford writes what he learned in production, but this proves that, having learned and created, he did not understand production itself. He did not understand the economic essence of the production process, although he perfectly establishes it in practice. That is why he does not understand Fordism, which he rebels against. Ford is against socialism and Fordism with all his being.

Ford is against wage equality and does not understand the essence of his achievements - the force of inertia that develops in the process. On the contrary, he is only for an increase in pay, thereby wanting to ingrain in the workers a feeling of dependence on the enterprise, which is why he calls his workers his companions. And despite the fact that the entire system formed by the skillful organization of the production process is aimed at the destruction of craftsmanship and privileged specialists who are not needed for the mass production of things when dividing labor into operations, Ford does not see or appreciate any special utility in this.

Had Ford loosened his thinking, freed himself from the hereditary shackles of the century, he would have done even more for Fordism. But while enriching himself, he allocates only a small share and, moreover, only for his workers.

Fordism is a system whose principles have long been known, laid down by Marx and constitute the law of the division of labor. A manufacturing model is only beneficial for production when it can be easily split into operations, the number of which should be neither large nor small. The process, done correctly, is marked by the rhythmic action of making, where fast work can be just as unprofitable as slow work. The unnoticed natural force of inertia or the production boom that develops in the process constitutes the element of Fordism.

The conveyors created by Ford on this basis for progressive assembly, the procurement of things in mass quantities, the cycle of rotation of materials and the production of processed manufactured goods as a whole also constitute Fordism, which is ensured by an internal system that destroys all qualifications and specialization and therefore requires equalization of wages.

The precision of manufacturing, which is due to the depersonalization of labor, reaches Ford up to one ten-thousandth of an inch.

The speed of production and the developed inertia introduced into the process of collective labor gives a mass result in the production of things.

Refusing to see in good cars the meaning that is incorrectly attributed to them, like any technology, Ford guesses a perfect organization of production, consisting of many elements of Fordism, but not just one. A perfect organization does not consist of good machines and good people, but consists of what we generally call a system.

– Less schemes, bureaucracy, titles, posts, veneration, patronage! - Ford proclaims, dreaming of correcting capitalist production, which lacks the perfection of the system. Ford constantly confuses the organization of business and individual production with the economy of the country.

Ford goes against the definitions of financial science and is at war with credit and banks, while at the same time being also a kind of banker himself.

He is not a supporter, as he says, of capital, which can do everything, and not a supporter of the production of profit, considering himself free from the violence of capital.

For all Russian citizens, it is not Ford’s inventions that are edifying, but the fundamentals of his economy and production. The interest of his book lies mainly in the practice of both production and large financial transactions. The success of all this gave Ford the idea of the possibility of a close partnership between owner and employee.

There are several turning points in Ford's industrial journey that appear intertwined to be technical and economic.

Before the progressive assembly of automobiles invented by Ford, never before had a mass of individual items been sent from the factory to places of sale without the risk of not being assembled there, but when this mass at the Ford plant flowed like lava, produced by emigrants of 53 nationalities, Ford found itself in the need to ensure its export and transportation of materials via new railway lines.

This new turning point led to the need to adapt transportation to production, and Ford purchases an entire railroad line from the government.

At this point, vehicle assembly at the plant ceases and is transferred to 30 locations in America. “Cost” changes; Most of the overhead costs are allocated to warehouses, sales and assembly points. Trade processes merged with production processes, dispersing part of the total costs. Imperceptibly, production, consumption and distribution are regrouped, affecting selling prices.

Ford has long predicted that for his business he will not be afraid of duties and tariffs, since the procurement mass of automobile parts disperses overhead costs, withstanding very long distances to deliver them to the site, with relatively short distances from where the materials for them are received at the plant .

The significance acquired by mass production, which destroyed distance and significantly reduced the applicability of credit to production, provided new ways for the formation of the accumulation of hitherto unprecedented amounts of capital, folded in one hand.

In short, Ford's production recreated an industry in which credit no longer played its usual role.

Henry Ford

My life, my achievements

Introduction

My guiding idea

Our country has just begun to develop; no matter what they say about our amazing successes, we barely plowed the top cover. Despite this, our successes were quite amazing. But if we compare what has been done with what remains to be done, all our successes turn into nothing. One has only to remember that more force is expended to plow the land than in all the industrial enterprises of the country combined, and one immediately gets an idea of the possibilities that lie before us. And precisely now, when so many states are experiencing a process of fermentation, now, with anxiety reigning everywhere, the moment has apparently come when it is appropriate to recall something from the area of the upcoming tasks, in the light of the problems that have already been resolved.

When one starts talking about the increasing power of machines and industry, we easily see an image of a cold, metallic world in which trees, flowers, birds, meadows are crowded out by the grandiose factories of a world consisting of iron machines and human machines. I do not share this idea. Moreover, I believe that unless we learn to use machines better, we will not have time to enjoy trees and birds, flowers and meadows.

In my opinion, we have done too much to frighten away the joy of life with the thought of the opposition between the concepts of “existence” and “earning a livelihood.” We waste so much time and energy that we have little left for the pleasures of life. Power and machinery, money and property are useful only insofar as they contribute to the freedom of life. They are only a means to an end. For example, I look at cars that bear my name as more than just cars. If only they were, I would have done something different. To me they are clear evidence of a business theory that I hope is more than a business theory, but a theory that aims to make the world a source of joy. The fact of the extraordinary success of the Ford Automobile Society is important in that it irrefutably demonstrates how correct my theory has hitherto been. Only with this premise can I judge existing methods of production, finance and society from the point of view of a person not enslaved by them.

If I pursued only selfish goals, there would be no need for me to strive to change established methods. If I thought only about acquisition, the present system would be excellent for me; she supplies me with money in abundance. But I remember the duty of service. The present system does not give the highest measure of productivity, because it encourages waste in all its forms; from many people it takes away the product of their labor. She has no plan. It all depends on the degree of planning and expediency.

I have nothing against the general tendency to ridicule new ideas. It is better to be skeptical of all new ideas and demand proof of their correctness than to chase every new idea in a state of continuous circulation of thoughts. Skepticism, coinciding with caution, is the compass of civilization. There is no idea that is good just because it is old, or bad because it is new; but, if the old idea has justified itself, then this is strong evidence in its favor. Ideas themselves are valuable, but every idea is, after all, just an idea. The challenge is to implement it practically.

First of all, I want to prove that the ideas we apply can be applied everywhere, that they concern not only the field of cars or tractors, but are, as it were, part of some general code. I am firmly convinced that this code is completely natural, and I would like to prove this with such immutability that would result in the recognition of our ideas not as new, but as a natural code.

It is quite natural to work in the consciousness that happiness and prosperity can only be achieved by honest work. Human misfortunes are largely the result of attempts to turn away from this natural path. I do not propose to propose anything that goes beyond the unconditional recognition of this natural principle. I start from the assumption that we have to work. The successes we have achieved so far are, in essence, the result of a certain logical comprehension: since we have to work, it is better to work smartly and prudently; The better we work, the better off we will be. This is what, in my opinion, elementary, common human sense prescribes to us.

One of the first rules of caution teaches us to be on our guard and not to confuse reactionary action with reasonable measures. We have just experienced a period of fireworks in every respect and have been inundated with programs and plans for idealistic progress. But we didn’t move on from this. All together it looked like a rally, but not a forward movement. I got to hear a lot of wonderful things; but, upon arriving home, we discovered that the fire in the hearth had gone out. Reactionaries usually take advantage of the depression that follows such periods and begin to refer to the “good old days” - mostly filled with the worst ancient abuses - and since they have neither foresight nor imagination, then on occasion they pass for “practical people” . Their return to power is often hailed as a return to common sense.

The main functions are agriculture, industry and transport. Without them, social life is impossible. They hold the world together. The cultivation of the land, the production and distribution of consumer goods are as primitive as human needs, and yet more vital than anything else. They contain the quintessence of physical life. If they die, then public life will cease.

Any amount of work. Things are nothing more than work. On the contrary, speculation in finished products has nothing to do with business - it means nothing more and nothing less than a more decent form of theft, which cannot be eradicated by legislation. In general, little can be achieved through legislation: it is never constructive. It is incapable of going beyond the limits of police power, and therefore it is a waste of time to expect from our government agencies in Washington or in the main cities of the states what they cannot do. As long as we expect legislation to cure poverty and eliminate privilege from the world, we are destined to see poverty increase and privilege increase. We have relied on Washington for too long and we have too many legislators - although they still do not have as much freedom here as in other countries - but they attribute to the laws a power that is not inherent to them.

If you inspire a country, such as ours, that Washington is heaven, where omnipotence and omniscience sit on thrones above the clouds, then the country begins to fall into dependence, which does not promise anything good in the future. Help will come not from Washington, but from ourselves; Moreover, we ourselves may be able to help Washington, as a kind of center where the fruits of our labors are concentrated for their further distribution for the common benefit. We can help the government, not the government us.

The motto: “less administrative spirit in business life and more business spirit in administration” is very good, not only because it is useful both in business and in government, but also because it is useful to the people. The United States was not created for business reasons. The Declaration of Independence is not a commercial document, and the Constitution of the United States is not a catalog of goods. The United States - country, government and economic life - are only the means to give value to the life of the people. The government is only his servant, and must always remain so. As soon as the people become an appendage to the government, the law of retaliation comes into force, for such a relationship is unnatural, immoral and inhumane. It is impossible to do without business life and without government. Both, playing a service role, are as necessary as water and bread; but, starting to rule, they go against the natural order. Taking care of the well-being of the country is the duty of each of us. Only under this condition will the matter be handled correctly and reliably. Promises cost the government nothing, but it is unable to implement them. True, governments can juggle currencies, as they did in Europe (and as financiers are still doing and will do all over the world as long as the net income ends up in their pocket); At the same time, there is a lot of solemn nonsense7 | And yet work and only work is able to create values. Deep down, everyone knows this.

It is highly improbable that such an intelligent people as ours would be able to suppress the basic processes of economic life. Most people feel instinctively - without even realizing it - that money is not wealth. Vulgar theories that promise everything to everyone and demand nothing are immediately rejected by the instinct of the average person, even when he is not able to logically comprehend such an attitude towards them. He knows they are lies, and that is enough. The current order, despite its clumsiness, frequent mistakes and various kinds of shortcomings, has the advantage over any other that it functions. Undoubtedly, the current order will gradually transform into another, and another order will also function - but not so much on its own, as depending on the content people put into it. Is our system correct? Of course it is wrong, in a thousand ways. Heavy? Yes! From the point of view of law and reason, it should have collapsed long ago. But she holds on.

The economic principle is labor. Labor is a human element that takes advantage of the fruitful seasons of the year. Human labor has made the harvest season what it is today. The economic principle states: Each of us works on material that was not created by us and which we cannot create, on material that is given to us by nature.

A moral principle is a person’s right to his work. This right finds various forms of expression. A man who has earned his bread has also earned the right to it. If another person steals this bread from him, he steals from him more than bread, he steals a sacred human right.

If we are unable to produce, we are unable to possess. Capitalists, made so by trading money, are a temporary, necessary evil. They may not even be evil if their money is put back into production. But if their money is used to impede distribution, to erect barriers between consumer and producer, then they are truly pests whose existence will cease as soon as money is better adapted to labor relations. And this will happen when everyone comes to the realization that only work, work alone, leads to the right path to health, wealth and happiness.

There is no reason why a person who wants to work should not be able to work and receive full compensation for his work. Equally, there is no reason why a person who is able to work, but does not want to, should not also receive full compensation for what he has done. In all circumstances he must be given the opportunity to receive from society what he himself has given to society. If he has given nothing to society, then he has nothing to demand from society. Let him be given the freedom to die of hunger. Arguing that everyone should have more than they actually deserve - just because some get more than their rightful share - will not get us very far.

There can be no statement more absurd and more harmful to humanity than that all men are equal.

In nature, no two objects are absolutely equal. We build our cars with nothing less than interchangeable parts. All these parts are similar to each other as only they can be similar when using chemical analysis, the most precise instruments and the most precise production. There is, therefore, no need for testing. When you see two Fords, so similar in appearance to each other that no one can tell them apart, and with parts so similar that they can be put one in the place of the other, it involuntarily occurs to you that they are, in fact, the same. But this is by no means true. They work differently. We have people who have driven hundreds, sometimes thousands of Ford cars, and they claim that no two cars are exactly alike; that if they drove a new car for an hour or less and this car was then placed in a row of other cars, which they also tested for an hour under the same conditions, although they would not be able to distinguish individual cars by appearance, they would still distinguish them in riding.

Hitherto I have spoken of various subjects in general; Let's now move on to specific examples. Each one should be placed so that the scale of his life is in due proportion to the services he renders to society. It is timely to say a few words on this subject, for we have just passed through a period when, with regard to most people, the question of the amount of their services was the last priority. We were on our way to reaching a point where no one asked for these services anymore. Checks arrived automatically. Previously, the customer honored the seller with his orders; Subsequently, the relationship changed and the seller began to honor the client by fulfilling his orders. In business life this is evil. Every monopoly and every pursuit of profit is evil. It is invariably harmful for the enterprise if there is no need to strain. An enterprise is never as healthy as when, like a chicken, it must find part of its food itself. Everything came too easily in business life. The principle of a definite, real correspondence between value and its equivalent has been shaken. There was no longer any need to think about satisfying the clientele. In certain circles, even a kind of tendency to drive the public to hell has prevailed. Some referred to this state as “the heyday of business life.” But this by no means meant prosperity. It was simply an unnecessary pursuit of money, which had nothing to do with business life.

If you don't always have a goal in mind, it's very easy to overload yourself with money and then, in your constant effort to make more money, completely forget about the need to provide the public with what they really want. Doing business on the basis of pure profit is an extremely risky enterprise. It is a kind of gambling that proceeds unevenly and rarely lasts longer than a few years. The task of an enterprise is to produce for consumption, and not for profit or speculation. And the condition for such production is that its products be of good quality and cheap, so that these products serve the benefit of the people, and not just one producer. If the issue of money is viewed from a false perspective, then the products are falsified to please the manufacturer.

The well-being of the producer ultimately also depends on the benefits he brings to the people. True, for some time he can conduct his affairs well, serving exclusively himself. But it won't last long. Once the people realize that the manufacturer is not serving them, the end is not far off. During the war boom, producers were primarily concerned with serving themselves. But as soon as the people saw this, many of them came to an end. These people claimed that they were in a period of “depression.” But that was not the case. They simply tried to use ignorance to fight common sense, and such a policy never succeeds. Greed for money is the surest way to not achieve money. But if you serve for the sake of service itself, for the satisfaction that comes from the consciousness of the rightness of the cause, then money will appear in abundance by itself.

Money, quite naturally, comes from useful activities. Having money is absolutely necessary. But we must not forget that the purpose of money is not idleness, but the multiplication of funds for useful service. For me personally, there is nothing more disgusting than an idle life. None of us have a right to it. There is no place for parasites in civilization. All kinds of projects for the destruction of money only lead to a complication of the issue, since it is impossible to do without exchange symbols. Of course, it remains in great doubt whether our present monetary system provides a sound basis for exchange. This is a question that I will touch upon more closely in a later chapter. My main objection to the current monetary system is that it is often treated as an end in itself. And under this condition, in many respects it retards production instead of promoting it.

My goal is simplicity. In general, people have so little, and the satisfaction of the basic needs of life (not to mention the luxuries to which, in my opinion, everyone has a certain right) costs so much, that almost everything we produce is much more complex than necessary. Our clothes, homes, apartment furnishings - everything could be much simpler and at the same time more beautiful. This is because all objects in the past were made in a certain way, and today's manufacturers follow the beaten path.

By this I do not want to say that we should go to the other extreme. There is absolutely no need for this. There is no need for our dress to consist of a bag with a hole for sticking the head through. True, in this case it would be easy to manufacture, but it would be extremely impractical. The blanket is not a masterpiece of tailoring, but none of us would get much done if we walked around, like the Indians, in blankets. True simplicity is associated with an understanding of the practical and expedient. The disadvantage of all radical reforms is that they want to change a person and adapt him to certain subjects. I believe that attempts to introduce "reform" dress for women invariably come from ugly people who want other women to be ugly. In other words, everything happens topsy-turvy. You should take something that has proven its usefulness and eliminate everything unnecessary in it. This primarily applies to shoes, clothing, houses, cars, railways, ships, and aircraft. By eliminating unnecessary parts and simplifying necessary ones, we simultaneously eliminate unnecessary production costs. The logic is simple. But, oddly enough, the process most often begins with reducing the cost of production, and not with simplifying the product. We must start from the fabric itself. It is important, first of all, to examine whether it is really as good as it should be - does it fulfill its purpose to the maximum extent? Then - was the material used the best possible or only the most expensive? And finally, does it allow for simplifications in design and weight reduction? And so on.

Excess weight is as meaningless in any object as the badge on a coachman's hat - perhaps even more meaningless. A badge may, after all, serve as a means of identification, while excess weight only means wasted strength. It’s a mystery to me what the mixture of gravity and force is based on. Everything is very good in a pile driver, but why put extra weight into motion when nothing is achieved? Why burden a machine intended for transport with special weight? Why not transfer the excess weight to the load being transported by the machine? Fat people cannot run as fast as thin people, and we make most of our transport vehicles so bulky, as if dead weight and bulk increase speed! Poverty largely comes from dragging dead weights.

In the matter of eliminating unnecessary heaviness, we will still make great progress, for example, in relation to wood materials. Wood is an excellent material for some parts, although very uneconomical. The wood that goes into a Ford car contains about 30 pounds of water. Undoubtedly, improvements are possible here. A means must be found by which the same power and elasticity will be achieved, without excess weight. The same is true for a thousand other items.

The farmer makes his day's work too difficult. In my opinion, the average farmer spends no more than five percent of his energy on really useful work. If a factory were set up on the model of an ordinary farm, it would need to be filled with workers. The worst factory in Europe is hardly organized as badly as an ordinary peasant farm. Mechanical energy and electricity are almost never used. Not only is everything done by hand, but in most cases no attention is even paid to expedient organization. During the course of a working day, a farmer probably climbs up and down a rickety ladder a dozen times. For years in a row he will be torn, carrying water, instead of laying a meter or two of water pipe. If there is a need for additional work, then his first thought is to hire additional workers. He considers it an unnecessary luxury to spend money on improvements. That is why agricultural products, even at the lowest prices, are still too expensive and the farmer’s income, under the most favorable conditions, is negligible. The predatory waste of time and effort is the reason for high prices and low earnings.

On my own farm in Dearborn, everything is done with machines. But although in many respects limits have been set on the waste of energy, we are still far from a truly economic economy. Until now, we have not yet had the opportunity to devote continuous attention to this issue for 5-10 years in order to establish what still requires implementation. More remains to be done than has been done. And yet we constantly received, regardless of market prices, excellent income. On our farm we are not farmers, but industrialists. As soon as the farmer learns to look upon himself as an industrialist, with all the latter's characteristic aversion to waste in material and labor, the prices of agricultural products will so fall and incomes will so rise that there will be enough for everyone to live on, and agriculture will acquire a reputation the least risky and most rewarding profession.

Insufficient familiarity with the processes and true essence of the profession, as well as with the best forms of its organization, lies the reason for the low profitability of farming. But everything that is organized on the model of agriculture is doomed to be unprofitable. The farmer hopes for happiness and his ancestors. He has no idea about economics of production and marketing. A manufacturer who knew nothing about economics of production and sales would not have lasted long. That the farmer is holding on is just proof of how amazingly profitable agriculture itself is. It is a supremely simple means to achieve cheap and significant production in both the industrial and agricultural fields - and production of this kind means that there is enough for everyone. But the worst thing is that there is a tendency everywhere to complicate even the simplest things. Here, for example, are the so-called “improvements”.

When it comes to improvements, a change in the product is usually designed. An “improved” product is one that has undergone a change. My understanding of the concept of “improvement” is completely different. I consider it generally wrong to start production until the product itself has been improved. This, of course, does not mean that changes should never be made to the fabrication. I only consider it more economical to undertake production experience only when there is complete confidence in the good quality and suitability of the calculations and materials. If such confidence is not obtained upon closer examination, then one should calmly continue research until confidence appears. Production must come from the product itself. The factory, organization, sales and financial considerations themselves adapt to the fabrication. In this way, the cutting edge of the enterprise is sharpened, and in the end it turns out that time is gained. Forcing a product without prior confidence in the product itself has been the hidden cause of many, many disasters. How many people seem to be sure that the most important thing is the structure of the factory, sales, financial resources, business management. The most important thing is the product itself, and any forcing of production before the product is perfected means a waste of effort. Twelve years passed before I completed the Model T, which satisfied me in every way, the one that now enjoys fame as a Ford car. We didn’t even make any attempts at first to start production in the proper sense until we got a real factory product. This latter has not undergone significant changes since then.

We are constantly experimenting with new ideas. Driving near Dearborn, you can come across all possible models of Ford cars. These are test vehicles, not new models. I don't ignore any good idea, but I shy away from immediately deciding whether it is actually good. If an idea turns out to be really good, or at least opens up new possibilities, then I am in favor of trying it in every possible way. But these tests are still infinitely far from changes. While most manufacturers are more willing to change their products than their methods of production, we use exactly the opposite method.

We have made a number of significant changes to our production methods. There is never stagnation here. It seems to me that since we built our first car on the current model, none of the previous devices have remained unchanged. This is the reason why our production is cheap. Those small changes that have been introduced in our cars are aimed at improving driving comfort or increasing power. The materials used in production change, of course, too, as we learn to understand the materials.

In the same way, we want to protect ourselves from production hiccups or from having to increase prices due to possible shortages of any particular material. In these types we have replacement material for almost all parts. For example, of all the steel grades, vanadium is the most popular in our country. The greatest strength is combined with minimal weight; but we would be nothing but bad businessmen if we made our entire future dependent on the ability to obtain vanadium steel. That's why we found a metal to replace it. All varieties of our steel are completely unique, but for each individual grade we have at least one replacement, or even several, and all have been tried and all turned out to be suitable. The same can be said for all varieties of our materials, as well as for all individual parts. At first we made only a few parts ourselves, and did not make motors at all. Nowadays we make the motors ourselves, as well as almost all the parts, because it costs less. We also do this so that we are not affected by market crises and so that foreign manufacturers do not paralyze us with their inability to deliver what we need. During the war, glass prices rose to dizzying heights. We were in the forefront of consumers. We have now started building our own glass factory. If we had spent all our energy on changes in the factory, we would not have gotten far, but since we did not make any changes in the factory, we had the opportunity to concentrate all our efforts on improving manufacturing techniques.

The most important part of a chisel is the tip. Our enterprise is primarily based on this idea. In a chisel, not so much depends on the fineness of the workmanship or the quality of the steel and the quality of the forging; if it does not have an edge, then it is not a chisel, but just a piece of metal. In other words, it is the actual benefit that is important, not the imaginary benefit. What's the point of hitting with a dull chisel with enormous effort if a light blow with a sharp chisel does the same job? The chisel exists to cut, not to pound. Impacts are only a passing phenomenon. So, if we want to work, why not focus our will on the work and get it done in the shortest possible way? The cutting edge in industrial life is the line along which the product of production comes into contact with the consumer. A poor quality product is a product with a dull edge. It takes a lot of extra force to push it through. The spearheads in a factory enterprise are man and machine, working together to do the work. If the person is not suitable, then the machine will not be able to do the job correctly and vice versa. To require more force to be expended on any given work than is absolutely necessary is to be wasteful.

So, the essence of my idea is that wastefulness and greed inhibit true productivity. But wastefulness and greed are not necessary evils. Wastefulness stems mostly from an insufficiently conscious attitude towards our actions or from careless execution of them. Greed is a kind of myopia. My goal was to produce with a minimum expenditure of material and manpower and sell with a minimum profit, and in relation to the total profit, I relied on the size of sales. Likewise, my goal in the process of such production is to pay maximum wages, in other words, to provide maximum purchasing power. And since this method also leads to minimal costs, and since we sell with a minimal profit, we are able to bring our product into line with purchasing power. The enterprise we founded is truly beneficial. And that’s why I want to talk about him. The basic principles of our production are:

1. Don't be afraid of the future and don't be respectful of the past. He who is afraid of the future, that is, of failures, limits the range of his activities. Failures only give you a reason to start again and smarter. Honest failure is not disgraceful; the fear of failure is shameful. The past is useful only in the sense that it shows us the ways and means to development.

2. Ignore the competition. Let the one who does the job better work. An attempt to upset someone's affairs is a crime, because it means an attempt to upset the life of another person in pursuit of profit and to establish the rule of force in place of common sense.

3. Put work for the common good above profit. Without profit, no business can survive. But there is nothing inherently wrong with profit. A well-run enterprise, while bringing great benefits, should and will bring great income. But profitability should result from useful work, and not lie at its basis.

4. Producing does not mean buying cheap and selling high. It means, rather, buying raw materials at reasonable prices and converting them, at as little extra cost as possible, into a good product, which is then distributed to consumers. To gamble, speculate and act dishonestly means complicating only this process.

Subsequent chapters will show how all this came about, what results it led to, and what its significance was for society as a whole.

The beginnings of the business

On May 31, 1921, the Ford Automobile Society produced car No. 5,000,000. It now stands in my museum, next to the small gasoline cart with which I began my experiments and which first ran in the spring of 1893 to my great pleasure. I rode her just as the buntings arrived in Dearborn, and they always return on April 2nd. The two carriages are completely different in appearance and almost equally dissimilar in structure and material. Only the diagram, strangely enough, has hardly changed except for some of the flourishes that we have thrown away in our modern car. That little old cart, in spite of its two cylinders, ran twenty miles an hour, and with its tank of only twelve liters lasted a full sixty miles. And now she is the same as on the first day. The design developed much less quickly than structural engineering and materials application. Of course, she too has improved; the modern Ford - the Model T - has four cylinders, an automatic starting device and, in general, is in all respects a more convenient and practical vehicle. It is simpler than its predecessor, but almost every part of it was already included in the original model. The changes resulted from our experiments in design, not from a new principle, and from this I learn the important lesson that it is better to put all our efforts into improving a good idea instead of chasing other, new ideas. A good idea gives you exactly as much as you can handle at once.

Life as a farmer forced me to invent new and better means of transportation. I was born July 30, 1863, on a farm near Dearborn, Michigan, and my first impression that I can remember is that there was too much labor in relation to the results. And now I still have similar feelings about farm life.

There is a legend that my parents were very poor and had a hard time. True, they were not rich, but real poverty was out of the question. For Michigan farmers, they were even prosperous. My home is still intact and, together with the farm, is part of my possessions.

On ours, as on other farms, we had to do too much heavy manual labor back then. From my early youth I thought that many things could be done differently, in some better way. That’s why I turned to technology, and my mother always claimed that I was a born technician. I had a workshop with all sorts of metal parts instead of tools before I could call anything my own. At that time there were no newfangled toys; everything we had was homemade. My toys were tools, just as they are now. Every piece of the car was a treasure for me.

The most important event of my childhood was my encounter with a locomobile, about eight miles from Detroit, when we were driving into the city one day. I was twelve years old then. The second most important event, which occurred in the same year, was the watch given to me.

I picture that car like it was yesterday; it was the first cart without a horse that I saw in my life. It was mainly designed to drive threshing and sawmills and consisted of a primitive moving machine with a boiler; At the back were a vat of water and a box of coal. True, I have already seen many locomobiles transported on horses, but this one had a connecting chain leading to the rear wheels of a cart-like stand on which the boiler was placed. The machine was placed over the boiler, and a single person on a platform at the back of the boiler could shovel the coals and operate the valve and lever. This machine was built by Nichols-Shepard and Co. in Battle Creek. I immediately found out about this. The car was stopped to let us and the horses through, and I, sitting behind the cart, entered into a conversation with the driver before my father, who was driving, saw what was happening. The driver was very glad that he could explain everything to me, as he was proud of his car. He showed me how to remove the chain from the driving wheel and how to put on a small drive belt to drive other cars. He told me that the machine made two hundred revolutions per minute and that the connecting chain could be released to stop the locomobile without stopping the action of the machine. The latter device, although in a modified form, is found in our modern car. It is not important in steam engines, which are easy to stop and start again, but it is even more important in motors.

This locomobile was the reason I became immersed in automotive technology. I tried to build models, and several years later I managed to make one that was quite suitable. From the time I, as a twelve-year-old boy, met the locomobile until today, the whole force of my interest has been directed towards the problem of creating an automatically moving machine.

When I went to the city, my pockets were always filled with all sorts of rubbish: nuts and pieces of iron. Often I managed to get my hands on a broken watch and tried to repair it. When I was thirteen, I managed to fix my watch for the first time so that it ran correctly. From the age of fifteen I could repair almost any clock, although my tools were very primitive. Such fuss is terribly valuable. You can't learn anything practical from books - a machine is to a technician what books are to a writer, and a real technician would, in fact, have to know how everything is made. From there he will get ideas and since he has a head on his shoulders, he will try to apply them.

I could never be particularly interested in farm work. I wanted to deal with cars. My father was not very sympathetic to my passion for mechanics. He wanted me to become a farmer. When I left school at the age of seventeen and entered the Drydock machine shop as an apprentice, I was considered almost dead. My apprenticeship was easy and without difficulty - I had mastered all the knowledge necessary for a machinist long before the end of my three-year apprenticeship, and since, in addition, I also had a love for fine mechanics and a special passion for watches, I worked at night in the repair shop of a jeweler. At one time, in those young years, I had, if I’m not mistaken, more than 300 hours. I figured that I could already make a decent watch for about 30 cents, and I wanted to get into this business. However, I left it, proving to myself that watches, in general, do not belong to the absolutely necessary items in life and that therefore not all people will buy them. How I came to this amazing conclusion, I don’t remember well. I hated the ordinary work of a jeweler and watchmaker, except when it presented particularly difficult tasks. Even then I wanted to make some product for mass consumption. Around that time, general time for railway traffic was introduced in America. Until then, they were guided by the sun, and for a long time railway time was different from local time, as it is now, after the introduction of summer time. I racked my brain a lot and managed to make a watch that showed both times. They had a double dial and were considered a kind of landmark throughout the area.

In 1879—almost four years after my first encounter with the Nichols-Shepard locomobile—I obtained the opportunity to drive a locomobile, and when my apprenticeship ended, I began working with the local representative of the Westinghouse Company as an expert in the assembly and repair of their locomobiles. Their machine was very similar to Shepard's, except that here the machine was placed in the front and the boiler in the back, with power transferred to the rear wheels using a drive belt. The cars were made in an hour up to twelve miles, although the speed of movement played a secondary role in the design. Sometimes they were also used for heavy loads, and if the owner happened to be working with threshing machines at the same time, he simply tied his threshing machine and other equipment to the locomobile and drove from farm to farm. I thought about the weight and cost of locomobiles. They weighed many tons and were so expensive that only a large landowner could purchase them. Often their owners were people who engaged in threshing as a profession, or sawmill owners and other manufacturers who needed transport engines.

Even earlier, I had come up with the idea of building a light steam cart that could replace horse traction, mainly as a tractor for extremely heavy arable work. At the same time, the thought occurred to me, as I now vaguely remember, that exactly the same principle could be applied to carriages and other means of transportation. The idea of a horseless carriage was extremely popular. For many years, in fact since the invention of the steam engine, there had been talk about a carriage without horses, but at first the idea of a carriage seemed to me not as practical as the idea of a machine for difficult rural work, and of all rural work, plowing was the most difficult. Our roads were bad and we were not used to driving around much. One of the greatest achievements of the automobile is the beneficial effect it has had on the farmer's outlook—it has broadened it greatly. It goes without saying that we did not go to the city unless there was some important business there, and even then we went no more than once a week. In bad weather, sometimes even less often.

As an experienced machinist with a tolerable workshop at his disposal on the farm, it was not difficult for me to build a steam cart or tractor. At the same time, the idea came to me to use it as a means of transportation. I was firmly convinced that it was not profitable to keep horses, considering the labor and expense of keeping them. Therefore, it was necessary to invent and build a steam engine that was light enough to pull an ordinary cart or plow. The tractor seemed most important to me. To transfer the difficult, harsh work of the farmer from human shoulders to steel and iron has always been the main object of my ambition. Circumstances are to blame for the fact that I first turned to the production of crews themselves. I found, in the end, that people were more interested in a machine in which they could drive on country roads than in a tool for field work. I even doubt that the light field tractor could have taken root at all if the automobile had not gradually but surely opened the eyes of the farmer. But I'm getting ahead of myself. Back then I thought that a farmer would be more interested in a tractor.

I built a steam-powered cart. It was functioning. The boiler was heated with oil; the power of the engine was great, and the control by means of the shut-off valve was simple, orderly and reliable. But the cauldron contained danger. In order to achieve the required force, without unduly increasing the weight and displacement of the engine, the machine had to be under high pressure. Meanwhile, it is not particularly pleasant to sit on a boiler under high pressure. In order to secure it at least to some extent, it was necessary to increase the weight so much that this again destroyed the gain acquired by high pressure. For two years I continued my experiments with various systems of boilers - power and control presented no difficulty - and in the end I abandoned the idea of a road cart driven by steam. I knew that the British used steam carriages on their rural roads, which were real locomotives and had to pull entire convoys. It was not difficult to build a heavy steam tractor suitable for a large farm. But we don't have English roads. Our roads would destroy any large and strong steam tractor. And it seemed to me that it was not worth building a heavy tractor; only a few wealthy farmers could buy it.

But I didn’t give up on the idea of a horseless carriage. My work with the Westinghouse representative strengthened my conviction that the steam engine was unsuitable for a light crew. Therefore, I remained in their service for only one year. Heavy steam engines and tractors could no longer teach me anything, and I did not want to waste time on work that would lead nowhere. A few years earlier, during my apprenticeship, I read in an English magazine about a “silent gas engine,” which had just appeared in England at that time. I think it was Otto's engine. It was powered by illuminating gas and had one large cylinder; the transmission was therefore uneven and required an unusually heavy flywheel. As for weight, it produced much less work per pound of metal than a steam engine, and this seemed to make the use of illuminating gas for crews altogether impossible. I became interested in the engine only as a machine in general. I followed its development through English and American magazines that came into our workshop, especially every indication of the possibility of replacing illuminating gas with gas obtained from gasoline vapor. The idea of a gas engine was by no means new, but this was the first serious attempt to bring it to market. It was greeted with more curiosity than enthusiasm, and I do not remember a single person who believed that the internal combustion engine could be further widespread. All smart people irrefutably proved that such a motor cannot compete with a steam engine. They had no idea that he would ever conquer the field. All smart people are like that, they are so smart and experienced, they know exactly why this and that cannot be done, they see the limits and obstacles. That's why I never hire a purebred specialist. If I wanted to kill my competitors by dishonest means, I would provide them with hordes of specialists. Having received a lot of good advice, my competitors could not get started.

I was interested in the gas engine and followed its development. But I did this purely out of curiosity until about 1885 or 1886, when I gave up the steam engine as an engine for a cart I wanted to build one day, and had to look for a new motive power. In 1885 I repaired Otto's engine at Eagle Repair Shops in Detroit. There was no one in the whole city who knew much about this. They said I could do it, and although I had never worked with Otto engines before, I took the job and did it happily. So I had the opportunity to study the new engine first hand and in 1887 I built myself a model based on the four-stroke model I had, just to make sure that I understood the principle correctly. A “four-stroke” engine is one where the piston must pass through the cylinder four times to produce power. The first stroke takes in gas, the second compresses it, the third causes it to explode, and the fourth pushes out excess gas. The small model worked very well; it had a one-inch bore and three-inch stroke, ran on gasoline, and although it produced little power, was relatively lighter than any machine on the market. I subsequently gave it to a young man who wanted to receive it for some purpose, and whose name I have forgotten. The engine was disassembled, it became the starting point for my further work with internal combustion engines.

At that time I was again living on a farm, where I returned not so much to become a farmer as to continue my experiments. As a learned mechanic, I have now set up a first-class workshop instead of the doll workshop of my childhood years. My father offered me 40 acres of forest if I would give up my cars. I agreed temporarily because my job gave me the opportunity to get married. I set up a sawmill for myself, stocked up on a transport engine and began cutting and sawing trees in the forest. Some of the first boards and beams went into the house on our new farm. This was at the very beginning of our married life. The house was not large, only thirty-one square feet, one and a half stories high, but it was cozy. I built a workshop nearby and, when I was not busy cutting down trees, I worked on gas engines, studying their properties and functions. I read everything I could get my hands on, but most of all I learned from my own work. A gas engine is a mysterious thing; it doesn’t always work as it should. Just imagine how these first models behaved.

In 1890 I first began working with two cylinders. The single-cylinder engine was completely unsuitable for transport purposes - the flywheel was too heavy. After completing the work on the first four-stroke engine of the Otto type, and even before I ventured to take up the two-cylinder engine, I made a whole series of machines from iron tubes for experimental purposes. I had, therefore, a fair amount of experience. I was of the opinion that a motor with two cylinders could be used for transportation purposes, and initially had the idea of applying it to a bicycle in direct connection with a connecting rod, with the rear wheel of the bicycle serving as a flywheel. The speed had to be controlled solely by the valve. However, I never carried out this plan, since it very soon became clear that the motor with reservoir and other accessories was too heavy for a bicycle. Two mutually complementary cylinders had the advantage that at the moment of explosion in one cylinder, burnt gases were pushed out in the other. This reduced the weight of the flywheel required for regulation. The work began in my workshop on the farm. Soon afterwards I was offered a position as an engineer and mechanic with the Detroit Electric Company at a monthly salary of forty-five dollars. I accepted it because it gave me more than the farm, and even without that I decided to give up farming. The trees were all cut down. We rented a house in Detroit on Bagley Avenue. The workshop moved with me and opened in a brick barn behind the house. For many months I worked at the Electric Company on the night shift - I had very little time for my work; after that I switched to the day shift and worked every evening and all night on Sunday on the new engine. I can't even say that the work was hard. Nothing that really interests us is difficult for us. I was confident of success. Success will certainly come if you work hard. However, it was terribly valuable that my wife believed in him even more strongly than I did. She has always been like this.

I had to start with the basics. Although I knew that a number of people were working on a carriage without a horse, I could not find out any details about it. The biggest challenges for me were getting the spark and the weight issue. My experience with steam tractors helped me in the transmission, handling and general aspects. In 1892 I made the first automobile, but had to wait until the following spring until it ran to my great satisfaction. My first carriage was somewhat similar in appearance to a peasant's cart. It had two 2 1/2-inch diameter cylinders with a six-inch stroke, placed side by side above the rear axle. I made them from the exhaust pipe of a steam engine I purchased. They developed about four horsepower. The power was transmitted from the engine via a belt to the drive shaft and from the latter, via a chain, to the rear wheel. The cart could seat two people, with the seat mounted on two posts and the body resting on elliptical springs. The machine had two strokes - one at ten, the other at twenty miles per hour, which were achieved by moving the belt. A lever with a handle placed in front of the counselor’s seat served for this purpose. Pushing it forward, they reached a fast speed, back - a quiet one; in a vertical position the speed was idle. To start the car, you had to turn the handle by hand, leaving the engine idling. To stop, you just had to release the lever and press the foot brake. There was no reverse gear, and speeds other than the two indicated were achieved by regulating the gas flow. I bought the iron parts for the cart frame, as well as the seat and springs. The wheels were bicycle wheels, twenty-eight inches wide, with rubber tires. I cast the steering wheel according to a mold I prepared myself, and I also designed all the finer parts of the mechanism myself. But very soon it turned out that there was still not enough regulating mechanism to evenly distribute the available force during curvilinear movement between both rear wheels. The entire crew weighed about five hundred pounds. Under the seat there was a tank that held 12 liters of gasoline, which fed the engine through a small tube and valve. Ignition was achieved by an electric spark. The motor was originally air-cooled, or, more precisely, had no cooling at all. I found that it became hot after an hour or two of driving, and very soon placed a vessel of water around the cylinder, connecting it by a tube to a reservoir located behind the carriage.

I came up with all these details in advance with a few exceptions. This is what I have always done in my work. I first draw a plan in which every detail is worked out to completion before I begin to build. Otherwise, a lot of material is lost during work on various additional devices, and in the end the individual parts turn out to be incompatible with each other. Many inventors fail because they fail to distinguish between planning and experimentation. The main difficulties during construction were obtaining appropriate material. Then the question of tools arose. There were still various changes and adjustments to be made in the details, but what delayed me most was the lack of money and time to purchase the best materials for each individual part. However, in the spring of 1893 the machine had advanced so far that it could be put into operation, to my great satisfaction, and I had the opportunity to test the design and material on our country roads.

The real business begins

In a small brick barn, at No. 81 Park Square, I had ample opportunity to develop a plan and method for the production of a new automobile. But even when I managed to create an organization quite to my taste - to create an enterprise that put the good quality of products and the satisfaction of the public as the main principle of its activity, even then I clearly saw that as long as puzzling production methods remained in force, it was unthinkable to create a first-class and justifiable the cost of the car.

Everyone knows that the same thing works better the second time than the first time. I don't know why the industry of that time did not take this basic principle into account. Manufacturers seemed to be in a hurry to release goods to the market and did not have time to properly prepare. Working “to order” instead of producing products in series is obviously a habit, a tradition inherited from the period of handicraft production. Ask a hundred people in what form they would like to perform such and such a subject. Eighty of them will not be able to answer and will leave the resolution of the question to the discretion of the manufacturer. Fifteen people will feel obliged to say something, and only five people will express a rationale and a sensible wish and demand. The first ninety-five people, who are made up of those who do not understand anything and admit it and those who also do not understand anything, but do not want to admit it - this is the real contingent of buyers of your product. Five people with special requirements are either able to pay for a special order or not. In the first case, they will be buyers, but their number is extremely limited. Out of ninety-five people, there are only ten or fifteen who are willing to pay more for better quality, while the rest pay attention only to the price, without regard to dignity. True, their number is gradually decreasing. Buyers begin to internalize the skill of buying. Most begin to pay attention to dignity and strive to get the best possible quality for every extra dollar. Thus, if we study which product best suits the needs and tastes of this 95%, and develop production methods that will bring a good quality product to market at the lowest price, the demand will be so great that it can be considered universal.

I don't mean normalization (standardization). The term "normalization" may cause confusion, since it implies a certain inflexibility of production and design, and the manufacturer ultimately settles on that type of product that sells most easily and profitably.

End of free trial.

Current page: 1 (book has 16 pages total) [available reading passage: 11 pages]

Henry Ford

Henry Ford. My life, my achievements

Introduction

My guiding idea

Our country has just begun to develop; no matter what they say about our amazing successes, we barely plowed the top cover. Despite this, our successes were quite amazing. But if we compare what has been done with what remains to be done, all our successes turn into nothing. One has only to remember that more force is expended to plow the land than in all the industrial enterprises of the country combined - and one immediately gets an idea of the possibilities that lie before us. And precisely now, when so many states are experiencing a process of fermentation, now, with anxiety reigning everywhere, the moment has apparently come when it is appropriate to recall something from the area of the upcoming tasks in the light of the problems that have already been resolved.

When one starts talking about the increasing power of machines and industry, we easily see an image of a cold, metallic world in which trees, flowers, birds, meadows are crowded out by the grandiose factories of a world consisting of iron machines and human machines. I do not share this idea. Moreover, I believe that unless we learn to use machines better, we will not have time to enjoy trees and birds, flowers and meadows.